Nation-state cyber actors: Who they are and why they matter

Reporting on state-linked cyber operations is frequent and often high-stakes, yet the terminology, attribution, and strategic context can be difficult to interpret consistently.

This article examines why nation-state activity is treated as a distinct class of cyber risk and what it implies. We'll review common labels and groupings, operational goals, typical objectives and targets, recurring tactics, and the factors that shape impact and response.

What are nation-state actors in cybersecurity?

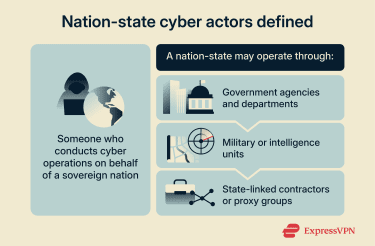

Nation-state actors are state-sponsored or state-linked individuals or groups who conduct cyber operations in support of a government's objectives. These activities are often discussed as nation-state threats: cyber campaigns assessed as connected to a particular country and intended to further national interests. Such campaigns can include espionage and intelligence collection, theft of sensitive information and intellectual property, and destructive activity.

These actors may operate within intelligence agencies, security services, ministries, or military units and may also act through contractors or other intermediaries.

Because governments may operate through private entities and proxies, and because operators can hide or blend their infrastructure and tactics, public attribution is often an educated assessment, reported with a confidence rating, rather than a definite fact.

Government-backed hackers

Government-linked hacking groups are individuals or teams assessed to operate for, or with the support of, a government, often associated with intelligence, military, or security-related agencies. Their activities are typically tied to state objectives, such as intelligence collection, surveillance of foreign targets, or broader national security goals.

Because they operate within government structures, they may have formal tasking, dedicated resources, and legal authorities or protections under their own country’s laws (though this doesn’t mean their operations are lawful in other jurisdictions or publicly acknowledged).

By contrast, cybercriminal activity is usually driven by financial gain, although in practice, the boundary can blur when states enable, tolerate, or leverage non-state groups.

State-sponsored organizations

State-sponsored organizations are non-governmental groups that conduct hacking activities in support of a government’s interests. Instead of being direct government employees, these actors can be contractors, private firms, or intermediaries that receive direction, funding, or technical support from government entities.

Governments might use these arrangements for a few practical reasons: they can scale operations quickly, draw on specialized skills, and create distance between the government and the operation, which can make it harder to prove public responsibility.

In practice, these groups may target sensitive government data, dissidents, journalists, or private-sector intellectual property, depending on state priorities.

Military cyber units

Military cyber units are cyber forces embedded within a country’s armed forces. Their purpose is to support military and national objectives, including defending military networks and conducting cyber operations as part of broader national defense plans.

These units are typically organized with clear chains of command and defined missions, similar to other military branches. For example, U.S. Cyber Command describes its mission as unifying and directing cyberspace operations, improving the Department of Defense’s ability to counter threats, and assuring access to cyberspace.

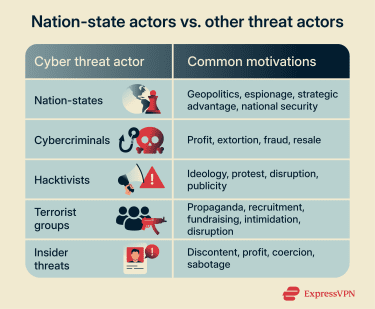

How nation-state actors differ from other threat actors

Nation-state actors are often distinguished by state-aligned objectives, access to significant resources, and the ability to sustain operations over long periods of time. Their campaigns are frequently targeted and mission-driven, especially when focused on espionage, prioritizing strategic outcomes over rapid, repeatable monetization.

Learn more: Read our explainer about hacktivism.

Historical context and origins

Public discussion of state-linked cyber operations accelerated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as investigations and incidents highlighted sustained, targeted intrusion activity.

- Late 1990s: Sustained cyber-espionage becomes visible in public reporting and government documentation. The “Moonlight Maze“ investigation examined a long-running series of intrusions into U.S. government and related networks, widely cited as an early, large-scale cyber-espionage case.

- 2007: Politically contextualized disruption becomes widely cited. The Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence analysis of the 2007 cyberattacks against Estonia describes a coordinated campaign lasting weeks and situated within a broader political conflict, helping shape how policymakers and practitioners discussed disruptive state-linked activity.

- 2010: Focus expands to industrial and critical systems. Technical analysis of Stuxnet (a computer worm discussed below) and subsequent government guidance reinforced that highly resourced operations could target industrial control environments, not only traditional IT systems.

Threat evolution over time

Nation-state tradecraft has evolved alongside the broader threat landscape. Notable shifts are in how access is gained, how dependencies are targeted, and the scale of impact when operations succeed.

- More reliance on third parties and dependencies: Attackers increasingly use suppliers, service providers, and other third parties as indirect routes into target environments. This expands the attack surface beyond the immediate organization. Verizon’s 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) executive summary reports that third-party involvement in breaches rose from 15% to 30%. The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA)’s 2025 Threat Landscape also highlights supply chain risk and indirect access through third-party providers and dependencies.

- Persistence remains a defining pattern for state-aligned activity: State-aligned intrusion sets often aim to maintain access over time, rather than carry out short, one-off operations. ENISA’s 2025 Threat Landscape report notes that while cybercriminal activity dominates overall intrusion, state-aligned intrusion sets follow and typically pursue persistence.

- Destructive operations continue to appear in some state-linked campaigns: While many operations focus on access and intelligence collection, some state-linked incidents have involved high-impact destructive malware. For example, the White House described NotPetya as a destructive and costly cyberattack that spread globally, and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) charged Russian General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) officers in connection with destructive malware campaigns that included NotPetya.

- Emerging technologies are increasing speed and scale: Microsoft’s 2025 Digital Defense Report describes AI as a factor that can accelerate and expand the scale of cyber threats, enabling adversaries (including nation-states) to operate with greater volume and precision.

Motivation and scale compared to criminal groups

Unlike primarily financially motivated cybercriminals, nation-state activity is typically shaped by strategic objectives (political, economic, military, or security-related) and may be supported by greater resources and long-term operational planning.

This difference in intent affects how operations are selected and sustained. Criminal groups tend to prioritize activities that can be repeated at scale and quickly converted into revenue, so targeting is frequently broad and opportunistic, though some can be highly targeted.

Nation-state actors are more likely to prioritize outcomes that advance national interests, even when the return is indirect or long-term. That can include building insight into an adversary’s plans, positioning for leverage during a geopolitical event, or gaining an advantage in strategic industries.

Scale also has different operational meanings. Cybercrime often scales through volume: many targets, standardized methods, and faster turnover. Nation-state activity can scale through capacity: dedicated teams, specialist skills, and sustained campaigns that can be coordinated across time, regions, and targets.

The result is often fewer targets than mass cybercrime, but a higher level of focus on achieving a defined objective, with the time and resources to continue as long as it remains valuable and feasible.

Learn more: Check out the cybersecurity spending report to see how much countries invest in their digital defenses.

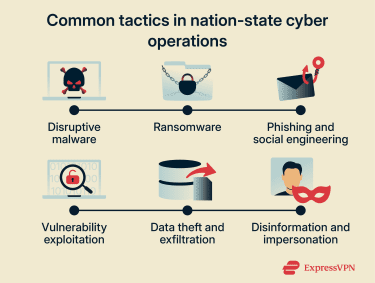

Objectives and tactics of nation-state cyber actors

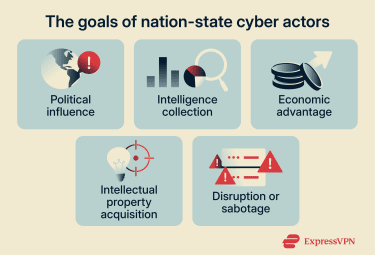

Nation‑state cyber campaigns aren’t working at random; they’re guided by strategic objectives.

According to Microsoft’s Digital Defense Report 2025, nation-state cyber activity during the reporting period prioritized espionage against traditional intelligence targets, including IT, research and academia, government, and think tanks/NGOs.

Political disruption and national interests

Some operations are designed to advance national interests by influencing political environments, shaping public perception, or undermining trust in institutions. Tactics can include information operations, targeted intrusion to obtain sensitive communications, and strategic leaks or amplification intended to create uncertainty, division, or diplomatic leverage.

Nation-states may also use cyber activity to support domestic control and external power projection, including monitoring or intimidating groups viewed as politically sensitive. These operations often prioritize strategic outcomes over immediate financial return.

Economic espionage and intellectual property theft

Economic espionage focuses on acquiring proprietary technology, research, negotiating positions, or internal strategy to support state priorities and strengthen domestic industries. Targets often include sectors tied to national competitiveness, such as advanced manufacturing, energy, telecommunications, biotechnology, and defense-adjacent supply chains.

Tactics typically emphasize covert access and sustained collection, including credential theft, exploitation of externally exposed systems, and long-term persistence to monitor communications and extract high-value data.

Infrastructure sabotage and critical disruption

Some campaigns aim to disrupt services, degrade capabilities, or hold critical functions at risk rather than collect information. These operations may target critical infrastructure operators, essential service providers, or the technology that enables physical processes.

One observed approach is to establish access to business systems first, then move to more sensitive environments that can affect operations. Where safety and reliability are involved, even limited interference can create disproportionate risk, especially if monitoring, shutdown controls, or recovery processes are impaired.

Major nation-state cyberattacks

Nation-state-linked operations have been associated with some of the most destructive cyber incidents ever recorded. Below are several examples.

Stuxnet worm: A cyberweapon milestone

The Stuxnet worm, publicly revealed in 2010, is widely cited as a turning point because it was designed to interfere with industrial control systems (ICS): the hardware and software used to monitor and control physical processes.

Stuxnet spread through multiple mechanisms, including portable media such as USB drives. It was built to reach industrial environments that used Siemens engineering tools. In particular, it targeted Siemens SIMATIC Step7, the company's software used by engineers to configure and manage industrial control devices.

Those devices include programmable logic controllers (PLCs), rugged industrial computers that control machinery by executing automated instructions (for example, starting and stopping motors, opening valves, or regulating equipment speed). Once Stuxnet reached a compatible environment, it could alter how the PLCs controlled equipment while also attempting to hide those changes from monitoring and management systems.

Stuxnet is widely cited as having targeted Iran’s uranium enrichment program, specifically centrifuges used in nuclear facilities. The malware is commonly described as manipulating centrifuge operations while displaying normal-looking readings to operators, allowing physical damage to accumulate without immediate, obvious warnings.

Public reporting (like The Washington Post) has attributed the operation to the U.S. and Israel, making Stuxnet the first publicly known example of an alleged state-developed cyber operation associated with physical damage. Its technical sophistication and deep knowledge of industrial environments set a precedent for the use of cyber capabilities as instruments of state power.

SolarWinds breach: Supply chain compromised

In 2020, the SolarWinds Orion incident became a widely cited example of a software supply-chain attack: an attack in which a trusted vendor’s software update process is compromised, leading customers to unknowingly install malicious code.

Attackers inserted malicious code into updates for SolarWinds Orion, a network management product used by many organizations, including government agencies and large enterprises. When compromised updates were distributed and installed, the attackers gained a foothold inside a wide range of networks.

A U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report described the SolarWinds incident as “one of the most widespread and sophisticated hacking campaigns ever conducted against the federal government and private sector.” The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) notes that the U.S. government attributed the activity to the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).

Ransomware as a nation-state tool

Nation-state actors have used ransomware in some cases to generate revenue that supports broader state objectives. A July 2024 joint Cybersecurity Advisory led by the FBI, with the National Security Agency (NSA) and other partners, reported that North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB) 3rd Bureau funds its espionage activity through ransomware operations targeting U.S. healthcare entities.

These actors exploit web‑server vulnerabilities, deploy malware and remote-access tooling, and conduct phishing campaigns to establish access persistence. The advisory notes that these footholds are used for system discovery, privilege escalation, and data exfiltration, and that ransomware operations can occur alongside espionage activity.

Election interference and disinformation campaigns

Beyond espionage and sabotage, nation-states also conduct influence operations intended to shape public perception and political outcomes. In 2024, the U.S. DOJ announced actions to disrupt a covert, Russian government-directed foreign malign influence campaign colloquially referred to as “Doppelganger,” including the seizure of 32 domains used to spread malign influence.

DOJ described the operation as using techniques such as cybersquatting (registering look-alike domains that mimic real sites or brands to mislead users), fabricated personas and fake profiles, paid advertising, and AI-generated content to promote false narratives online.

How to defend against nation-state cyber threats

Nation-state threats often play out at the organizational level because the highest-value targets (sensitive data, critical services, research environments, and supply chains) are owned and operated by public-sector agencies, private companies, and NGOs.

Individual users still matter, but risk reduction largely depends on how well organizations design, run, and continuously improve their security and resilience programs, including coordination with government partners where appropriate.

John Lambert, Corporate vice president and distinguished engineer at the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center, warns that “the sophistication and agility of attacks by nation-state actors will continue to evolve. Organizations must stay informed of these actor changes and evolve their defenses in parallel."

Strengthening cyber hygiene and basic defenses

Foundational security controls reduce common entry paths (like credential theft, unpatched vulnerabilities, and exposed remote access) and make follow-on movement harder. A practical baseline typically includes:

- Strong identity controls: Multi-factor authentication (MFA) at a minimum for administrative and other high-value accounts, reduced standing privileges, and tighter controls for administrator and service accounts.

- Patch and configuration discipline: Regular updates for operating systems, applications, and internet-facing services; secure configuration baselines for endpoints and servers.

- Backups and recovery readiness: Offline or otherwise protected backups, plus periodic testing of restore procedures to support recovery when disruption occurs.

- Remote access hardening: Restricted administrative access paths, monitored remote access, and strong authentication for remote management interfaces.

- Network and service exposure management: Reduce the attack surface (close unnecessary ports/services), segment critical systems, and prioritize high-risk externally exposed systems.

- Core visibility: Centralized logging for identity, endpoint, and key infrastructure events to support detection and investigation.

Learn more: Read our detailed guide on zero-trust architecture.

Employee training and threat awareness

Training is most useful when it targets the specific techniques most likely to be used against the environment (for example, spear phishing for credential theft, social engineering that targets support and recovery workflows (like password resets or MFA changes), and abuse of legitimate remote tooling once access is obtained. Program design typically focuses on:

- Role-relevant training: Additional depth for privileged users, finance, HR, executives, and help desks (common social-engineering targets).

- Exercises that match attacker behavior: Phishing simulations and reporting drills that emphasize speed, escalation paths, and “stop-and-check” decision points.

- Clear reporting expectations: Simple internal reporting channels and guidance on what to report, such as suspicious links, unexpected MFA prompts, and anomalous account behavior.

Deploying advanced threat detection and intelligence

Because many nation-state operations aim for stealth and persistence, detection and investigation capability often matter as much as prevention.

- Identity and directory monitoring: Intrusions often seek privileged access through identity systems. Joint guidance involving the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) notes that malicious actors routinely target Active Directory (AD) (Microsoft’s widely used service for managing users) and highlights how permissive default settings and complex relationships can be exploited to enable privileged access and persistence.

- Telemetry across endpoint, identity, and network: Continuous monitoring for anomalous admin activity, lateral movement patterns, credential dumping indicators, and unusual authentication flows.

- Threat intelligence integration: Use of sector and government reporting to tune detections toward current techniques and infrastructure, including third-party and supply chain exposure monitoring.

Incident response planning for high-level threats

Nation-state incidents can be prolonged and operationally disruptive, or quietly persistent. Response planning is usually treated as both a management function (governance, communications, legal/regulatory obligations) and a technical one (containment, eradication, recovery). Common focus areas include:

- Defined decision rights and escalation paths: Clear authority for containment actions, for example, isolating systems, disabling accounts, and suspending integrations.

- Evidence preservation and coordination: Processes for collecting artifacts, retaining logs, and coordinating with external partners where needed.

- Operational continuity during remediation: Plans for running critical processes while investigations and rebuilds occur.

- Exercises and validation: Regular tabletop exercises for executive leadership and technical teams to validate assumptions and reduce decision latency.

The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)’s incident response guidance emphasizes incorporating incident response into broader risk management and using a common structure and language for communicating plans and activities internally and externally.

Government policy, public-private coordination, and cyber diplomacy

Defense against nation-state operations also depends on what states do collectively and domestically, especially for critical infrastructure and cross-border incidents.

- Resilience as a policy objective: Microsoft’s Digital Defense Report 2025 frames resilience as a shared responsibility and calls out actions such as public-private collaboration, standards-setting, workforce development, and incentives through policy and regulation.

- National coordination and capacity-building: National Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs), joint advisories, information sharing, and coordinated response mechanisms can raise baseline readiness across sectors and speed collective response.

- Cyber diplomacy tools: The EU's Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox includes diplomatic measures and restrictive measures (sanctions), reflecting how states use diplomacy and statecraft to deter, respond to, or impose costs for malicious cyber activity.

FAQ: Common questions about nation-state cyber actors

What goals do nation-state actors pursue?

Nation-state actors seek a range of goals, including political influence, intelligence collection, and economic gain. Some groups work to disrupt adversaries, while others focus primarily on espionage. Motives can also overlap or shift over time, and any individual group can have its own priorities.

Why are nation-state cyber actors called “threat actors"?

In cybersecurity, the term “threat actor” refers to an individual, group, or organization that carries out, or is believed to be preparing, malicious cyber activity. Nation‑state actors can be labeled as threat actors because they can conduct operations such as espionage, disruption, or sabotage that threaten or harm other governments, organizations, and individuals.

How do nation-state attacks affect global policy?

Significant nation‑state attacks can trigger diplomatic disputes, sanctions, indictments, and international cooperation aimed at deterring or imposing costs on the responsible actors. For example, incidents involving foreign cyber interference in elections have prompted calls for updated policies and laws to strengthen election security, protect election-related systems and data, and address information operations and disinformation.

What can individuals and small businesses do to protect themselves against nation-state attacks?

Individuals and small businesses should implement basic security measures, including using least-privilege principles, patching vulnerabilities, keeping detailed logs, and monitoring risky ports. Organizations should invest in cybersecurity awareness training for their employees to help them recognize phishing scams and other prevalent attack vectors.

What are the most recent examples of nation-state cyber operations?

Recent publicly reported activity includes espionage campaigns (described by U.S. investigators as People's Republic of China (PRC)-affiliated) targeting telecommunications networks and high-value victims (such as Salt Typhoon, which the FBI said was publicly disclosed in October and November 2024 and updated in April 2025).

Operations attributed by U.S. and partner agencies to Russian state-sponsored cyber actors focused on espionage (including campaigns targeting Western logistics and technology companies) and ransomware activity attributed by U.S. authorities to North Korean state-sponsored actors, whose proceeds were allegedly laundered and used to fund further intrusions and North Korea’s illicit activities.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN