What is Mimikatz and why it’s a security risk

Although it was originally created for research purposes, Mimikatz has found widespread application as a tool in post-compromise intrusions. In the wrong hands, it could help attackers leverage their way to broader domain access.

This article explains what Mimikatz is exactly, how it works, and how security teams can spot and mitigate risks from an attack involving Mimikatz.

Note: Using Mimikatz for malicious purposes is illegal and unethical. This article is for educational and defensive purposes only.

What is Mimikatz?

Mimikatz is an open-source post-exploitation tool that extracts authentication data from memory on Windows machines. The tool was developed in 2007 by security researcher Benjamin Delpy, who wanted to demonstrate a key issue: even though Windows protects passwords in many ways, some authentication secrets can still be recovered from system memory under the right conditions.

At the time, many organizations assumed that once a user logged in, their credentials were “safe.” Mimikatz helped prove that access to one machine could potentially lead to access to many others, especially in enterprise environments.

Since then, operating system defenses and security tools have evolved to limit how and when credentials are exposed in memory, reducing the impact of these techniques in many modern systems.

Despite these mitigations, Mimikatz remains a commonly abused post-exploitation tool. In real-world intrusions, attackers may use it after establishing initial access to enable privilege escalation and lateral movement.

Legitimate security research vs. malicious use

Mimikatz is still a dual-use tool in cybersecurity. Many security professionals use Mimikatz in controlled environments to evaluate defenses and simulate attacker behavior.

Penetration testers and red teams incorporate it into exercises intended to reveal gaps in authentication protections and help organizations understand how an attacker might move once they gain access. Red teams operate under authorization to mimic real intrusions so that defenders can improve detection, response, and mitigation.

At the same time, defenders and blue teams study Mimikatz because it represents a common credential theft technique. Understanding how it interacts with Windows authentication and memory helps defenders calibrate protections and attack surface reduction rules to prevent credential dumping.

Mimikatz is also widely observed in real intrusions as part of post-compromise activity, where attackers dump credentials to support lateral movement, privilege escalation, and wider access across a network.

When Mimikatz is typically used in attacks

Mimikatz is typically used after initial compromise. In most cases, the initial foothold is low-privilege, and Mimikatz is only used after the attacker has obtained administrative privileges, since those are typically required to access credential material in memory.

At that point, Mimikatz is used to harvest data that supports the next phase of the intrusion, accessing additional endpoints, then servers, and potentially the domain infrastructure.

How Mimikatz works

Mimikatz works by taking authentication secrets that Windows temporarily stores for normal operation and making them readable. Windows needs this information to support seamless access to local resources, network shares, and domain services without constantly re-prompting users to log in.

When an attacker has sufficient privileges, Mimikatz can access those protected areas, locate the stored authentication material, and extract it. The attacker can then reuse what was extracted to authenticate as that user.

The flow is:

- A user logs into Windows.

- Windows stores authentication artifacts to maintain the session.

- Mimikatz locates and extracts those artifacts from protected storage.

- The extracted material can be reused to authenticate as the same user.

Credential storage in Windows

To understand what Mimikatz is extracting, it helps to understand what Windows stores after authentication, and why. Windows stores authentication data in different forms depending on the protocol and context. These values support normal session behavior, but if an attacker gains access to either, they can reuse them as proof of identity where accepted.

In a domain environment, authentication is typically based on Kerberos, where Windows relies on ticket-based access. That means a user doesn’t repeatedly send a password (or password-derived secret) to every service they access.

Instead, after the initial login, the user receives a set of cryptographic “tickets” that prove they’ve already been authenticated. Those tickets are then presented to access resources like file shares, internal applications, and domain services.

In other cases, Windows may fall back to New Technology LAN Manager (NTLM), which uses password-derived values to prove identity. When a user attempts to access a resource, the server sends a random challenge. The client then uses the NTLM hash to generate a challenge-response and returns it to the server. The server validates the response and, if it matches what it expects, grants access.

The role of the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) process

LSASS is where much of that authentication data lives while a user is logged in. It’s a critical Windows process responsible for handling authentication and enforcing security policies.

When a user signs in, LSASS tracks that session and loads the authentication providers Windows relies on, such as NTLM and Kerberos. To keep the user authenticated across the system and network, LSASS also retains credential-related data in memory, such as hashes, tickets, and session keys, and issues access tokens that represent the user’s identity and privileges.

Mimikatz works by extracting this information directly from LSASS memory. It enumerates active logon sessions, identifies the credential structures associated with those sessions, and pulls the authentication material stored inside them. This is why Mimikatz typically requires elevated privileges: LSASS memory is protected because it contains the secrets Windows uses to prove identity.

Accessing passwords, hashes, and tickets

Once Mimikatz has access to the right memory structures, the final piece is what it can actually recover from them. When Mimikatz runs with the necessary permissions, it can extract several types of credential material depending on the Windows version, system configuration, and authentication methods in use. Common examples include:

- Passwords (in some cases): Plaintext credentials may be recoverable in environments where legacy authentication support or insecure settings allow them to be stored in memory.

- NTLM hashes: Password-derived values associated with NTLM authentication. While they aren’t the original password, they can still function as proof of identity in certain authentication flows.

- Kerberos tickets: Ticket data tied to Active Directory (AD) authentication, including tickets used to access specific services and maintain domain session continuity.

This is what makes Mimikatz a high-impact post-exploitation tool: it extracts authentication artifacts that are already valid within the environment, enabling attackers to extend access beyond the initially compromised system.

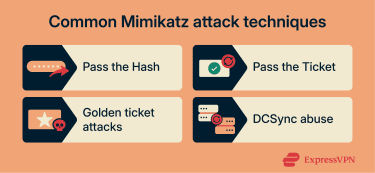

Common Mimikatz attack techniques

After extracting authentication artifacts from a compromised system, attackers can reuse them to impersonate users, move laterally, and escalate privileges inside a Windows domain.

The techniques below represent some of the most common ways Mimikatz is used during post-compromise activity, especially in AD environments (Windows networks where a central system called a Domain Controller (DC) manages identities, access, and authentication for an organization).

Pass the Hash

Pass the Hash is a technique where an attacker authenticates using a password hash instead of the user’s actual plaintext password. Since some Windows authentication flows accept the hash as proof of identity, an attacker who obtains it may be able to access other systems or services without ever cracking the password.

This technique is especially effective in environments where NTLM is still widely used and where the same local administrator credentials exist across multiple machines.

Pass the Ticket

Pass the Ticket is a Kerberos-based technique where an attacker reuses a stolen Kerberos ticket to authenticate to services as the victim user. Because Kerberos relies on tickets to grant access, a valid ticket can function as a reusable authentication artifact within its allowed scope and lifetime. There are two kinds of tickets within the Kerberos system:

- Ticket-granting ticket (TGT): Controlled by a DC’s Key Distribution Center (KDC) and proves that a particular user is authenticated to a domain.

- Ticket-granting service (TGS): Tickets that allow access to certain resources (files, applications, or databases) within a domain.

Mimikatz is able to extract and reuse these cryptographically signed tickets directly from the Windows memory, and since Windows already trusts them, attackers may gain system access.

Golden ticket attacks

A golden ticket attack involves forging a Kerberos TGT, which is the “master ticket” a user receives after they first authenticate to AD. A valid TGT allows a user to request additional service tickets and access resources across the domain without re-entering credentials.

This becomes possible if an attacker obtains the secret tied to the Kerberos TGT (KRBTGT) account. KRBTGT is a built-in AD account that acts as the domain’s Kerberos signing identity. Its secret is used to cryptographically sign and validate Kerberos tickets so DCs can trust them.

With that secret and a domain-level compromise, an attacker can generate a forged TGT that AD will accept as legitimate. This can enable long-lasting or highly privileged access, and it can remain effective even if individual user passwords are changed.

DCSync abuse

In a traditional Windows domain, DCs are regularly required to sync password and user data between them, which can only be requested by privileged accounts such as domain admins or DCs with replication rights.

If an attacker gains that level of privilege, tools like Mimikatz can abuse this replication process by impersonating a DC and requesting the replicated credential data from a real DC. This allows the attacker to obtain sensitive information such as NTLM password hashes and Kerberos keys without dumping LSASS on a workstation, because the data is retrieved directly from AD replication instead.

This is different from local credential dumping, where an attacker extracts local account password hashes from a single compromised machine, for example, from the Security Account Manager (SAM) database. DCSync instead pulls domain credential data directly from a DC using replication permissions.

Why Mimikatz is dangerous

Mimikatz is dangerous because it targets the part of a Windows environment that everything else depends on: authentication. Once credentials are exposed, attackers don’t need to exploit every system individually, as they can reuse stolen authentication material to access other machines, services, and accounts as if they were legitimate users.

In practice, Mimikatz often acts as the bridge between one compromised endpoint and broader access across the environment.

Lateral movement

Mimikatz directly supports lateral movement because the artifacts it extracts, especially NTLM hashes and Kerberos tickets, can be used to authenticate to other systems.

Instead of exploiting a second machine, an attacker can often extract authentication material from one host using Mimikatz, reuse it to log into another host as the same user, and repeat the process until higher-value systems are reached.

Privilege escalation risks

Mimikatz increases privilege escalation risk because, once an attacker has administrative-level access on a Windows system, it can extract credential material from the LSASS process. If a privileged account (like a local admin or domain admin) has logged into that machine, LSASS may contain authentication material tied to that session.

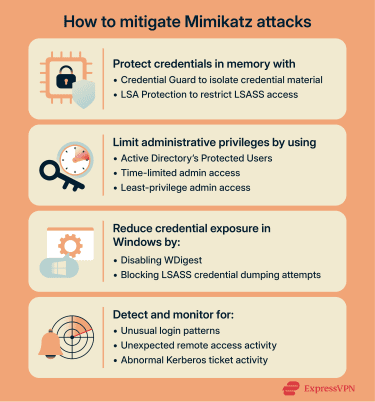

How Mimikatz attacks are mitigated

There are several practical ways security teams can reduce the likelihood and impact of a Mimikatz attack.

Protecting credentials in memory

Mimikatz attacks rely on its ability to interact with the LSASS memory, where authentication artifacts are stored. However, there are ways to protect these credentials within the memory itself.

Credential Guard

Credential Guard is a built-in Windows security feature that uses virtualization-based security (VBS) to isolate credential material from the rest of the operating system. Normally, LSASS runs in the same OS context as other processes, which increases the risk of credential dumping once an attacker gains elevated access.

With Credential Guard enabled, LSASS credential material is isolated so that NTLM hashes and Kerberos secrets are significantly harder to extract, even after compromise. This is especially valuable on systems where privileged users log in, such as admin workstations and jump hosts.

LSA Protection

Local Security Authority (LSA) Protection is a Windows security feature that runs LSA as a Protected Process Light (PPL). This makes it harder for untrusted processes to read or inject into LSASS, because only trusted, properly signed code is allowed to interact with it.

In practice, LSA Protection reduces credential dumping risk by blocking common attempts to access LSASS memory and limiting unauthorized process interaction with authentication components.

Limiting administrative privileges

Mimikatz becomes far more dangerous when it’s run on systems where privileged users are logged in or where admin credentials are widely reused. Reducing administrative privilege, both in scope and in exposure, limits what an attacker can steal and reuse. Here are practical ways to control admin risk in a domain environment:

Use of privileged accounts

High-value accounts, such as those with administrative privileges, can be added to the Protected Users group in AD to help reduce the scope and impact of a Mimikatz attack. When a protected user signs in to a system, it prevents the workstation from caching NTLM hashes and forces Kerberos-based authentication.

Unlike traditional Kerberos tickets, privileged users’ tickets have a shorter lifespan, which translates into a smaller exploit window for an attacker. Plus, these tickets are encrypted, so they’re harder to crack or replay in post-compromise scenarios.

Using just-in-time models

Using just-in-time (JIT) and just-enough-administration (JEA) privilege models in high-risk environments can help mitigate the impact of a Mimikatz attack. Instead of providing system-wide privileges to a user, JIT and JEA models only provide access for a limited time or for a specific purpose.

Beyond that, the privileges are automatically revoked. Even if an attacker scrapes these credentials from system memory, they may not be usable at all, reducing the scope of lateral movement.

Reducing credential exposure in Windows

Windows includes built-in settings and security controls that can reduce how much reusable credential material is available on endpoints. This makes credential dumping harder and lowers the payoff for attackers.

Disable legacy protocols

Legacy components like WDigest can expose plaintext credentials in memory under certain conditions. While WDigest is disabled by default on modern Windows versions, older systems or legacy configurations may still enable it.

If WDigest isn’t required for compatibility, disabling it reduces the chance of plaintext credential exposure and limits what an attacker can recover from memory.

Attack surface reduction (ASR) rules

ASR rules are policy-based controls in Microsoft Defender that can block behaviors associated with credential dumping, including suspicious attempts to access LSASS.

Because Mimikatz depends on interacting with sensitive authentication memory and related processes, ASR rules can disrupt credential theft early, in some cases, before hashes or tickets are successfully extracted.

Detection and monitoring controls

Even strong preventive controls can fail, so detection matters. Monitoring should focus on the behaviors that typically follow credential dumping and reuse. Common indicators include:

- Unusual login patterns, such as logins at odd hours or rapid authentication across multiple machines

- New or unexpected use of remote administration protocols like Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) or PowerShell Remoting

- Kerberos tickets appearing on unusual hosts or with abnormal lifetimes, which may suggest ticket abuse or privilege escalation

FAQ: Common questions about Mimikatz security

Is Mimikatz malware?

No. Mimikatz is a legitimate post-exploitation tool originally created for security research and still used in authorized testing. However, attackers also use it to extract credential material from Windows memory to support lateral movement and privilege escalation.

What is Mimikatz used for?

Mimikatz is used to extract Windows authentication artifacts from memory, including NTLM hashes, Kerberos tickets, and other credential-related session data. Security teams use it in controlled testing and incident response to measure credential exposure and validate defenses. Attackers use it after compromise to steal reusable authentication material and expand access through lateral movement and privilege escalation.

Can Mimikatz be detected?

One way Mimikatz can be detected is by monitoring the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) memory for any unauthorized access by non-system processes or unsigned binaries. Other methods include monitoring abnormal login activities, sudden access to privileged systems, and Kerberos ticket anomalies such as abnormal lifetimes.

Is using Mimikatz illegal?

The legality of using Mimikatz depends on the user's intent and purpose. Security researchers use Mimikatz for penetration testing, research, academic training, and internal security validation. All of these are legitimate uses of the tool. However, malicious actors can use the tool to break into systems for credential harvesting, escalating privileges, or possibly gaining unauthorized domain-level access, all of which are illegal.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN