What is a cyberattack? Understanding the basics

Most cyberattacks don’t start with movie-style hacking. Instead, they begin with something simple that works at scale, like credential theft via a fake login page. Targets range from personal accounts to critical services, depending on what data, money, or access is valuable.

This guide explains what cyberattacks are, their impact, and how they're commonly detected and prevented.

What is a cyberattack?

A cyberattack is a deliberate, malicious attempt to gain unauthorized access to, or disrupt, degrade, or damage digital systems (devices, networks, or online services). Attackers may target organizations or individuals to steal information, interrupt operations, or take control of accounts and infrastructure.

Many cyberattacks can be described as a sequence of stages, though real incidents may skip steps, repeat them, or combine multiple stages at once:

- Reconnaissance: Threat actors research the target from the outside to identify weaknesses and choose the most effective attack path. They might collect details about software versions, network infrastructure, employee roles, and internet-facing services.

- Weaponization: Attackers prepare or adapt capabilities for the operation, such as phishing lures, malware, or exploit code, and may set up supporting infrastructure (e.g., domains or command servers).

- Initial compromise: Attackers gain their first foothold inside the target environment. Common methods include phishing emails with malicious attachments, exploiting vulnerabilities in public-facing services, or using stolen or weak credentials to log in directly. Malicious code then activates on the compromised system.

- Command and control: Compromised systems establish communication with the attacker's external infrastructure. This connection enables remote instructions, cross-compromised-system coordination, and data transfer.

- Internal reconnaissance: From inside the network, attackers map the environment to understand its structure. They identify what systems exist, which accounts have elevated privileges, where sensitive data is stored, and how systems connect to each other.

- Privilege escalation: Attackers seek higher permissions and broader visibility within the environment. They may exploit software vulnerabilities, steal administrative credentials, or abuse misconfigured systems to gain administrative control.

- Lateral movement: Control spreads from the initial system to additional devices and accounts. Attackers reuse credentials or use trusted connections to move through the environment, reaching sensitive systems that weren’t directly exposed.

- Impact: The attack reaches its objective once attackers gain sufficient access and control. Outcomes may include data theft, service disruptions, system manipulation, or file encryption for ransom demands.

In practice, the pace varies; some stages happen in minutes, while others unfold over days or weeks, depending on the attacker’s goal and the target environment.

Types of cyberattacks

Cyberattacks take many forms, each with a specific way of gaining access, interfering with systems, and extracting value from data, as seen in some of the biggest hacks ever. Understanding how these attacks work helps recognize their signs and prevent them.

Brute-force attacks

A brute-force attack uses a trial-and-error method to gain unauthorized access. Attackers repeatedly guess passwords or login credentials until they find a working combination.

Without proper account lockout rules or rate limits, attackers can quickly automate large numbers of login attempts. Attackers don’t always try endless combinations against one account. Variations such as password spraying use one common password across many accounts to avoid lockouts.

Weak, short, or reused passwords make brute-force attacks far more effective. Longer, unique passwords can greatly increase the work required, especially if attackers obtain password hashes and attempt offline cracking. Multi-factor authentication (MFA), especially phishing-resistant methods) Further reduces the odds of account takeover.

Malware

Malware refers to software or code intended to perform unauthorized, harmful actions on a system. It can steal sensitive information, disrupt services, or enable unauthorized access. Malware can undermine the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of data, and in some cases may give attackers remote control of affected systems.

For example, ransomware is a form of malware that encrypts files or renders systems unusable, often in combination with data theft and extortion. Drive-by downloads are a common delivery method: someone unknowingly visits a compromised website (or malicious ads/scripts), and malware may be downloaded and installed without their knowledge.

Man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks

In a MitM attack, an attacker positions themselves between two communicating parties to intercept and/or alter data in transit. This can occur on unsecured Wi-Fi networks or through compromised routers, and may be used to steal credentials, inject malicious content, or eavesdrop on conversations.

Structured Query Language (SQL) injection

SQL injection occurs when attackers exploit flaws in an application's handling of user input, allowing them to manipulate database queries and execute unauthorized commands. This can expose customer records, financial data, or credentials, and in some cases, allow data to be modified or deleted.

Social engineering

Social engineering manipulates people into taking unsafe actions, such as revealing sensitive information or clicking on malicious links.

The most common form is phishing, in which attackers impersonate trustworthy entities via email, text messages, and social media. These often contain malicious links (URL phishing) or attachments. Other forms of social engineering include:

- Pre-texting: Attackers invent a believable scenario, such as posing as IT staff or bank officials, to trick victims into revealing confidential information. This relies on building trust through a fabricated story rather than sending malicious links or files.

- Baiting: Victims are lured with something enticing, such as free software, giveaways, or infected USB drives left in public places. The goal is to trigger curiosity so that victims willingly install malware on their devices.

- Quid pro quo: Attackers offer fake services or benefits, like technical support, in exchange for login credentials or access. Victims believe they're receiving help while handing over sensitive information.

- Tailgating (piggybacking): An unauthorized person follows an authorized employee into a restricted physical area to bypass physical security controls by exploiting politeness or lack of vigilance.

- Scareware: Victims see alarming fake warnings about infections or legal trouble to pressure them into quick action. They’re tricked into installing malware or paying for fraudulent “solutions.”

Lately, attackers have also used generative AI to produce more convincing phishing content and to create voice impersonations used in vishing and related scams.

Read more: How to stay safe from AI scams.

DDoS attacks

A distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack aims to make a server, service, or network unavailable to legitimate users. Attackers generate traffic from many sources, often using a botnet, and sometimes via reflection/amplification, to flood the target with large volumes of requests or packets.

This traffic can exhaust the target's resources (bandwidth, processing power, or memory), causing services to slow down, time out, or crash entirely. The goal is typically to disrupt operations, extort payment, or serve as a distraction while other attacks occur.

Zero-day exploits

A zero-day exploit targets a previously unknown vulnerability in hardware, firmware, or software. They’re called “zero-day” because the vendor has had little to no time to develop and release a fix before exploitation begins. As a result, a patch may not exist yet, and defenders may have limited immediate options beyond mitigations and workarounds.

Impacts of cyberattacks

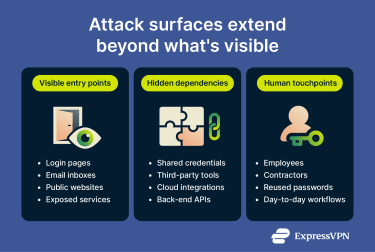

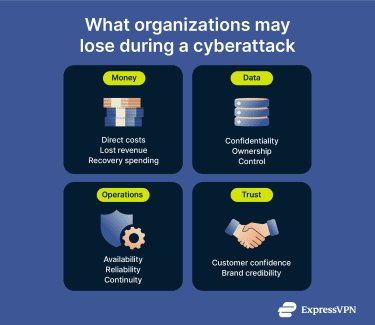

Cyberattacks rarely cause a single, isolated problem. When attackers steal data or block access to systems, victims may face financial, reputational, and operational losses.

Financial loss

For organizations, a data breach can cost millions in incident response, forensic investigation, legal support, regulatory fines, customer notification, system restoration, and business downtime.

Ransomware locks organizations out of critical systems, disrupting operations and revenue. Even without paying the ransom, recovery efforts, downtime, and third-party remediation can create substantial expenses, and many campaigns also involve data theft and extortion.

For individuals, financial loss often appears as account takeover and identity fraud. Stolen personal data can be used to make fraudulent purchases, attempt to open new credit accounts, or impersonate someone in ways that create long-term credit harm and legal complications.

Data theft

Cyberattacks frequently result in theft of confidential information. When attackers target organizations, they often steal customer records, employee data, financial information, healthcare records, and intellectual property. This can lead to legal liability, regulatory penalties, and loss of customer trust. Stolen business data can also expose trade secrets and provide access to internal systems.

When attackers target individuals, they can steal personal data such as login credentials, banking details, government ID numbers, and contact information. Criminals use this data for identity theft, account takeovers, financial fraud, or impersonation.

In either case, attackers might reuse stolen credentials to access other accounts or sell them on underground markets.

Operational disruption

Cyberattacks can disrupt daily operations by cutting off access to critical systems and data. Organizations may experience extended service outages that halt internal workflows and customer-facing services. Recovery can take days to weeks, or longer in severe cases, during which productivity remains impaired.

Reputational damage

A cyberattack can damage a company's reputation even after systems are restored. When attackers expose customer or employee data, organizations signal weak security controls and lose trust with customers, partners, and regulators.

Customers may abandon the brand, and the breach becomes associated with the company for years. This reputational harm can translate into lost revenue, often exceeding the immediate recovery expenses.

Individuals might also take a reputational hit when attackers leak personal information, leading to embarrassment, blackmail, or damaged relationships.

How cyberattacks are detected

Most attacks aren’t immediately evident. Victims and security teams usually detect them by piecing together small signs from network traffic and device behavior.

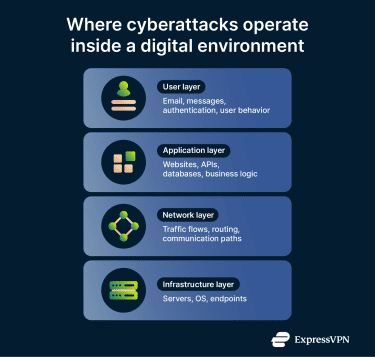

Network monitoring and anomaly detection

Network monitoring analyzes traffic moving between systems, both internally and externally. The goal is to establish a baseline for network behavior to then identify deviations that may indicate malicious activity. Network monitoring is often delivered through network detection and response (NDR) tools, which analyze traffic and metadata to detect suspicious patterns and generate alerts.

Detection commonly uses two approaches: signature-based (matching known attack patterns) and anomaly-based (flagging deviations from normal behavior). Many tools combine both to catch a wider range of threats.

Anomalies don’t necessarily indicate an attack, as legitimate activity can also deviate from normal patterns. Some intrusions can produce network signals consistent with lateral movement, command-and-control (C2) communication, or data exfiltration, though attackers may also try to mimic normal traffic to avoid detection.

Endpoint security alerts

Endpoint security focuses on individual devices, such as laptops, desktops, and servers, rather than the entire network. A common example is antivirus software on a personal computer. In many organizations, endpoint monitoring is delivered through endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools that collect device activity to detect threats and support investigation.

Some organizations use extended detection and response (XDR) to combine signals from tools like NDR, EDR, identity, and cloud telemetry, then correlate them into higher-confidence alerts and response actions.

EDR tools look for known malware and unusual behavior, such as unexpected processes, unusual file changes, or signs of credential abuse. When they detect something suspicious, they generate alerts that provide context on what was observed and may quarantine a file or isolate the device.

User behavior analytics

User and entity behavior analytics (UEBA) learns what normal behavior looks like for each user and device over time. It builds profiles based on patterns, for example, when someone logs in, which systems they access, and how much data they usually transfer.

When activity deviates significantly from these patterns, UEBA flags it as suspicious. This approach detects threats that bypass traditional security measures, such as compromised accounts or insiders abusing legitimate access.

Read more: Insider threats.

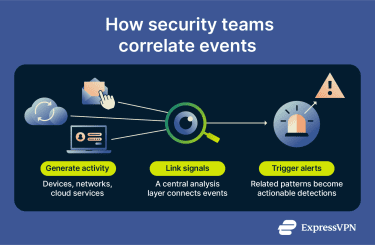

Security information and event management (SIEM) systems

SIEM systems centralize security data from servers, network devices, security tools, and cloud applications. Usually, attackers spread their actions across multiple systems, which can make individual events seem harmless in isolation.

For example, a single failed login, a new process starting on a device, and a brief outbound connection may not trigger alerts individually. When SIEM correlates them into a single timeline, it can help reveal suspicious activity. By normalizing logs, linking related events, and alerting on patterns across systems, SIEM platforms can help detect attacks that might otherwise be missed.

How to prevent cyberattacks

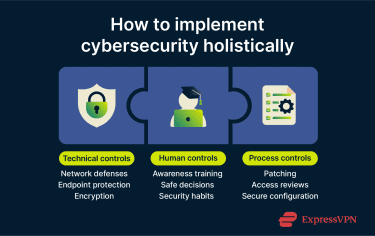

No single tool stops every threat, so individuals and organizations can reduce risk by applying multiple, complementary cybersecurity measures.

Security software and tools

Security tools are the technical foundation of cyber defense, controlling access, detecting malicious activity, and reducing exposure. These tools only remain effective when they're configured correctly, monitorred and kept up to date.

- Firewalls: Control the flow of network traffic to prevent unauthorized access. At home, built-in device and router firewalls can help. In organizations, firewall policies often follow a deny-by-default, allow-by-exception approach, with logs reviewed and rules regularly maintained.

- Antivirus software: Tools can scan for malware (and sometimes scan traffic at gateways), but their effectiveness depends on regular updates. This is often a good option for individuals seeking everyday malware protection.

- Endpoint protection: Often combines malware prevention with behavioral detection and investigation features. They’re designed to run continuously and reduce security gaps, though no endpoint control is impossible to evade.

- Intrusion prevention: Intrusion prevention systems (IPS) inspect traffic and can block suspicious activity before it reaches its targets, adding a preventive layer beyond basic traffic filtering.

Security awareness

Human behavior influences cybersecurity outcomes. Even well-secured systems remain vulnerable if common attack techniques aren’t recognized or if suspicious activity isn’t handled safely.

Security awareness helps people identify suspicious messages, unexpected requests, and abnormal system behavior before falling into common traps.

Organizations often use phishing simulations to test and improve employee responses to realistic attack scenarios. Individuals benefit from staying informed about current tactics, including AI-powered impersonation and social engineering that can make scams more convincing.

User behavior plays a critical role in preventing malware infections. Attackers may rely on tricking a person into enabling risky features (such as macros) or running unexpected files. Caution with these prompts can reduce the risk of malicious code executing.

Access control and authentication

Access controls limit how far attackers can advance after compromising credentials or systems. Restricting privileges and strengthening authentication reduces both attack success and impact.

- Least privilege principle: Users should only have the access level they actually need. At home, this means using a standard account for daily tasks instead of an administrator account. In organizations, permissions should match role requirements and may be enforced through zero-trust access controls and just-in-time (JIT) elevation, which grants admin access only when needed and for limited periods.

- Granular access: Limiting which apps, devices, and services can access accounts reduces unnecessary exposure. In organizations, detailed permissions can limit what attackers can reach after an account is compromised, reducing lateral movement opportunities

- MFA: Requires two or more authentication factors (e.g., a password plus an app code or biometric), making passwords alone less useful to attackers.

Regular updates

Unpatched software remains one of the most common paths attackers use to gain access. Regular updates reduce risk by addressing known vulnerabilities.

Timing matters. For internet-facing systems and services, applying security patches as quickly as feasible, especially when a vulnerability is known to be exploited, provides stronger protection. Automatic updates can also reduce the chance of missing important fixes.

Read more: Cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

FAQ: Common questions about cyberattacks

What happens during a cyberattack?

During a cyberattack, an attacker exploits a weakness in software, systems, or human behavior. They may use phishing, stolen credentials, malware, or unpatched flaws to compromise accounts or systems. Once a foothold is established, the attacker may steal data, spy, disrupt services, encrypt files for ransom, or create backdoors to return later.

How can individuals safeguard against cyber threats?

Individuals can reduce risk by using reliable security tools, such as antivirus software and multi-factor authentication (MFA). Phishing-resistant MFA can prevent many credential-based takeovers, even if an attacker already has a valid username and password, because the authentication is bound to the legitimate site and can’t be replayed on a fake login page.

What should you do after a cyberattack?

After a cyberattack, you need to take steps to contain the incident and reduce the chance of recurrence. Quickly isolate or segment affected systems (as appropriate) to limit spread and protect unaffected assets. Preserve logs and evidence so security teams can investigate what happened and how the attacker got in. Then contain and remove the threat, restore systems from known-good backups, and monitor closely for signs of persistence or reinfection.

How to educate employees about cybersecurity?

Organizations can educate employees about cybersecurity through ongoing awareness programs that cover common threats like phishing and unsafe browsing. Regular refreshers, short simulations, and clear reporting guidance help reinforce secure habits over time. Role-specific training keeps the content relevant and supports a stronger security culture as risks evolve.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN