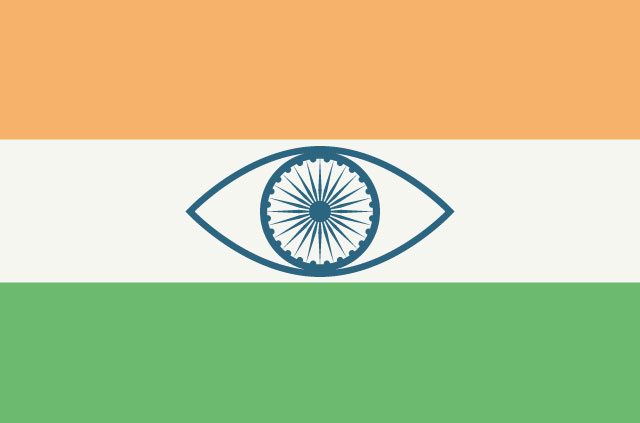

India proposes mass surveillance measures in new IT bill

Update on June 2, 2022: In light of data retention regulations, ExpressVPN no longer has physical servers in India. Find out more.

India’s government is taking drastic steps to surveil and censor content on social media platforms in an attempt to stem what they consider “unlawful information or content.”

Proposed last year and expected to take effect soon, the amendments to Section 79 of India’s IT Act, also known as the Intermediary Guidelines, require companies such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Youtube, and Netflix to identify and remove content deemed inappropriate within 72 hours and ban the user who posted the content.

The proposal also requires companies to proactively monitor what’s being posted on their platforms at all times, effectively performing mass surveillance on all their users, posts and private messages.

Why is India introducing mass surveillance measures?

Since their introduction into India, social media platforms wield substantial power over its users; WhatsApp, in particular, has a vast influence over the quarter of a billion people in India who use the messaging app regularly.

This influence has allegedly helped fan the flames of fake news and violence across India. The government is keen to surveil WhatsApp in a bid to find the source of fake news, but the platform’s break end-to-end encryption prevents this.

Facebook’s WhatsApp currently supports end-to-end encryption, meaning the company can’t see any of their users’ messages and therefore can’t turn anything over to law enforcement or governments who request them.

WhatsApp has made steps to stem the tidal wave of news spreading—there is now a limit on how many times you can forward a message.

Pointing the blame at social media companies, however, fails to address the persisting issues facing the country with increasing religious violence and the highest recorded wealth inequalities in a generation.

The timing of India’s Intermediary Guidelines is also noteworthy—with general elections happening only two months from now, it would suit the ruling Bharatiya Janata party’s interest to control the associated online discourse.

With social media playing a central role in campaigning, the rush to implement vaguely defined laws that would control the conversation (and campaign) to favor what the ruling party would consider “unlawful” is convenient.

An “authoritarian bent” in India’s laws

The new rules have many privacy advocates and critics deeply concerned for India’s continuing decline in its freedom of speech.

India is no stranger to censoring and surveilling citizens—from internet shutdowns to attempts to censor adult content, the government has taken significant steps to curb dissent and free speech for its almost half a billion internet users.

“The proposed changes have an authoritarian bent,” Apar Gupta, executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation told the New York Times. “This is very similar to what China does to its citizens, where it polices their every move and tracks their every post on social media.”

Despite pressure to pass the law, crucial details are yet to be defined, such as the form of punishment for companies failing to comply with the new rules. And with such a loose definition of what is considered “unlawful,” there is also plenty of room for abuse by the ruling BJP party, from blocking WhatsApp campaigns to taking down opposing party posts on Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, and TikTok.

Setting a precedent for other countries

If Section 79 of India’s IT Act passes, it is up to companies to decide whether they want to comply or face the unknown consequences.

If online companies were to comply, like Netflix almost did, it would set a precedent for other countries to demand companies limit content. And once the surveillance technology is developed and implemented by India, the tech will be much easier for other countries to use.

Europe is currently trying to pass its own mass surveillance measures under the guise of “Terrorist Content Regulation,” which would also turn social media platforms into sensors and monitors the EU says it will use to identify and remove content relating to terrorism. Once the measures are in place, though, governments could expand surveillance to harvest almost limitless pools of user data.

Possibility of overturning new measures

Although these Intermediary Guidelines have been passed and waiting to be implemented in India, there is hope that the High Court will overturn it—as it has in the past.

Passing these regulations is one thing, but enforcing them is another. In the likely event that companies do not comply, the lack of clearly defined punishments will make it difficult for the government to impose any fine or sanctions.

While we wait to see how this law plays out, consider whether you want to keep Facebook, WhatsApp, or other social media, and have a look at more secure messaging systems for you and your friends to use like Signal.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN