What is MyDoom? A comprehensive guide to the infamous worm

In January 2004, a computer worm called MyDoom began spreading through email inboxes worldwide. Within two days, the worm was already circulating in 168 countries.

MyDoom didn’t rely on advanced hacking techniques or software flaws. It worked by tricking people into opening email attachments that looked completely normal: delivery errors, system notifications, and routine messages. In 2004, opening these kinds of attachments was just part of using email.

This article explains what MyDoom was, how it worked, why it spread so fast, and what it still teaches us about email security today.

What is MyDoom?

MyDoom was a mass-mailing computer worm discovered on January 26, 2004. It became one of the fastest-spreading pieces of malware in the history of the internet, overwhelming mail servers and disrupting organizations worldwide within hours of its release.

Although it’s often called a virus, MyDoom didn’t destroy files or corrupt data. MyDoom was a worm. It replicated itself endlessly, using email as its delivery system and relying on people opening infected email attachments rather than exploiting software vulnerabilities.

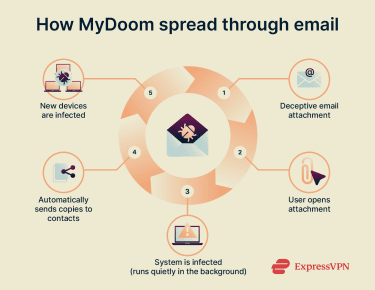

Once someone opened the attachment, MyDoom silently harvested email addresses from their computer and automatically started sending copies of itself to new victims. This automated, self-replicating design let it scale at unprecedented speed.

Two main variants of the worm circulated widely. The first version, MyDoom.A, used infected computers to launch a large-scale distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack against the U.S. software company the SCO Group. The attack knocked its website offline for days.

The second version, MyDoom.B, targeted Microsoft. The company took preemptive defensive measures that reduced the impact, but the incident still highlighted how large organizations could be targeted by coordinated botnet-style attacks.

How MyDoom worked

MyDoom’s effectiveness came from simplicity. It didn’t use advanced exploits or complex code obfuscation. Instead, it relied on predictable user behavior and basic system functions.

Once a single machine was infected, the worm could operate independently, sending out new copies of itself without any input from its creator.

The worm primarily targeted Windows-based operating systems, which dominated personal and workplace computing at the time, further amplifying its reach.

Deceptive emails and attachments

MyDoom spread through emails designed to look like system notifications or delivery error messages. Common subject lines included “Error,” “Mail Delivery System,” “Hello,” and “Test.” The messages inside the emails were equally generic.

When someone opened the attachment (usually a .zip, .scr, or .pif file), the malware activated quietly in the background without obvious warnings or disruptions. Once running, the worm scanned address books, files, and drives for email addresses. It then automatically sent copies of itself to new recipients, repeating the cycle.

Unauthorized remote access

After infecting a system, MyDoom installed a backdoor that opened specific Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) ports (3127–3198, depending on the variant). This allowed attackers to control the computer remotely without the owner knowing.

Each infected machine on its own had limited impact. However, as infections multiplied, these machines linked together into a botnet: a huge network of compromised computers that could be directed to perform coordinated attacks.

Coordinated DDoS attacks

The two main worm variants were programmed to launch timed attacks against the SCO Group’s and Microsoft’s websites.

The attacks showed how email worms could be weaponized beyond simply propagating. The same infected machines that were spreading the worm could also take part in targeted attacks against specific organizations.

Peer-to-peer network spread

Some versions of MyDoom attempted to spread through peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing networks, like Kazaa, which were popular in the early 2000s. The worm would copy itself into shared folders with enticing filenames, hoping users would download and open the files.

However, email was the main and most effective distribution method.

Why MyDoom was so effective

MyDoom worked because it fit perfectly into how people used the internet in 2004. It didn’t ask users to do anything unusual. Everyday habits, combined with limited security infrastructure, gave the worm exactly what it needed to move fast.

Email as a trusted delivery channel

In the early 2000s, email attachments were a normal part of daily communication. People often used them to share documents, photos, and software, both at work and at home. Opening attachments rarely raised suspicion, making it easy for MyDoom to blend in and spread unnoticed.

High trust in system-looking messages

Most users trusted messages that looked technical and routine. MyDoom exploited this by mimicking delivery errors or system notifications. If a message seemed to come from a familiar source or an automated system, people were far more likely to open it without hesitation.

There was also less general awareness about email-based threats. The concept of phishing was still relatively new, and many users hadn’t yet developed the skepticism that’s more common today.

Limited defenses and fragile infrastructure

In 2004, email filtering was basic, antivirus tools were reactive, and internet infrastructure had far less capacity than it does today. This meant a sudden surge of automated emails was enough to strain not only individual inboxes but also entire network segments and internet service providers (ISPs).

What damage did MyDoom cause?

Unlike modern malware strains, MyDoom didn’t cause damage through stealing data or destroying files. Its impact came from widespread disruption, network congestion, and the cost of responding to an outbreak that spread faster than defenses could adapt.

Individual and organizational impact

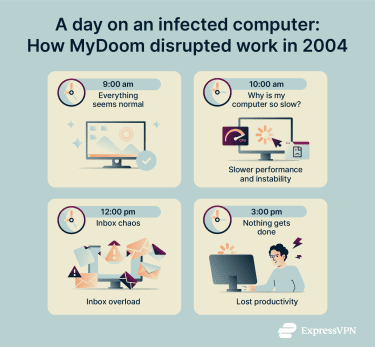

For users and organizations, a MyDoom infection made systems difficult to use rather than destructive.

- Slower performance and instability: Infected machines constantly sent emails in the background, consuming processing power and memory. This often resulted in sluggish performance, unresponsive applications, and system freezes.

- Severely congested email inboxes: Users were not only sending out huge volumes of infected messages; they were also receiving large quantities of automated replies and failed delivery notices. Inboxes quickly became filled with junk, making legitimate communication difficult.

- Lost productivity: MyDoom’s real cost at the individual level was lost time. Employees struggled to work on slow or unstable systems, while IT teams spent hours isolating infected machines and restoring basic functionality.

Wider internet and economic impact

The effects of MyDoom went well beyond individual machines.

At its peak, MyDoom was responsible for up to 30% of all email traffic worldwide, according to contemporary reports. This sudden surge placed enormous strain on email servers, ISPs, and network infrastructure, contributing to noticeable slowdowns across parts of the internet.

Estimates at the time put MyDoom’s total economic impact at around $38 billion, largely due to downtime, cleanup efforts, and lost productivity rather than direct financial theft. Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $66.5 billion today, which helps explain why MyDoom is often described as one of the most costly malware outbreaks in history.

Is MyDoom still active?

MyDoom is no longer an active threat. It doesn’t spread in modern environments the way it did in 2004. However, its name still occasionally crops up in security reports.

There are a few reasons why this happens:

- Legacy systems: Some older machines running outdated operating systems may not have been fully cleaned. These systems may still attempt to send MyDoom-related traffic. Modern networks block these attempts immediately, but the activity is still recorded.

- Research and testing environments: Cybersecurity teams and antivirus companies keep old malware samples to study threat behavior and improve defenses.

- Reused code or signatures: Over the years, other malware authors have borrowed parts of MyDoom's highly efficient replication engine. When security tools detect similar behavioral patterns or code signatures, they may report a MyDoom detection, even if the underlying threat is actually a newer, different malware variant.

- Old email archives and backups: Scanning old attachments can trigger detections from today’s antivirus solutions, even though the malware can’t execute on modern systems.

MyDoom’s influence on modern security

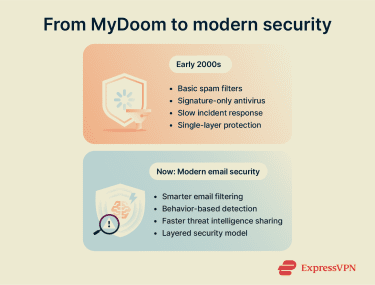

MyDoom, along with other major outbreaks of the early 2000s, such as the ILOVEYOU worm and Sobig, forced significant changes in how email security works.

- Better email filtering: Email systems evolved to stop suspicious messages earlier in the delivery process. Modern spam filters, attachment scanning, and content analysis prevent many dangerous emails from ever reaching the inbox.

- Behavior-based detection: Security software began monitoring for unusual behavior patterns, not just known virus signatures. This makes it possible to catch new threats as they emerge, rather than waiting for specific malware to be identified and cataloged.

- Faster threat intelligence sharing: Organizations and security companies now share threat information in near real-time through coordinated response networks. This prevents one infection from becoming a global problem and allows defenses to update quickly as new threats appear.

- Multi-layered defense strategies: The security industry moved away from relying on any single defense measure. Modern approaches combine email filtering, endpoint protection, network monitoring, user training, and incident response planning.

What we can learn from MyDoom

MyDoom showed that cyberattacks don’t need to be technically sophisticated to succeed. Familiarity and automation were enough. More than two decades later, email is still one of the most common attack vectors, as it targets human behavior rather than software vulnerabilities or misconfigured systems.

MyDoom succeeded because it relied on everyday user behavior. No vulnerability had to be discovered, no complex code had to be written; just a message that looked ordinary enough to open.

Knowing common phishing red flags and signs of malware plays a key role in improving your email security:

- Scrutinize unexpected attachments, even “routine” ones.

- Verify the sender by checking the actual email address, not just the display name.

- Pause before acting, especially if the message creates urgency.

- Check links by hovering over them to preview the actual destination before clicking.

Good security habits are most effective when supported by the right tools. Modern anti-malware software doesn’t just look for known malicious files; it watches for suspicious behavior. If a program suddenly tries to harvest your contacts and open a hidden port, your security software will stop the process instantly.

To get the best out of these tools, use them together with regular software updates, strong passwords, and a healthy skepticism about unexpected communications.

FAQ: Common questions about MyDoom

What is the origin of MyDoom?

MyDoom appeared on January 26, 2004, as a mass-mailing worm designed to spread through everyday email use. The worm quickly stood out because of how fast it spread across inboxes worldwide.

Who stopped the MyDoom virus?

No single entity stopped MyDoom. The threat faded over time as email providers, antivirus companies, and organizations improved their security measures. Better filtering, improved detection, patched systems, and greater user awareness made it harder for the worm to spread. The programmed distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks also had built-in expiration dates, after which they stopped automatically.

Which is the most expensive computer virus in the world?

MyDoom is often associated with damage estimates of over $38 billion. Although it’s commonly called a virus, it was technically a mass-mailing worm. The costs came mainly from overloaded email systems, lost productivity, cleanup efforts, widespread network slowdowns, and business disruptions.

How did MyDoom spread?

MyDoom spread mainly through email attachments that appeared to be routine delivery errors or system messages, with subject lines like “Error,” “Mail Delivery System,” “Hello,” and “Test.” When someone opened the attachment, the worm activated and sent copies of itself to email addresses it found on the infected computer.

Some variants also tried to spread through peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing networks, like Kazaa, though email was the main distribution method.

Are modern threats influenced by MyDoom?

Yes. While modern malware is more technically advanced, many email-based attacks still rely on the same principle MyDoom followed: using email to exploit trust and routine behavior.

How can malware be avoided?

Simple habits significantly reduce risk. Be cautious with unexpected email attachments, even those that seem routine. Verify the sender by checking the actual email address, not just the display name. Be skeptical of messages that create urgency or pressure you to act quickly. Keep your operating system and software updated with the latest security patches. Use reputable antivirus software and keep it current.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN