What is bluebugging, and how does it work?

Bluetooth uses pairing and device permissions to control access. When those controls are weak, misconfigured, or bypassed, a nearby attacker may access functions beyond what Bluetooth should permit.

This guide explains bluebugging as a historically important Bluetooth exploit pattern and uses it to introduce modern Bluetooth vulnerabilities and practical Bluetooth hygiene.

What is bluebugging

Bluebugging refers to early Bluetooth attacks (most notably against some 2000s-era phones), in which weak trust models and exposed Bluetooth services enabled an attacker to gain unauthorized access and trigger device actions without the owner’s awareness.

In classic cases, vulnerable devices could be manipulated to perform actions such as placing calls or interacting with messages and contacts. What made bluebugging stand out was not just data exposure, but the ability to drive device functions as if the owner had initiated them.

Understanding Bluetooth technology

Bluetooth is a short-range wireless standard that lets devices communicate without cables. It’s designed for short-range connections, typically around 30 feet (about 10–15 meters) in typical consumer use, though real-world range varies widely by device class, environment, and implementation. Phones, laptops, headphones, car infotainment systems, smartwatches, and many Internet of Things (IoT) devices use it to pair and exchange data quickly.

Most Bluetooth connections start with pairing. Pairing is how devices establish a trusted relationship by exchanging keys and agreeing on security settings, which can enable authentication and encryption when supported and configured securely. Used correctly, these protections help reduce the risk of eavesdropping and unsolicited connections.

The catch is that security depends on how the device and its software implement Bluetooth and which security options are enabled. Some devices rely on short PINs or weaker default settings, and some setups remain visible longer than necessary, especially during pairing or when discoverability settings are left open. That visibility makes it easier for an attacker nearby to spot a target and attempt a pairing-based attack.

Bluetooth has improved over time, with newer versions offering more secure pairing methods. Even so, vulnerabilities still show up in operating systems, drivers, and device firmware.

How attackers gained control in classic bluebugging

Classic bluebugging often depended on Bluetooth services that exposed sensitive functionality with weak controls. A key enabler in that era was Radio Frequency Communication (RFCOMM), a Bluetooth protocol commonly used to emulate a serial/terminal-style connection over Bluetooth.

In practice, some devices exposed powerful control interfaces behind RFCOMM-based services, which made it possible to send commands that triggered device actions.

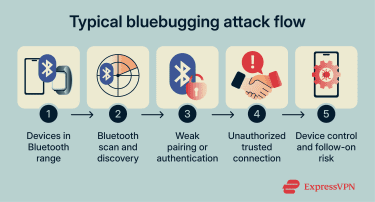

Early bluebugging attacks typically followed a predictable pattern:

- A nearby attacker scanned for Bluetooth devices within range.

- If the target device exposed a vulnerable service or had weak pairing/authentication, the attacker connected in a way the device treated as trusted.

- The attacker then misused Bluetooth profiles and services intended for legitimate accessories and control features, issuing commands that the device accepted as normal behavior.

Modern Bluetooth issues don’t usually look like the classic “phone accepts remote commands” model, but the underlying lesson still holds: when trust, authentication, or device implementation is flawed, Bluetooth can become an entry point.

Modern Bluetooth issues don’t usually look like the classic “phone accepts remote commands” model, but the underlying lesson still holds: when trust, authentication, or device implementation is flawed, Bluetooth can become an entry point.

What makes devices vulnerable to Bluetooth attacks?

Even though many Bluetooth attacks rely on technical flaws, successful compromises often come down to a few predictable weak spots:

- Overly open Bluetooth visibility: Devices are easier to target when they stay discoverable longer than necessary, especially in public places.

- Outdated software, firmware, or drivers: Vulnerabilities in Bluetooth stacks and firmware continue to pose a recurring risk. When patches lag, known issues remain exploitable.

- Weak pairing security: Simple or default pairing codes, or devices that don’t enforce strong authentication, can increase the likelihood of unauthorized connections.

- Easy-to-miss permission moments: If a pairing request is approved too quickly, or old trusted devices are never removed, it becomes easier for the wrong device to stay trusted. Over time, that can increase the risk of unwanted reconnections or access to Bluetooth services.

Newer Bluetooth standards reduce risk, but they don’t remove it. Misconfigurations and fresh Bluetooth vulnerabilities can still expose phones, laptops, wearables, and other connected devices.

Devices most exposed to Bluetooth threats

In theory, any Bluetooth-enabled device can be targeted if a Bluetooth vulnerability is present and the device is within radio range. In practice, the most attractive targets are devices that stay connected frequently, pair with many accessories, or store higher-value data.

Smartphones

Smartphones are high-value targets because they travel everywhere, typically hold sensitive personal and account data, and often keep Bluetooth enabled for earbuds, cars, watches, and trackers. That frequent, always-on use increases exposure, especially in public settings or during pairing.

On modern phones, risk often comes from newly discovered stack and protocol weaknesses or vulnerable peripherals rather than the original bluebugging mechanics.

Laptops and desktops

Computers commonly rely on Bluetooth for keyboards, mice, headsets, and conferencing gear, so Bluetooth may remain enabled for extended periods. That creates opportunities for nearby attackers when the Bluetooth stack has a weakness.

A concrete modern example is CVE-2023-45866 in BlueZ (Linux), where a nearby attacker-controlled device can inject keyboard-style input under certain conditions. This is not classic bluebugging, but it shows how Bluetooth trust assumptions can still translate into real impact.

Smartwatches and fitness trackers

Wearables are always nearby and often sync frequently over Bluetooth, which means the Bluetooth channel may stay active for long stretches. Wearables also tend to be tightly linked to a phone or other primary device. Some Bluetooth attack vectors can enable lateral spread to adjacent devices, which is one reason wearables can be relevant even when they hold less data than a phone or laptop.

IoT devices and connected cars

Bluetooth is built into many IoT and embedded devices, including smart home products, trackers, and car hands-free systems. These devices can be harder to secure because they often ship with convenience-first defaults, have limited interfaces for reviewing settings, and may receive updates less consistently than phones or computers.

Connected cars are a clear example. Hands-free systems are designed to pair quickly and stay trusted once connected, and older kits can remain in use for years. CarWhisperer (a proof-of-concept tool) was built to demonstrate an issue seen in some older car hands-free kits that used widely known default pairing codes (often “0000” or “1234”).

If the code was accepted, an attacker nearby could pair as a legitimate headset and then use the hands-free audio channel to inject audio (play sound through the system) or capture audio (record what the system sends over that connection).

History and evolution of Bluetooth threats

Bluebugging grew out of early Bluetooth security gaps, when convenience often outweighed strong authentication. Over time, Bluetooth standards improved, but Bluetooth hacking continued to evolve as new devices, chipsets, and implementations expanded the attack surface.

This timeline highlights milestones that shaped how Bluetooth risk evolved:

- Bluebugging (2004): Security researcher Martin Herfurt popularized the bluebug concept in the early Bluetooth era, showing that some vulnerable phones could be manipulated over Bluetooth to trigger device actions such as placing calls and interacting with phone functions via exposed control interfaces.

- Wearables become a target (2015): Security researcher Axelle Apvrille presented work at Hack.lu (an annual computer security conference) showing that a Bluetooth-connected fitness tracker (Fitbit Flex) could be compromised quickly within Bluetooth range, highlighting how always-on wearables expand Bluetooth exposure beyond phones and laptops.

- BlueBorne disclosure (2017): Researchers at Armis (a cybersecurity firm) disclosed BlueBorne, a set of Bluetooth vulnerabilities that, on some unpatched devices, could allow compromise without the usual pairing flow, bringing Bluetooth remote-attack risk back into the spotlight.

- BrakTooth chipset flaws (2021): Researchers disclosed BrakTooth, a set of 16 Bluetooth vulnerabilities affecting multiple chipsets across phones, laptops, and IoT devices, with the potential to cause crashes and broader impact within range.

- Fast Pair accessory risk (2026): A set of vulnerabilities tracked as CVE-2025-36911 describes a key-based pairing logic issue associated with Google device reporting. Recent coverage of WhisperPair emphasizes accessory/pairing ecosystem risks and the need for firmware updates on affected accessories.

Bluebugging vs. other Bluetooth attacks

Here is how bluebugging compares to the two other largely legacy attacks it’s most often confused with: bluesnarfing and bluejacking.

Bluebugging vs. bluesnarfing

Bluesnarfing is about data theft. An attacker connects to a Bluetooth device without permission and attempts to retrieve information such as contacts, calendar entries, text messages, or device identifiers.

Early bluesnarfing attacks exploited firmware vulnerabilities in certain phones, allowing attackers to quietly retrieve data without prompting.

Compared to bluesnarfing, bluebugging is typically seen as more intrusive because it goes beyond data copying. In practical terms, bluesnarfing is associated with information exposure, while bluebugging is associated with broader access that can enable follow-on misuse on vulnerable devices.

Both attacks exploit Bluetooth vulnerabilities, and both are more likely when Bluetooth is left on in public with overly permissive settings.

The key difference is the outcome: bluesnarfing focuses on stealing information, while bluebugging focuses on triggering device actions and control.

Bluebugging vs. bluejacking

Bluejacking is mostly a nuisance. It involves sending unsolicited messages or content to nearby Bluetooth devices, typically when a device is discoverable. There’s no real takeover here. The sender isn’t accessing the device's data or controlling it. They’re primarily pushing unsolicited content that may entice a response.

Compared to that, bluebugging is treated as a higher risk because it is not limited to message-pushing and may not be as visible in the moment.

How these attacks differ in risk and method

All three are short-range attacks and usually require Bluetooth to be enabled and the attacker to be nearby. Here’s a quick comparison:

| Bluejacking | Bluesnarfing | Bluebugging | |

| How it works | Sends unsolicited Bluetooth messages to nearby devices | Exploits a Bluetooth vulnerability to copy information from the device | Exploits exposed services or trust to trigger device actions |

| What the attacker wants | Annoy, prank, or bait a response | Steal contacts, messages, calendar entries, or identifiers | Perform actions such as calls or messages |

| Typical prerequisites | Bluetooth on, often discoverable | Bluetooth on, plus a flaw in firmware/stack | Bluetooth on plus weak pairing/authentication and exposed services |

| Level of control | None (no real access to device functions) | Limited (data access, not full command execution) | Can be high (actions performed as if by the owner) |

| Typical risk level | Low | Moderate | High |

| What you might notice | A random message, contact card, or prompt appears | Often, nothing is obvious in the moment | Often subtle, may resemble normal activity (for example, odd call or messaging behavior) |

Signs of a Bluetooth-related compromise

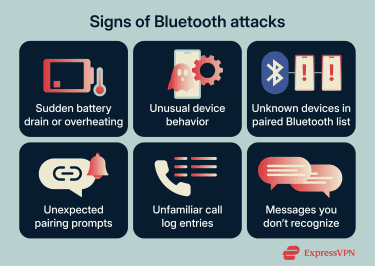

Bluetooth issues don’t always announce themselves. When something is wrong, it often shows up as small changes that feel out of place.

Unexpected battery drain or device behavior

A sudden drop in battery life is often the first thing people notice, but it's not specific to Bluetooth. Background activity from many sources can increase battery use and sometimes make a device feel warmer than expected.

You might also see odd performance issues, such as random lag, freezing, or the screen waking up when you didn't touch it. None of these confirms a Bluetooth compromise on its own, but they can be useful context when paired with other signs.

Unauthorized Bluetooth pairings

A more meaningful signal is a Bluetooth pairing you don’t recognize. Check your list of paired devices and look for names you don’t remember approving, including generic names or strings of letters and numbers. Pairings matter because they can create a trusted relationship that makes it easier for a device to interact with yours.

Also, pay attention to timing. If your phone suddenly asks to pair when you’re not actively connecting to anything, treat it as suspicious and decline it. If you find a pairing that doesn’t belong, remove it right away and keep an eye out for it returning.

A clean list of known devices is one of the simplest ways to reduce the risk of lingering unauthorized access.

Unfamiliar call or message activity

If a device shows outgoing calls or messages that weren’t initiated by you (the owner), it can indicate unauthorized use. On its own, that doesn’t prove a Bluetooth cause, but it can be relevant when paired with other signs such as unknown pairings or repeated Bluetooth prompts.

Risks and impacts of Bluetooth-related compromise

Bluetooth issues range from nuisance to high-impact, depending on the vulnerability and what the device can access.

Privacy threats

The most direct risk is loss of privacy. Depending on the weakness, an attacker may be able to access or extract sensitive information, such as contacts, messages, call history, device identifiers, or other stored data. Even when the content itself is not immediately valuable, the metadata can be used to map relationships, routines, and accounts tied to the device.

Some Bluetooth weaknesses enable more than data access. If an attacker can trigger actions that appear to originate from the device owner, such as sending messages or initiating calls, the impact shifts from exposure to impersonation. This can be used to confuse contacts, manipulate conversations, or support social engineering.

Integrity and device behavior changes

Bluetooth compromise can also affect integrity: unexpected settings changes, altered device behavior, or unwanted connections that persist because a malicious device is stored as trusted. Even without a full compromise, repeated pairing interference or connection manipulation can disrupt normal use.

Follow-on compromise and lateral movement

In modern scenarios, Bluetooth may be used as an entry point rather than the full story. If Bluetooth is used to inject input, execute commands, or exploit a stack vulnerability, it can become a stepping stone to broader compromise, such as installing malware, enabling persistence, or moving into adjacent devices that share trust relationships (for example, accessories paired to the same primary device).

Corporate espionage and data theft

When Bluetooth weaknesses affect laptops or work phones, the consequences can extend to corporate systems. Devices may store business email, internal chats, shared files, and single sign-on tokens. A compromise may translate into data loss, account takeover, or access to internal resources.

Bluetooth also appears in workplaces through keyboards, headsets, conference systems, and meeting-room equipment, which makes Bluetooth part of endpoint security hygiene.

Financial and legal implications

Direct costs can include unwanted call or messaging charges. Indirect costs can include larger account recovery abuse, fraud enabled by intercepted messages, or time spent remediating compromised accounts and devices. For organizations, response costs can include incident handling, device replacement, and investigative work to determine scope.

In many countries, unauthorized access may be treated as a cyber offense, for example, under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) in the U.S. or the Computer Misuse Act in the U.K. If the incident involved personal data, you may also have rights under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), EU data protection law.

If your number or accounts were misused, filing a report through a cybercrime portal (such as the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) or Report Fraud helps create an official record.

Learn more: Find out how to know if your phone is tapped and what to do about it.

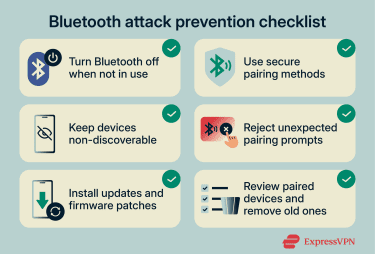

How to reduce Bluetooth risk

Reducing Bluetooth risk primarily involves limiting exposure time, tightening pairing behavior, and keeping Bluetooth components up to date. The goal is not to avoid Bluetooth entirely, but to make opportunistic attacks harder and limit the impact of newly disclosed vulnerabilities.

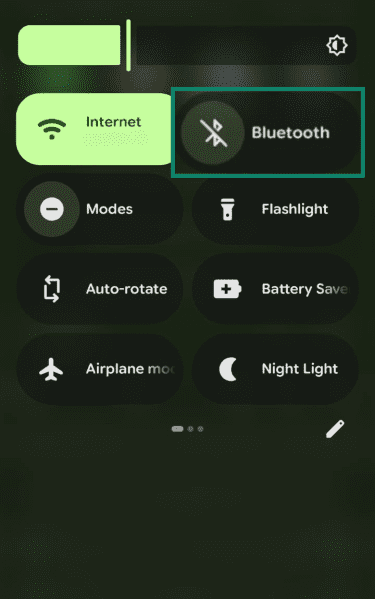

Turn off Bluetooth when not in use

The simplest and most effective step is to switch Bluetooth off when you’re not actively needing it. If Bluetooth is off, there’s no nearby radio signal for an attacker to target. This matters most in public spaces, where unknown devices are constantly within range.

Here’s how to turn off Bluetooth quickly on various platforms:

- Android: Swipe down from the top to open Quick Settings (expand if needed), then tap the Bluetooth tile to turn it off.

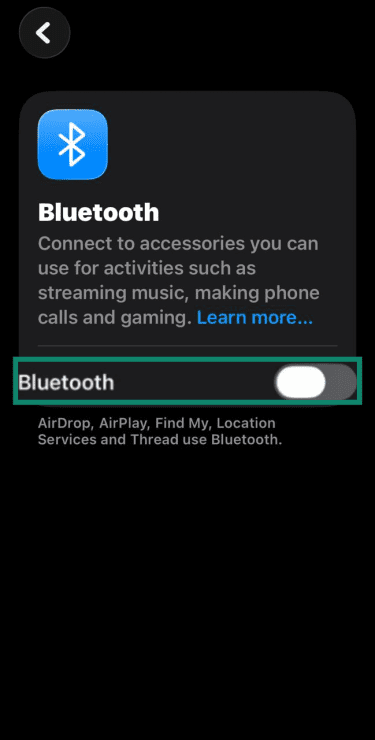

- iOS: Open Settings, select Bluetooth, and toggle it off. Turning it off through Control Center may only disconnect accessories.

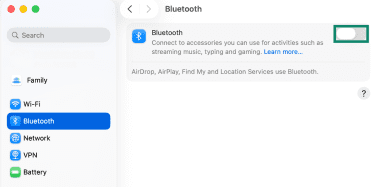

- macOS: Choose Apple menu (top-left), open System Settings, select Bluetooth, and toggle it off.

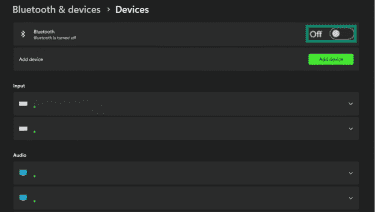

- Windows: Open Settings, select Bluetooth & devices, and toggle Bluetooth off.

Use non-discoverable behavior

Minimize time spent in pairing or discovery flows:

- Enable pairing only when actively connecting a new device, then exit the pairing screen and stop the pairing process on the accessory.

- Avoid pairing in crowded public places when possible, since nearby devices can more easily detect and target pairing activity.

- Keep the list of paired devices small and remove old pairings so fewer devices remain trusted over time.

Keep devices updated

Keep your phone and computer up to date and don’t forget the “smaller” devices that also run firmware, such as smartwatches, fitness trackers, headphones, and car infotainment systems.

When major Bluetooth flaws are disclosed, patching reduces the likelihood they will be widely exploited. If a device no longer receives updates, be more careful about using its Bluetooth in public, or consider replacing it if Bluetooth is a key feature for you.

Enable strong pairing security

Treat pairing like a security decision, not just a convenience click. When your device gives you a more secure option, choose it. Pairing methods that confirm a code or match a number add protection against certain interception and spoofing scenarios.

Also, avoid weak defaults. Some Bluetooth accessories and embedded systems still rely on simple PINs like 0000 or 1234. Where supported, change the pairing PIN or passkey. Strong pairing won’t fix every Bluetooth vulnerability, but it removes easy wins that attackers still rely on.

Monitor Bluetooth pairing requests

Some attacks start with one small mistake: approving a pairing request you didn’t initiate. If a pairing request appears out of nowhere, reject it. Pair devices only when you’re the one starting the connection.

It also helps to clean up your trusted device list. Remove old devices you no longer use so they can’t remain trusted indefinitely. A shorter, well-known list reduces the chances of something slipping in and staying there.

Use trusted security software

Using trusted security software can flag suspicious activity if a Bluetooth compromise is used as an entry point for spyware or other malware. Also, it can help highlight risky settings or missed updates that leave you more exposed.

On laptops, stick with built-in protections where possible: Windows Security (Microsoft Defender) on Windows, and XProtect and Gatekeeper on macOS. These won’t prevent Bluetooth-layer exploits, but they can help catch malicious software or follow-on activity.

On Android and iOS, official app stores and platform protections can help reduce exposure to risky apps. Also, controls like privacy indicators can help flag unexpected microphone use, and app permission settings can help review which apps have access to Bluetooth.

FAQ: Common questions about bluebugging

How does bluebugging work in real-world scenarios?

Bluebugging typically involves exploiting a vulnerability or insecure Bluetooth setup to gain unauthorized control of a device over a short range. From there, an attacker may trigger actions like calls or messages, depending on the device and the flaw. Risk generally increases with unpatched/outdated software, discoverable pairing, and weak pairing security.

Is bluebugging illegal?

In many jurisdictions, yes. Bluebugging typically involves unauthorized access to someone else’s device and data. Similar conduct is commonly covered by computer misuse/cybercrime laws, though the exact rules vary by country.

Can antivirus software detect bluebugging?

Not reliably. Bluebugging exploits weaknesses in Bluetooth implementations (such as the Bluetooth stack, profiles, or firmware), which antivirus software may not monitor directly. Antivirus tools may help if the attack results in spyware, malware, or suspicious activity on the device. However, trusted security software and enabling built-in privacy features on smartphones can reduce the chances of bluebugging.

What can businesses do to protect their assets against bluebugging?

Reduce Bluetooth exposure and enforce patching. Organizations can keep OS and Bluetooth driver updates current, disable Bluetooth by default on managed endpoints unless required, and restrict discoverability on corporate devices to better protect assets.

Policies should also define approved Bluetooth accessories, require regular reviews of paired devices, and include staff training to reject unexpected pairing prompts.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN