How to identify and prevent a whaling attack

Whaling attacks usually blend into real business processes, asking you for a quick approval or help with a confidential work task. Often, nothing about it looks especially unusual. The pressure is subtle, but intentional, and it’s often enough to get someone to act before stopping to verify. This article looks at how whaling attacks work, how they differ from other phishing attempts, and the practical steps organizations can take to reduce risk.

What is a whaling attack?

A whaling attack is a highly-targeted phishing attack aimed at high-ranking individuals within an organization. The term “whaling” comes from the idea of targeting “big fish." Rather than going after large numbers of employees, attackers aim for people whose approval or access can have a much bigger impact.

Who do whaling attacks target?

Whaling attacks primarily target senior executives and high-level decision-makers within an organization. Common targets include:

- Chief Executive Officers (CEOs)

- Chief Financial Officers (CFOs)

- Chief Operating Officers (COOs)

- Other C-suite executives

- Senior directors and executive leadership

- Board members and senior advisors

What do attackers try to obtain?

The goal of a whaling attack depends on the situation, but it usually involves one or more of the following:

- Fraudulent financial authorization: Approval of wire transfers, payments, or invoices that usually result in direct financial loss.

- Sensitive corporate information: Access to confidential business data such as financial reports, strategic plans, or merger and acquisition details.

- Bypassing security controls: Executive approval to override standard security procedures or internal controls.

- Executive account credentials: Login details for high-level accounts that allow attackers to impersonate leadership or escalate attacks.

- Legal or regulatory information: Confidential legal documents or communications that could be exploited for financial or reputational gain.

In many cases, the attacker only needs one successful response to enable further internet fraud. A single approval, transfer, or disclosure can be enough to cause significant damage.

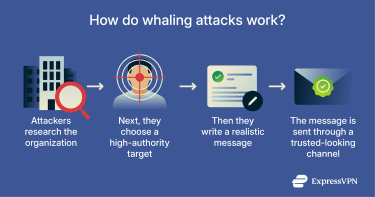

How whaling attacks work

Whaling attacks work through personalization. The process begins with attackers gathering information that is already publicly available. Organizations routinely publish details about their leadership, governance structure, and business activities through company websites, press releases, regulatory filings, and media coverage. From this information, attackers can identify who holds decision-making authority and understand the kinds of responsibilities associated with executive roles.

Using this understanding, attackers prepare communications that reflect situations executives commonly encounter in their day-to-day work. Senior leaders are typically accustomed to receiving requests that are time-sensitive, confidential, and brief, often without extensive background explanation.

Attackers typically deliver these messages through familiar business channels, usually email, and present them as coming from trusted internal or external sources. The message often emphasizes urgency, confidentiality, or executive authority. The goal is to get the target to approve a transfer, share information, or grant access before confirming the request through a separate channel.

Common tactics used in whaling

In whaling attacks, attackers use a small set of recurring tactics designed to take advantage of authority, trust, and time pressure at the executive level.

- Leaning on authority: The message claims to come from a senior leader, so the request feels hard to question.

- Adding urgency or secrecy: The sender pushes for speed, privacy, or both, so the target doesn’t loop in colleagues or slow down to confirm.

- Pushing around process: The request frames normal checks as unnecessary or asks the victim to do it “just this once,” especially for payments, approvals, or sensitive actions.

- Sounding familiar: The wording and tone match everyday business communication, so nothing immediately stands out.

- Escalating if there’s no response: If the victim doesn’t respond, the sender follows up or switches channels (for example, from email to a call) to keep the pressure on.

How is whaling different from other phishing types?

Whaling differs from other phishing attacks mainly in who is targeted, how personalized the attack is, and what the attacker hopes to achieve.

| Type | Primary target | How it works |

| Phishing | Large groups | Sends the same or similar messages at scale |

| Spear phishing | Specific individuals or teams | Tailors messages using personal or organizational details |

| Whaling | Senior or high-authority roles | Targets named individuals and uses authority and business context to encourage action |

| Vishing | Individuals or organizations | Uses phone calls or voice messages |

| Smishing | Individuals or organizations | Uses SMS or messaging apps |

Whaling vs. phishing

Unlike whaling attacks, traditional phishing usually lacks personalization and relies on volume rather than precision. Attackers send the same or similar messages to many people, often with little personalization, and rely on scale to get results. These messages commonly include links to malicious websites, fake login pages, or attachments so they can steal credentials or deliver malware.

Whaling vs. spear phishing

Whaling attacks are a form of spear phishing, which is a phishing tactic where attackers target specific individuals or groups, often using personalized information to make deceptive messages more convincing. The main difference is that spear phishing doesn’t necessarily target high-level executives: targets can include individuals or teams with access, such as employees in finance, HR, or IT roles.

Whaling vs. vishing

Vishing attacks rely on phone calls or voice messages rather than written communication. Attackers often pretend to be trusted people, such as executives, vendors, or service providers, so the target doesn’t second-guess them. The interaction happens in real time, which also means it’s easier for them to push for quick decisions and put the victim under pressure. Whaling attacks usually start with written messages, most often email, but they can move to phone calls later on.

Whaling vs. smishing

Smishing attacks use SMS or messaging apps, such as text messages or chat platforms, to deliver phishing messages. These attacks often try to catch people off guard with short, direct prompts that push them to act quickly. In whaling, messaging apps tend to come into play later, after an attacker has made initial contact via email.

Common types of whaling attacks

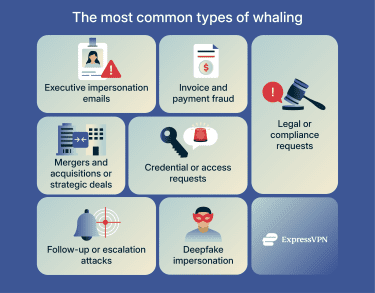

Whaling attacks often show up in recurring business scenarios, but it can depend on which role the attacker wants to target and the type of action they’re after. Common types include:

- Executive impersonation emails: Attackers pretend to be a CEO, CFO, or other senior leader and send messages that push for urgent action, often marked as confidential or time-sensitive.

- Invoice and payment fraud: Attackers ask for wire transfers, invoice payments, or bank detail changes, presenting them as routine finance tasks that need quick approval.

- Legal or compliance requests: Attackers pose as legal or compliance teams and frame messages around audits, reviews, or regulatory issues, using formal language to discourage questions.

- Mergers and acquisitions or strategic deals: Attackers link requests to acquisitions, partnerships, or other high-level negotiations and stress secrecy or limited disclosure.

- Credential or access requests: Attackers try to get executives to share login details or approve access to systems or documents, which can increase the risk of identity theft and fraud.

- Deepfake impersonation in meetings: In some cases, attackers use synthetic audio or video to impersonate executives during calls or meetings, which can make them seem believable.

Signs of a whaling attack

The warning signs of whaling attacks tend to show up in how the messages are framed. Pay closer attention if you notice patterns like these:

- A routine request that suddenly feels rushed: The task itself looks normal, but the timing or tone pushes you to act immediately instead of following your usual checks.

- Unusual emphasis on secrecy: The message stresses confidentiality or asks you not to involve others, even though the request affects money, access, or approvals.

- Little or no room to verify: The request makes it feel awkward or inappropriate to confirm details through your normal process.

- High-impact actions: You’re asked to move money, share sensitive information, or approve access in a way that would be hard to undo.

- Requests that don’t match normal process: The message asks you to skip steps you’d usually follow, or frames the situation as a one-off exception.

- Small details that don’t quite line up: This could include a slightly altered sender address, wording that feels off, or messages arriving at unusual times.

- Pressure that increases if you pause: If you don’t respond right away, you get follow-up messages to push urgency or reinforce the request.

- Attempts to change how you communicate: You’re asked to move the conversation to a call, text, or messaging app, which can make verification harder.

Real-life examples of whaling attacks

Incidents of executive-level impersonation have been widely reported in the media, highlighting how these scams can affect even well-resourced global organizations. Examples include:

- Banking executive impersonation: Attackers posed as senior executives and persuaded internal staff to approve several high-value transfers. The activity went undetected until an internal review identified the fraud, which resulted in losses totaling tens of millions of euros and triggered a formal investigation.

- Executive-style email fraud: Media reports have described incidents in which finance personnel at multinational companies received emails appearing to come from senior leadership, requesting urgent international transfers as part of business transactions. In one case, a large payment was initiated before the organization later discovered the message had been sent by impersonators rather than the executive it claimed to be from.

- Vendor impersonation: Law enforcement investigations have uncovered large-scale invoicing fraud schemes where attackers posed as legitimate suppliers to well-known global firms. Employees received payment requests that appeared routine and business-related, resulting in significant unauthorized transfers before the fraud activity was exposed.

How to protect yourself from whaling attacks

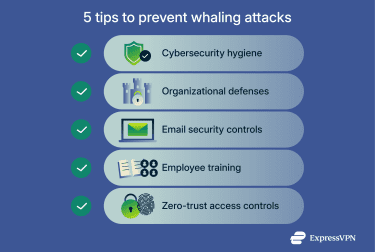

No single control can entirely prevent whaling attacks. To help protect your systems, a combination of basic security practices, technical defenses, and clear awareness and training is required.

Practice good cybersecurity hygiene

Strong cybersecurity reduces the risk that attackers can exploit accounts or communication channels during a whaling attack. Although these measures can’t prevent social engineering itself, they limit the damage by making account compromise and impersonation more difficult. Key measures include:

- Using strong, unique passwords and multi-factor authentication (MFA) on email and other sensitive accounts.

- Limiting access to shared inboxes, financial systems, and approval tools to only those who need them.

- Monitoring for unusual login activity or access attempts.

- Keeping devices and software up to date to reduce avoidable risks.

- Protecting connections when working on public or shared networks, including the use of a virtual private network (VPN) to secure internet traffic.

- Preparing and testing an incident response plan so teams know how to recognize, contain, report, and recover from suspected whaling attempts.

Implement organizational defenses

Clear internal processes can help stop a single message from triggering a costly mistake. When people know what steps to follow and feel expected to follow them, they’re less likely to rush or bypass checks under pressure. Effective organizational defenses often include:

- Clear approval and verification processes: Set defined steps for handling payments and sensitive data requests, especially when they come with urgency.

- Separation of duties: Make sure no one person can approve high-risk actions on their own.

- Verify requests through a separate channel: Confirm executive or urgent requests through a separate, trusted channel, such as a known phone number, rather than replying to the original message.

- Documented escalation paths: Clearly explain who to contact and what to do when a request feels unusual or doesn’t quite add up.

Install technical protections (DMARC, SPF, DKIM, email filtering)

Technical email protections help reduce some common forms of impersonation, especially when attackers try to spoof an organization’s email domain. These controls work behind the scenes and help email systems decide whether a message is likely to be legitimate. Common protections include:

- Sender Policy Framework (SPF): SPF lets receiving email servers check whether a message claiming to come from your domain was sent from an approved server. If it wasn’t, the server can flag or reject the message, which helps prevent basic domain spoofing.

- DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM): DKIM adds a digital signature to outgoing emails. The receiving server uses this signature to verify that the message hasn’t been altered in transit and that it really came from the stated domain.

- Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance (DMARC): DMARC builds on SPF and DKIM by telling receiving servers what to do when an email fails those checks, such as quarantining or rejecting it, so that the email doesn’t reach your inbox. It also provides reports that show how your domain is being used or misused in email.

- Email filtering and impersonation detection: Email security tools can flag messages that show signs of impersonation, such as look-alike domains, unusual sender behavior, or patterns commonly linked to executive fraud.

These controls can block or flag many spoofed emails, but they don’t stop every whaling attack. Messages sent from compromised accounts or carefully written impersonation attempts can still reach inboxes, which is why technical protections work best alongside clear processes and training.

Organize training for executives and senior leaders

Training should focus on helping executives and senior decision-makers recognize and stop whaling attacks, because these attacks specifically target authority, trust, and time pressure at the leadership level.

Effective training should teach executives to take a second look at requests that appear urgent, confidential, or tied to executive authority. They should also always suspect a request that bypasses established processes or relies on seniority to discourage verification. Finally, executives should feel comfortable confirming unusual requests through separate channels and involving appropriate teams before approving high-impact actions.

Use zero-trust practices

Zero-trust practices control system access based on identity, role, and context, rather than assuming that every request or person is trustworthy by default. In practice, this means limiting what executives and staff can do within systems unless they actually need that level of access. Even senior roles don’t always need unrestricted access to financial systems, sensitive data, or approval tools.

Zero trust also helps contain damage if an account is compromised. You can restrict access to only what’s necessary, which helps reduce how far an attacker can move inside your systems instead of giving them free rein.

What to do if you suspect a whaling attack

If something about a request feels off, acting quickly and methodically can help limit potential damage. Here are some immediate steps to take:

- Pause before acting on the request: Don’t rush to complete the task, even if the message stresses urgency or confidentiality. Whaling attacks rely on quick decisions made under pressure.

- Don’t reply directly to the message or click links: Responding to the same email or message can keep you inside the attacker’s channel, so avoid clicking any links or opening attachments until you can verify the request.

- Verify the request through a separate, trusted channel: Confirm the request using known contact details, such as a phone number or email address you already have on record. Don’t use the contact information provided in the message itself.

- Flag the message internally: Notify the appropriate internal teams, such as IT, security, finance, or compliance, so they can review the message and check whether similar attempts are affecting others.

- Preserve the message and related details: Keep copies of the email, headers, attachments, and any related communication to help with internal investigation.

- Escalate immediately if action was already taken: If you sent money or shared information, report it right away. Early escalation improves the chances of limiting financial loss or stopping further misuse.

Reporting the attack to authorities

It's a good idea to report a whaling attack even if you didn’t lose money or share data. Individual reports help authorities identify patterns, track active campaigns, and warn other organizations about similar threats. If you’ve lost money, disclosed sensitive business or personal information, or received an impersonation request that could affect your reputation, reporting early can also support recovery efforts or insurance claims.

If you’re in the U.S., you can report whaling and related phishing attacks to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3). If you’re in the U.K., you can report incidents through Report Fraud, the national fraud and cybercrime reporting service.

FAQ: Common questions about whaling attacks

What is a whaling attack?

A whaling attack is a targeted phishing scam aimed at senior or high-authority individuals. Attackers tailor messages to match real business situations and try to prompt quick action, such as approving a payment or sharing sensitive information.

How is whaling different from phishing?

Phishing targets a large number of people with generic messages. Whaling targets specific individuals and relies on authority, context, and personalization rather than scale.

Who do whaling attackers usually target?

Attackers usually target executives and other high-authority roles, such as finance, legal, or senior management positions. They focus on influence and decision-making power, not technical access.

What are common signs of whaling?

Common signs of whaling include urgent or confidential requests, pressure to act quickly, attempts to bypass normal approval steps, requests involving money or sensitive data, and subtle inconsistencies in sender details or timing.

How can companies protect themselves from whaling attacks?

Companies can reduce the risk of whaling attacks by combining clear approval processes, employee training, email security controls, access restrictions, and regular verification practices. No single tool prevents whaling on its own.

What should I do if I receive a suspicious message?

If you receive a suspicious message, the most important thing to do is pause before acting. There are also some other key steps to take. Don’t reply directly to the message or click links. Verify the request through a separate, trusted channel and report it internally so it can be reviewed.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN