What is a buffer overflow, and why is it dangerous?

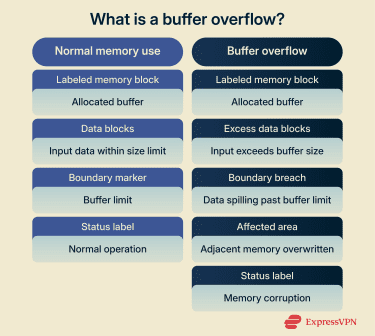

A buffer overflow occurs when a program writes more data to a fixed-size memory buffer than it was designed to hold, causing the excess data to spill into adjacent memory.

Programs need memory to store data while they run. A server may have 32GB of RAM, but individual programs don’t get unlimited space. Instead, they rely on smaller, fixed memory areas to temporarily hold data. When too much information is pushed into one of those areas, it can overflow into places it doesn’t belong.

That’s where buffer overflow issues begin. In this article, we’ll explore why buffer overflows can cause security vulnerabilities, what can happen if they’re exploited, and how developers and security teams can reduce their impact.

What is a buffer overflow?

A buffer is a small, fixed area of memory that programs use to temporarily store data, such as user input or instructions being processed. It has a defined size, and it’s meant to hold only a certain quantity of information.

A buffer overflow happens when a program tries to store more data in a memory buffer than it was designed to hold. Instead of stopping at the buffer’s limit, the excess data spills into nearby memory and overwrites information that was never meant to change. A simple way to think about it is pouring water into a glass. Once the glass is full, the extra water spills over and gets everything wet.

Overflow usually happens when applications don’t check how much input they receive or assume the data will always fit. When those assumptions are incorrect, the boundaries of memory are also compromised.

Buffer overflows have been a known security problem for decades. One of the earliest cyberattacks was the Morris Worm in 1988. It exploited a buffer overflow vulnerability to spread automatically across early internet-connected systems. The worm took advantage of improper memory handling in network services to cause systems to crash or become unusable.

This demonstrated how a single buffer overflow vulnerability could disrupt large numbers of machines and helped establish memory safety as a foundational concern in software security.

What happens during a buffer overflow attack

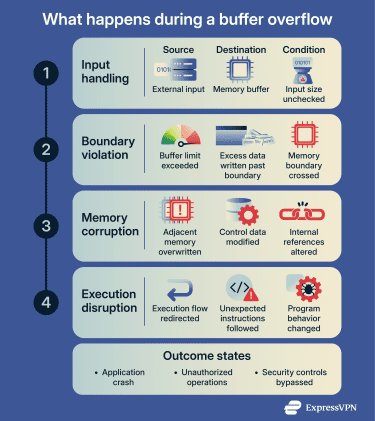

Attackers can use malicious files or specially crafted input that intentionally triggers a buffer overflow as part of a cyberattack. This can force data into memory areas that sit beyond the buffer’s boundaries.

As a result, the data stored next to the buffer can be overwritten or manipulated. If those memory locations influence how the program operates, the application’s normal execution path may change, and it can cause the system to crash.

That being said, a successful buffer overflow attack can cause far more damage than simply crashing an app or system. It introduces a vulnerability that can result in significant cybersecurity issues, including denial of service (DoS), remote code execution, data corruption or exposure, and granting access to unauthorized personnel.

Once a buffer overflow is triggered, the danger comes from where the excess data ends up in memory, not from the data itself. Overflowing a buffer can overwrite nearby values that the program relies on, corrupting internal references or instructions.

This corruption then alters the program’s normal execution flow, potentially causing crashes, unpredictable behavior, or the execution of operations the application was never designed to perform. If attacker-controlled data is involved, the program may even run malicious code supplied by the attacker.

The effects vary depending on the location of the buffer, the type of memory affected (stack or heap), and how the application manages its execution flow. While some overflows cause immediate failures, others leave the program running in a corrupted state, making the consequences harder to detect and contain.

Common buffer overflow exploitation methods

Attackers can use a vulnerability in different ways, depending on how the affected program handles memory and runs code. Common exploitation approaches include:

- Return address manipulation: Some attacks focus on altering control data in memory so that the program continues execution from an unintended location rather than returning to its original flow.

- Shellcode injection: Attackers introduce small blocks of malicious code, commonly known as shellcode, to trick the compromised application into executing.

- No Operation (NOP) sleds: NOP sleds, also known as ramps, involve sequences of instructions designed to guide execution toward malicious code when precise control over memory locations is difficult.

- Heap spraying: Attackers fill large areas of dynamically allocated memory with data they control, increasing the likelihood that execution will be redirected to unintended locations.

- Return-oriented programming (ROP): ROP attacks reuse existing instruction sequences already present in memory, chaining them together to perform unintended operations without introducing new executable code.

As protections against these attacks improve, exploitation techniques adapt to bypass them, so buffer overflow vulnerabilities are an ongoing security concern.

Types of buffer overflow attacks

Buffer overflow attacks aren’t a single technique but a family of related vulnerabilities, distinguished by where the overflow occurs and what the attacker can influence as a result. Some overflows allow attackers to overwrite control data and hijack execution, while others primarily lead to crashes or data corruption.

Where a buffer lives in memory affects how a failure presents itself and how difficult it is to diagnose.

- Failure timing often differs: Some overflows cause immediate crashes, while others leave the application running in a corrupted state before problems surface later.

- Symptoms may not appear near the root cause: Memory corruption can affect parts of the program that execute much later, making the original overflow harder to trace.

- Stability and security risks vary: Short-lived failures may disrupt execution, while longer-lived corruption can undermine application state or data integrity.

- Containment becomes harder once memory is corrupted: When internal assumptions break, even unrelated code paths may begin behaving unpredictably.

These differences don’t change the underlying vulnerability, but they do affect how visible and controllable the failure is once it occurs.

Stack-based buffer overflow

The stack is a region of memory that stores function call information, local variables, and control data used during program execution. A stack-based buffer overflow occurs when a program writes more data into a buffer located on the stack than it can safely hold.

When a buffer on the stack overflows, excess data can overwrite nearby values stored in the stack frame, including the function’s return address. If the return address is corrupted, the program may crash or continue execution at an unintended location, causing behavior the developer never intended.

These overflows are closely tied to how functions manage memory, which is why they’re often discussed alongside stack-related concepts. Still, the failure comes from exceeding a buffer’s limits, not from the stack itself running out of space.

Stack-based overflow vs. stack overflow: What’s the difference?

The terms “stack overflow” and “stack-based buffer overflow” are similar, but they describe different problems with very different security implications.

A stack overflow usually happens when a program exhausts its available stack space, often due to deep or infinite recursion. It’s a resource exhaustion error, not a memory corruption issue.

A stack-based buffer overflow, by contrast, involves writing too much data into a buffer that happens to live on the stack. The problem isn’t the call stack growing too large: it’s data spilling past its intended boundary and overwriting adjacent memory.

Heap-based buffer overflow

The heap is a region of memory that’s used to dynamically allocate and manage data at runtime, rather than having fixed memory set aside in advance. Errors in how heap memory is allocated, accessed, managed, or freed can result in heap-based vulnerabilities, including memory corruption that may affect program behavior or security. Some of these issues involve writing past buffer boundaries, while others stem from incorrect memory lifecycle handling rather than overflows themselves.

When this happens, the excess data can overwrite nearby memory used by other parts of the program. It can corrupt internal data structures, cause crashes, or leave the application running in an unstable state.

Heap-based overflows are generally much harder to exploit than stack-based overflows. This is because heap memory is more complex and dynamic, often requiring a deep understanding of how a program allocates, uses, and frees memory, as well as careful analysis of the program’s internal logic.

What can attackers do with a buffer overflow?

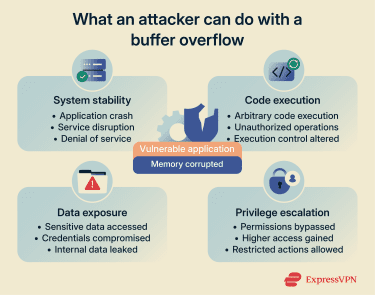

A successful buffer overflow attack gives the perpetrators some influence over how a program behaves. The level of influence hinges on where the vulnerability is and the access level of the software.

These factors can determine how much damage the attack can cause:

- The role of the vulnerable application: Exploiting a buffer overflow in a low-privilege process may limit the impact. Exploiting one in a core service, system component, or shared library can expose far more of the system.

- The level of access the application already has: Applications that manage authentication, access control, or sensitive data create more risk when their memory is compromised. Attackers can inherit the application’s permissions.

- Whether the application continues running after exploitation: Some buffer overflow attacks aim to crash a service and disrupt availability. Others rely on the application continuing to run in a corrupted state, which can allow attackers to manipulate behavior over time.

- The presence of security protections: Modern operating systems and runtimes include defenses that can limit exploitation. These protections may reduce impact, but they can’t fully prevent damage once memory boundaries are violated.

Overwriting memory boundaries

A buffer overflow attack can intentionally overwrite memory beyond a buffer’s boundaries. Those overwritten areas may include executable instructions or internal references that the program relies on to function correctly. Once altered, the application can begin following execution paths it was never designed to take.

Internal references that point the program to particular memory locations might be altered by overwritten memory. Corrupted references can shift control over program parts, leading to unintended operations.

Executing malicious code

A buffer overflow attack can also lead to malicious code being executed within a vulnerable application. Instead of following its original instructions, the program may be redirected to run code it was never meant to execute.

This happens when overwritten memory alters how the application determines what to run next. Execution flow changes, and the program may begin carrying out operations supplied by the attacker rather than its intended logic.

When this occurs, the attacker’s code runs with the same privileges as the affected application. That can allow unauthorized actions to take place, ranging from system changes to access to sensitive resources.

System crashes and denial of service (DoS)

One of the most immediate effects of a buffer overflow is instability. When overwritten memory contains data that the program needs to run, the application may crash or stop responding altogether.

In applications deployed in real-world environments, attackers can exploit this behavior repeatedly to disrupt availability. Triggering crashes at scale can turn a single vulnerability into a DoS condition, even when no sensitive data is accessed.

In these cases, the impact comes from loss of reliability rather than direct control. Services that depend on continuous uptime are especially vulnerable to this type of exploitation.

Privilege escalation and data access

Attackers can deliberately use buffer overflow vulnerabilities to gain higher levels of access within a system. By exploiting memory corruption, they interfere with how an application enforces permissions and access controls.

As mentioned above, when attackers trigger a buffer overflow in a privileged application or service, the resulting memory corruption can allow their code or commands to run with the same permissions as that application. This can effectively elevate their access beyond what they were originally granted.

Once privileges are elevated, attackers may be able to access sensitive data, perform restricted actions, or move deeper into the system. At this stage, the impact extends beyond service disruption and into broader system compromise.

Which programming languages are most vulnerable?

Some programming languages are far more prone to buffer overflow vulnerabilities than others. In practice, buffer overflows are most commonly associated with low-level languages such as C and C++.

These languages give developers direct control over memory, which is essential for system-level and performance-critical software. However, that same control also means that the language doesn't automatically stop data from going over the memory limits that have been set. When those limits aren’t enforced correctly, buffer overflows can occur.

In contrast, languages such as Java, Python, C#, and Rust reduce this risk by managing memory automatically and enforcing safety checks at runtime. In these environments, application code typically can’t write directly to arbitrary memory locations or exceed allocated storage without triggering an error. When an operation attempts to go out of bounds, the program raises an exception or stops execution rather than silently corrupting memory.

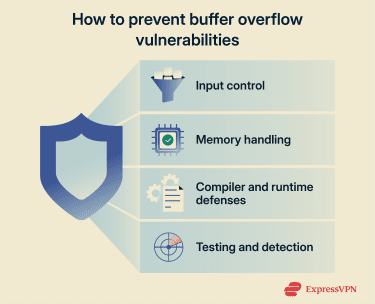

How to prevent buffer overflow vulnerabilities

No single safeguard eliminates buffer overflows entirely. Effective prevention combines safer coding practices, built-in protections provided by operating systems and compilers (tools that translate source code into executable programs and can add safety checks), and ongoing security testing throughout the development lifecycle.

Input validation and bounds checking

Many buffer overflows occur when applications accept input without verifying its size or structure. If a program assumes incoming data will always fit, memory boundaries become fragile.

Input validation and bounds checking help enforce limits before data is written to memory. Instead of trusting external input, the application confirms that data stays within expected size ranges and formats. When these checks are enforced consistently, buffers stop accepting more data than they can safely store.

Secure memory management practices

Secure memory management focuses on how applications allocate, use, and release memory. Clear ownership of memory, careful handling of buffers, and avoiding unsafe assumptions all reduce the risk of overwriting adjacent memory.

When applications manage memory predictably, failures are more likely to surface as controlled errors rather than silent corruption. This means it’s more likely that vulnerabilities will be detected and fixed during development, rather than appearing later in production.

Compiler protections and runtime defenses

Modern compilers and operating systems include defensive features designed to limit the impact of buffer overflow vulnerabilities. These protections don’t fix unsafe code, but they can make memory corruption harder to exploit and easier to detect.

Common defenses include stack canaries, which help detect when stack memory has been overwritten, and address space layout randomization (ASLR), which makes memory locations less predictable at runtime. Some platforms also use fortified standard libraries that add additional checks around memory operations.

During development and testing, runtime analysis tools and sanitizers can surface memory errors early by detecting out-of-bounds writes and invalid memory access before software is deployed.

These measures significantly reduce risk, but they don’t eliminate it. Buffer overflows often stem from logic errors or incorrect assumptions about input size, and no compiler or runtime defense can fully compensate for unsafe memory handling in application code.

Security testing and vulnerability scanning

Buffer overflows often hide in code paths that aren’t exercised during normal use. Security testing helps expose these flaws before attackers do.

Techniques such as code review, automated analysis, and dynamic testing can identify unsafe memory handling and boundary violations early in development. One widely used approach is fuzzing, which automatically feeds unexpected inputs into programs to uncover crashes and memory errors; AFL++ is an example of a tool that implements this method.

Testing doesn’t replace secure coding, but it reinforces it by catching mistakes that might otherwise go unnoticed. Regular testing is especially important for software that relies on low-level code, third-party libraries, or long-running services.

FAQ: Common questions about buffer overflow

Is buffer overflow still a serious security issue today?

Buffer overflows remain relevant because many systems still rely on low-level code and complex libraries where memory handling mistakes can occur. While modern defenses reduce risk, they don’t eliminate it.

Is buffer overflow the same as a DDoS attack?

A buffer overflow is a software vulnerability, while a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack is a traffic-based disruption. Buffer overflows involve memory corruption inside an application. DDoS attacks overwhelm systems with excessive requests from outside. Although both can cause crashes or service outages, they rely on very different mechanisms.

What is the root cause of buffer overflow vulnerabilities?

The root cause is improper memory handling. This includes failing to check input size, not enforcing boundaries, or making unsafe assumptions about how data will be used.

How do buffer overflows affect application performance?

At a minimum, buffer overflow attacks can cause crashes, freezes, or unpredictable behavior. Even when an application doesn’t fail immediately, corrupted memory can degrade performance over time. In long-running services, these issues may appear as instability, increased error rates, or gradual resource exhaustion rather than a single visible failure.

Are there tools that detect buffer overflow vulnerabilities?

Security teams use static analysis tools to scan code for unsafe memory handling, dynamic analysis tools to detect memory errors during runtime, and fuzzing tools to expose crashes by feeding applications unexpected input. Used together, these tools help identify buffer overflow risks before attackers do.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN