What is an open port? A guide to network vulnerabilities

Your devices constantly exchange data across networks. This exchange happens through network ports, which act like numbered doorways that help direct traffic to the right app or service.

An open port isn’t inherently dangerous. In fact, you need them to access internet services like browsing, gaming, streaming, or checking your email. However, they can become security risks when they’re open unnecessarily, when the service behind them is poorly protected, or when they’re exposed to the internet unintentionally.

This guide explains what open ports are, how they work, the real risks they create, and how to check and secure them.

What is an open port?

Every device on a network has an Internet Protocol (IP) address. That address identifies the device to which data should go. Ports identify which service or app on that device should receive the data. A port is simply a numbered endpoint (from 0 to 65535) that your operating system (OS) uses to route network traffic, for example, to send web traffic to a web server, not an email app.

An open port is when a specific piece of software (like a game server or printer driver) tells the OS, “I am claiming Port X. If any data arrives with that number on it, send it to me.” The OS is then ready to forward any traffic arriving on that port to the service that claimed it.

In technical terms, we say the application is bound to the port and is in a “listening state.”

By itself, an open port is not a flaw or a vulnerability. It only becomes a risk when:

- The port is reachable by people or systems that shouldn’t have access.

- The service listening on the port is weakly secured, misconfigured, or unpatched.

In short, an open port is a doorway. The risk depends on who can reach it and what’s behind it.

Types of open ports

Not all ports are equally exposed. The most useful way to think about them is who can connect. In practice, that depends on which network interface a service is listening on (for example, loopback vs. Wi-Fi/Ethernet vs. all interfaces).

Local-only ports

Only your device can connect to them. This usually happens when a service listens only on the loopback interface. They’re often used by:

- System services

- Background processes

- Developer tools

They usually present very little risk because they’re not reachable from the network.

Local area network (LAN) open ports

Other devices on the same network can reach them when a service listens on your Wi-Fi or Ethernet interface. Examples include:

- Printers

- File-sharing services

- Smart home hubs

This risk may be acceptable on a trusted home network. On shared or untrusted Wi-Fi, however, these ports are far more exposed.

Internet-facing ports

Internet-facing ports can be reached from outside your local network. They carry the highest risk because they are visible to third parties.

Most home routers use Network Address Translation (NAT), which swaps all the private IP addresses of the devices on your home network with a single public IP address. This means an open port on your laptop is usually invisible to the internet because the router acts as a basic firewall.

A port only becomes internet-facing if you specifically tell the router to “forward” that traffic to your laptop or if a protocol like Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) does it automatically.

Port forwarding

Port forwarding is a manual rule on the router that says, “Traffic arriving on this external port should be sent to this device and service inside the network.” It generally involves directing traffic from a specific external port to a specific internal IP address and port.

Because port forwarding is deliberate and static, it’s usually easier to spot, review, and remove when no longer needed.

Universal Plug and Play (UPnP)

UPnP is the “convenience trap.” It allows apps and devices to open ports automatically without asking you. These mappings:

- Can appear and disappear without you doing anything.

- May be easy to miss unless you regularly inspect your router settings.

- Are often enabled by default on home routers.

UPnP makes it easier for you to connect to the internet, but it’s also easy for malicious actors to find these auto-opened doors.

Most serious port-related security incidents involve services that were unintentionally exposed to the internet.

Port number ranges

Ports are organized into three standard ranges:

- Lower-numbered ports (0–1023): Commonly associated with well-known services like HTTP, HTTPS, and Secure Shell (SSH). On many Unix-like systems, binding to these ports requires elevated privileges.

- Registered ports (1024–49151): Assigned to specific applications and vendors.

- Dynamic/private ports (49152–65535): Often used for temporary outbound connections.

These ranges describe how the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) manages and assigns ports. A port’s number doesn’t tell you whether it’s safe or dangerous.

How open ports work

Network connections are defined by a combination of an IP address, a port number, and a transport protocol (usually Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) for reliable connections or User Datagram Protocol (UDP) for faster traffic). That’s why they’re often called TCP/IP ports.

Internet traffic flows two ways:

- Outbound traffic: When you initiate a connection, for example, by clicking on a link, your router remembers that you asked for that data. When the website replies, the router lets that specific data in.

- Inbound traffic: You only need an open port when an external device wants to initiate a new connection with you without being invited first.

The success of an inbound connection depends on whether a service is listening, firewall rules, and router and NAT settings. If traffic reaches an open port and a service is listening, the OS hands the connection to that service. This is normal and useful when intentional. It becomes dangerous when the service was never meant to be reachable.

Common examples of open ports

Some services use well-known ports by default, while others rely on a smaller range of ports depending on how the connection is set up, which is why virtual private network (VPN) traffic is often associated with specific ports.

Here are some typical services and their related ports.

| Service | Port/Protocol | Typical use case |

| HTTP | 80/TCP | Unencrypted web traffic |

| HTTPS | 443/TCP | Secure, encrypted web traffic |

| SSH | 22/TCP | Secure, remote access to a computer or server |

| Domain Name System (DNS) | 53/UDP and 53/TCP | Translates URLs into IP addresses |

| Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) | 25/TCP | Sending emails between servers |

| Server Message Block (SMB) | 445/TCP | Windows file and printer sharing |

| Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) | 3389/TCP | Windows Remote Desktop Protocol |

| Post Office Protocol version 3 (POP3) | 110/TCP | Retrieving email from a mail server |

| Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) | 143/TCP | Accessing and syncing email across devices |

Attackers often scan these common ports first. However, they also scan higher or less common port numbers (rare ports) to find services running in unusual places.

Non-standard port usage

Services can run on any port, not just their defaults. People often use non-standard or alternative ports, like 8080 for HTTP traffic or 8443 for HTTPS traffic, to avoid conflicts or opportunistic scanning.

This is referred to as “security through obscurity,” where hiding something may reduce attention but does not, on its own, make it more secure. It also doesn’t replace strong authentication, patching, and firewall rules.

Security risks of open ports

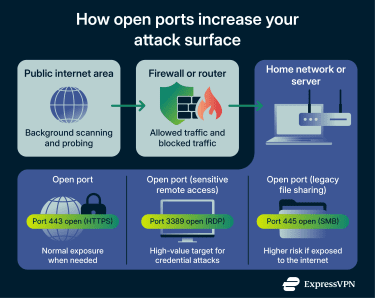

Open ports are a normal part of networking. The risk comes from exposure. If a service is reachable, it can be discovered, probed, and sometimes exploited, especially if it’s internet-facing and poorly secured.

The risk isn’t all-or-nothing. It depends on where the port is exposed and what’s behind it. The table below is a rule of thumb to help assess common scenarios.

| Scenario | Risk level | Why it matters |

| Local-only port | Low | Not reachable from the network |

| LAN, trusted home network | Low to medium | Accessible to nearby devices on the same network |

| LAN port (shared or untrusted Wi-Fi) | Medium | Reachable by nearby devices you do not control |

| Internet-facing port | High | Discoverable by global scanners |

| Port-forwarded service | High | Explicitly exposed and reachable from the internet |

| UPnP-opened port | High | Exposure may be automatic and easy to miss |

| Patched, authenticated service | Lower | Risk reduced but not eliminated |

| Unpatched or legacy service | Critical | Common exploit path |

The most common open port security risks appear when:

- A port is opened by accident.

- The service behind it isn’t properly hardened.

- An admin interface was meant to stay on the local network.

- A remote access service uses weak credentials.

- An old service hasn’t been patched.

An open port is only as secure as the service listening behind it and the access controls protecting it. That’s why security guidance so often emphasizes reducing the exposed attack surface and tightening access paths.

Common threats

An open port isn’t the attack itself. It’s the entry point. If it’s there, it attracts attention, even if no one clicks anything or installs malware. Closing unused ports breaks the attack chain early by removing the initial point of contact.

Here are some of the more common dangers associated with open ports:

- Brute-force attacks: If your RDP port is open to the internet, attackers can use automated software to try thousands of passwords per second until they get in. You’re especially vulnerable if access isn’t rate-limited or doesn’t require multi-factor authentication (MFA).

- Wormable exploits: These are vulnerabilities that let malware spread automatically from one computer to another over a network. For example, if you are running an old version of a service (like Windows File Sharing) on an open port, a hacker can send a “poisoned” packet of data, allowing them to take control of your computer without you ever clicking a link or downloading a file. This is how famous attacks like WannaCry spread.

- Misconfiguration exposure: Sometimes, the danger isn’t malware; it’s an admin page, a file-sharing service, or a remote access tool intended only for local network use but that is accidentally exposed due to permissive rules or router settings such as port forwarding.

- UPnP vulnerabilities: UPnP lets devices automatically request port mappings from a router so they can accept inbound connections. This can expose internal systems to external access without you realizing it, especially when enabled by default on home routers.

A practical tip: If a port is open for something you don’t recognize or actively use, investigate it.

Why public Wi-Fi is riskier

On public Wi-Fi, you share the network with strangers and have no control over how it’s configured. Nearby devices may be able to:

- Scan for open ports.

- Probe shared services.

- Intercept unencrypted traffic.

For example, your device might have open ports for “File Sharing” or “AirDrop.” On your home network, this is fine. In a coffee shop, however, a stranger three tables away can probe these ports and try to see your private files.

How to check which ports are open

When checking open ports, you should look for two things: what is open on your computer (local) and what is visible to the internet (external).

Checking what’s listening locally

These commands are run in your OS’s built-in command line and show which services are actively listening for connections on your device.

Windows (Command Prompt)

Open Command Prompt, then type: netstat -ab

Result entries marked as LISTENING indicate open ports. You’ll also see the local address (which includes the port number) and a Process ID (PID) you can use to identify the app or system service using that port.

Windows (PowerShell)

Open PowerShell, then type: Get-NetTCPConnection -State Listen

This shows listening TCP/IP ports in a more readable format than netstat, including the local port and connection state.

For UDP listeners, type: Get-NetUDPEndpoint

If a port is open, it will appear as a listening entry with a local port number and no established remote connection.

macOS

Open Terminal, then type: sudo lsof -nP -iTCP -sTCP:LISTEN

This lists the processes listening on TCP ports. The output lists all open ports along with the name of the process using them.

Linux

Open a terminal, then type: sudo ss -lntup (on some systems, you can use netstat -lntup instead).

This displays listening TCP and UDP sockets. Open ports appear as entries in the listening state, often with the associated process name or ID.

Important note: A port can be listening locally and still be blocked from the internet by a firewall or router.

Checking externally (what others can reach)

Your local check won’t show you what your router is blocking. To see your internet-facing profile, test your public IP from outside your network. On Windows, use PowerShell’s Test-NetConnection with your public IP and port.

On macOS or Linux, nc -zv does the same. Online port checkers can also confirm reachability.

You can also use a port scanning tool like Nmap. For a basic scan, type nmap -v <target>, which reports open ports as they are discovered instead of waiting for the scan to finish.

By default, this scans 1,000 common TCP ports and reports whether they’re open, closed, or filtered:

- Open: Reachable and listening. The world can see you.

- Closed: Reachable, but no service is listening.

- Filtered: The safest state. A firewall is completely hiding the port, so malicious actors can’t even tell if you’re online.

Nmap may report mixed states (such as when a firewall blocks probes inconsistently), which usually indicates filtering or unclear reachability rather than a service being openly accessible.

Security teams proactively scan their own systems for the same reasons attackers do: to find exposure before it’s abused and fix it.

How to secure open ports: Practical advice

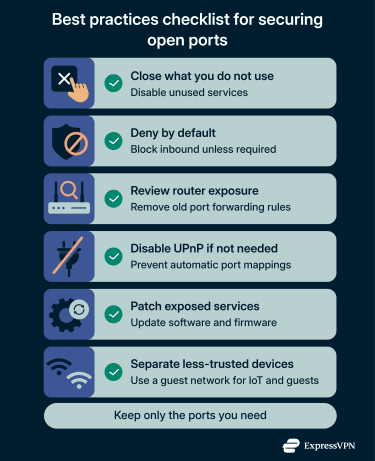

To reduce network exposure, keep only the ports you need and limit access to them. Everything else should be closed, filtered, or restricted.

Fundamental best practices

- Close unused services: If you don’t use a service, stop it by disabling it in your OS settings. This removes its listening port entirely.

- Use a “deny-by-default” firewall: Configure your firewall to block all inbound traffic, except for the specific services or ports that you allow. This reduces the risk of unauthorized access from unsolicited inbound attempts.

- Review router port forwarding: Remove any unused forwards, such as for an old game server. This is one of the most common ways a home device becomes internet-facing. Also, avoid port-forwarding sensitive services.

- Disable UPnP where possible: Disable UPnP on your router. If you need a port open for a game or server, set it up manually via port forwarding.

- Lock down router admin access: Most “mystery open ports” on home networks trace back to the router. Use a strong admin password (never the default), install firmware updates promptly, and disable remote management unless necessary.

- Segment your network: Keep smart devices and guest traffic separate from work and personal systems, for example, by using a guest network or virtual LAN (VLAN). So, for example, if an attacker gains access to a smart home device, network segmentation means they can’t reach more sensitive devices, such as your work laptop or personal files.

- Keep services patched: If a service must stay reachable, patching is not optional. Vulnerability fixes are core to preventing compromises.

Prioritize securing ports tied to remote admin and file-sharing services, then investigate anything you don’t recognize.

Advanced security measures

If you need to keep ports open for certain services, add additional safeguards so only the right people can access them.

- Limit who can connect: Where possible, only allow connections from known IP addresses (for example, your office network). Avoid making admin pages publicly reachable, such as a router login page, a server control panel, or a database dashboard.

- Use strong authentication: Turn on MFA for remote access services that support it. If you need Remote Desktop, avoid exposing it directly to the internet. A private tunnel, such as a VPN or zero trust network access (ZTNA), is usually safer than leaving an RDP port publicly reachable.

- Block high-risk services at the perimeter: If a service is not meant to be public, block it at the network boundary. For example, SMB (TCP 445) should almost never be internet-facing.

- Monitor and log access: Logging helps you spot suspicious patterns early, such as repeated login attempts, a burst of connections to the same port, or access at unusual times. Even basic router or firewall logs can help you detect brute-force attempts before they escalate into an account takeover.

Modern security approaches increasingly follow a zero-trust mindset, where access isn’t trusted just because something is on the same network. Instead, connections are verified and limited to what is necessary, reinforcing the importance of reducing unnecessary exposure and open ports.

Protecting your network with a VPN

A VPN helps protect your network traffic by encrypting the data your device sends and receives. This is especially useful on public Wi-Fi, where other users on the same network could otherwise intercept or tamper with unprotected connections. By creating an encrypted tunnel, a VPN makes it much harder for third parties to monitor your activity or interfere with your traffic.

At home, a VPN can also add a layer of privacy by masking your real IP address from the wider internet. This can reduce exposure to casual scanning and make it harder for external parties to directly identify or target your device based on its IP.

That said, a VPN doesn’t change how your local network is configured. If a port is open because of router settings, port forwarding, or an exposed service, a VPN won’t close it or fix underlying security issues. That’s why it’s still important to review router rules, close unused ports, and properly secure any services that need to be accessible from the internet.

FAQ: Common questions about open ports

What does it mean if a port is open?

An open port means a specific app or service on a device is actively listening for connections. A port can be “open” locally but still not reachable from the internet if a firewall or router is blocking inbound traffic.

Why are open ports a security risk?

Open ports widen your network exposure because they give attackers something to probe. If a reachable service is misconfigured, weakly protected, or unpatched, that open port can become a path for attackers to exploit.

What is an example of an open port?

A common example is a web server listening on port 443 for HTTPS traffic. Others include Secure Shell (SSH) on port 22 for remote administration or Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) on port 3389 for remote access. Port assignments and service names are maintained through the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority’s (IANA’s) registry.

What is an open port on public Wi-Fi?

As on any network, an open port is a service listening for connections. The difference is who can reach it. On home Wi-Fi, your router settings and firewalls generally determine whether an open port is reachable from outside. On public Wi-Fi, other people on the network may try to connect, increasing the risk.

How do I check open ports?

To see what is listening on your device, use local command tools like netstat, lsof, or ss. To determine what’s reachable over a network, a scanner is more appropriate. Nmap is widely used, and its results (open, closed, filtered, and related states) help you interpret whether a firewall configuration is blocking visibility.

How can I secure open ports effectively?

A strong baseline is “deny by default”: Block all inbound traffic, except what you actively need. Then keep services patched and properly configured, disable Universal Plug and Play (UPnP), and restrict access.

What are the common misconceptions about open ports?

Here are some common misconceptions about open ports:

- An open port is automatically dangerous: Not always. Risk depends on whether the port is reachable and whether the service behind it is secure.

- If I close the port, I’m safe: Closing unused ports helps, but exposed services also need patching, strong authentication, and sensible firewall rules.

- Attackers only target rare ports: Scanning for common services is a standard discovery technique used by attackers.

- Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) is harmless if I never touch it: UPnP can create port mappings automatically, exposing services you did not explicitly set up, so it is worth reviewing and disabling.

Can a VPN help protect me if I have open ports?

A VPN is not a fix for unsecured services, and it doesn’t “secure” a risky port. You still need to close what you don’t need and harden what you keep open. A VPN helps protect your traffic on untrusted networks by encrypting it. Instead of exposing a sensitive service, you can often access it through a VPN tunnel, which reduces your overall risk exposure.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN