What is encrypted SNI, and why does it matter for your privacy?

When you visit a website today, your browser usually connects using Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) automatically, meaning the information exchanged between your device and the website is encrypted by default. This built-in encryption is what protects things like logins, messages, and payment details from being read by anyone watching the network.

But even with HTTPS, some connection details can still be exposed during the initial setup, including the website name you’re trying to reach. That’s the privacy gap that encrypted Server Name Indication (ESNI) was designed to fix. This guide explains what ESNI is and how it works.

What is ESNI?

ESNI is a privacy feature that hides the website name your browser requests when starting an HTTPS connection.

When you want to visit a site, your browser first needs to connect to the web server hosting it, and that connection is protected by Transport Layer Security (TLS), which is the encryption system that HTTPS relies on to keep the data private. During this setup step, the browser and server agree on encryption settings and establish secure keys so that anything sent afterward can’t be read by outsiders.

However, before encryption is fully in place, the browser typically includes the site’s domain name using Server Name Indication (SNI) so the server knows which website you’re trying to reach. Traditional SNI is sent in plaintext, which means this hostname is readable to anyone monitoring the connection. ESNI prevents that from happening.

What is SNI?

SNI is an extension to the TLS protocol that lets a client (like your browser) tell the server which hostname it wants to connect to at the very start of the connection, like news.example.com vs. shop.example.com.

The reason this feature exists is simple: one server can host multiple HTTPS sites on the same IP address. An IP address can get your browser to the right server, but it doesn’t say which website on that server you want. SNI fills in that missing detail so the server can present the correct TLS certificate for that specific hostname and avoid certificate-mismatch errors.

Why was ESNI introduced in TLS 1.3?

TLS 1.3 (finalized in 2018) brought many security and privacy improvements to HTTPS. Notably, TLS 1.3 encrypts more of the connection setup process than previous versions: for example, the server’s certificate is now encrypted by default. However, the SNI remained exposed in TLS 1.3 handshakes, representing a significant privacy vulnerability.

Encrypted SNI was developed to close that gap and improve privacy.

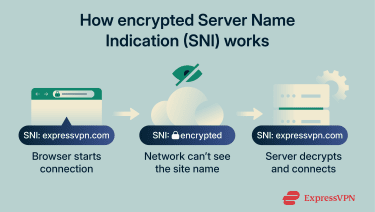

How encrypted SNI works

To understand how ESNI works, we have to break down the TLS handshake to see where the hostname appears, and then how ESNI hides it.

The TLS handshake process explained

Before your browser can securely load a website over HTTPS, it has to establish a TLS connection with the server. This setup phase is called the TLS handshake, and it’s where the browser and server agree on the security settings for the session.

In simple terms, the handshake is responsible for confirming you’re connecting to the right server, choosing encryption methods that both sides support, and creating shared encryption keys for the session. Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of a TLS 1.3 handshake:

- ClientHello: Your browser starts the connection by sending a ClientHello. It proposes security options (like supported cipher suites) and includes TLS extensions, often including SNI, which contains the hostname the browser wants to reach. At this point, the message is not fully encrypted yet, so SNI can be visible.

- ServerHello: The server replies with a ServerHello confirming the chosen parameters and providing the information needed to proceed. In TLS 1.3, the key agreement happens as part of this early exchange, which allows encryption keys to be established immediately after the ServerHello.

- Handshake encryption begins: Once those keys are established, the rest of the connection setup messages are encrypted. This includes the server’s authentication material (like the certificate) and other handshake details.

- Finished messages: The server sends an encrypted “Finished” message to prove it has the correct keys; the client replies with its own encrypted “Finished.” This confirms both sides agree on the session keys and that the setup hasn’t been tampered with.

- Secure connection established: The browser can now send the actual web request, and the server responds, both inside an encrypted TLS channel.

How encryption protects the SNI field

ESNI protects SNI by encrypting the hostname before it’s sent in the ClientHello. Instead of sending the real domain name in plaintext, the browser first retrieves the site’s ESNI public key, typically via the Domain Name System (DNS), and uses it to encrypt the SNI value.

Only the destination server, which holds the matching private key, can decrypt it and recover the hostname. Anyone else observing the connection can still see that a TLS handshake is happening, but they can’t directly read the hostname from SNI anymore, which prevents straightforward site identification based on SNI alone.

Encrypted SNI vs. traditional SNI: Key differences

| Traditional SNI | Encrypted SNI | |

| Primary goal | Enables the server to host multiple HTTPS domains on the same IP address | Preserves SNI functionality while improving privacy during connection setup |

| Deployment status | Widely supported across browsers, servers, and networks | Partial adoption; depends on browser support and correct server configuration |

| Operational complexity | Simple and mature | More complex, often requiring DNS support and hosting integration |

| Compatibility with middleboxes | Generally compatible with enterprise firewalls and inspection tools | Can break or be blocked in networks that rely on hostname visibility |

| Filtering impact | Easier for networks to filter traffic by domain | Makes domain-based filtering harder without deeper traffic analysis |

Encrypted Client Hello (ECH): The successor to ESNI

ECH is the modern replacement for ESNI. The reason ESNI needed a replacement is that the website name, which ESNI hides, isn’t the only sensitive detail that can leak during connection setup. ECH was introduced to protect a larger portion of that initial connection information: it encrypts most of the ClientHello (including the server name).

How ECH improves privacy and metadata protection

For ECH to work, the browser needs the site’s ECH configuration in advance, including the public key used to encrypt the hidden portion of the ClientHello. Websites publish this configuration in DNS, the same system your browser uses to look up a website’s IP address.

With ECH, DNS can also return an extra piece of information: an HTTPS record that tells the browser “this site supports ECH” and provides the public key details needed to encrypt the inner ClientHello before the connection begins.

Once the browser retrieves it, it creates two layers:

- Outer ClientHello: a minimal, public message that allows the connection to be routed

- Inner ClientHello: an encrypted message containing the real hostname and other sensitive parameters

The server decrypts the inner ClientHello and continues the connection normally. That means someone watching the connection can see that a TLS handshake is happening, but they have a much harder time learning which specific site is being requested from the handshake itself. If the browser can’t retrieve the ECH configuration or the server doesn’t support it, the connection falls back to a standard TLS handshake.

Browser, OS, and server support for ECH

ECH only works when all required pieces are in place at the same time: your browser has to support it, the website has to be configured for it, and your browser must be able to retrieve the site’s ECH configuration from DNS. Because that’s a lot of moving parts, it’s completely normal to use an “ECH-capable” browser and still rarely connect using ECH, as most websites simply haven’t enabled it yet.

Popular browsers (what to expect today)

Chrome (and Chromium-based browsers), Edge, and Firefox support ECH. Safari has indicated support, but it hasn’t implemented ECH yet.

| Web browser | ECH support in practice |

| Chrome | Supported (gradual rollout; site must enable ECH) |

| Edge | Supported (site must enable ECH) |

| Firefox | Supported (enabled by default in Firefox 119+) |

| Safari | Not available in stable Safari yet |

| Opera, Brave, Vivaldi, Samsung Internet | Usually follows Chromium support (may vary by settings/version) |

Operating system (OS) support

On Windows, macOS, and Linux, ECH is a browser-only feature, not a system setting. If the browser has ECH built in (Chrome, Firefox, and Edge all do), it can use ECH when the website has ECH configured. If the site owner hasn’t yet enabled ECH, the web browser can’t use it and will fall back to a normal handshake.

On iOS and iPadOS, WebKit and Safari have indicated support but have not implemented ECH in shipped form. On Android, it’s closer to desktop: ECH is primarily a browser feature.

Server support (what a website has to do)

For ECH to work, the website needs a “front door” that understands it. That front door is the system that handles HTTPS connections first, often a content delivery network (CDN). A CDN is basically a network of servers that sits in front of a site and serves content from locations closer to visitors, and it often handles HTTPS connections for the site as well.

That matters because ECH hides the website name inside an encrypted part of the browser’s first message. The HTTPS front door needs to be able to decrypt that hidden part so it can route the connection to the right website and present the correct certificate. If the front door can’t decrypt it, ECH can’t be used, and the browser falls back to a normal TLS handshake.

The site must also publish a DNS HTTPS record that includes the ECH details, which are necessary for the browser to encrypt the "inner hello." If that record is missing, the browser won’t even try ECH because it doesn’t have the information needed to start.

Current adoption challenges and limitations

The reason ECH isn’t the default everywhere comes down to two separate things: adoption incentives and technical prerequisites.

Adoption friction (why many sites don’t enable it)

For most sites, the benefit isn’t always compelling. ECH is most valuable when many different websites share the same public IP address, something that commonly happens when sites are hosted behind a CDN, where one edge server handles traffic for lots of domains. If a site uses a dedicated IP that already identifies it, ECH provides less additional privacy.

ECH is also still optional. Many sites focus on performance and uptime first, and privacy features like ECH often don’t get attention unless there’s user demand or regulatory pressure. In practice, actual ECH deployment remains limited.

Technical prerequisites (what has to be in place for ECH to work)

Some hosting providers, especially CDNs like Cloudflare, make enabling ECH as easy as flipping a switch. However, that convenience depends on the platform supporting ECH end-to-end. On setups without built-in support, ECH requires a few specific pieces to be in place:

- An ECH-capable TLS endpoint: The server (or load balancer) terminating TLS must support ECH so it can decrypt the encrypted ClientHello.

- Published ECH configuration in DNS: The site must publish its ECH configuration via DNS HTTPS records, so browsers can retrieve the public key or config before connecting.

- A resolver path that can retrieve those records: Even if the site publishes the HTTPS record, ECH won’t activate if the client’s DNS resolver path doesn’t return it, and the connection will fall back.

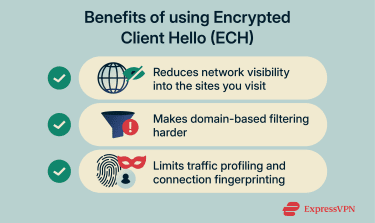

Benefits of using ESNI or ECH

Hiding the domain name during the early stage of an HTTPS connection comes with several practical benefits.

Enhancing online privacy

On a normal HTTPS connection, the content loaded (pages, messages, passwords) is encrypted between the browser and the website. This prevents people or systems with visibility into the same network from reading the actual page content just by observing traffic. However, some connection metadata can still be visible, including when a connection occurs and how much data is exchanged.

When the hostname is visible during connection setup, it can reveal the domain being requested. ECH reduces that exposure, especially when paired with encrypted DNS, because DNS lookups can otherwise reveal the same destination information. This still isn’t full invisibility: the destination IP address and traffic patterns can remain visible, but ECH meaningfully reduces what’s easy to identify at the domain level.

Reducing exposure to domain-based filtering

One common way HTTPS traffic is managed on networks is by identifying the requested domain early in the connection and applying policies based on that information. This approach relies on hostname visibility during the TLS handshake and does not require decrypting the traffic itself.

By encrypting the hostname during connection setup, ECH reduces the availability of this signal. When combined with encrypted DNS and a large CDN that supports ECH, this can significantly limit how much domain-level information is exposed at that stage of the connection.

But if any of those pieces are missing (for example, the site isn’t using ECH, DNS queries are still exposed, or the site is on a dedicated IP), then the destination can often still be identified using other signals.

Protecting against traffic profiling attacks

Even when content is encrypted, networks can still attempt to classify traffic using observable patterns and connection metadata. One example is TLS fingerprinting (often discussed as part of browser fingerprinting), where an identifier is derived from connection characteristics such as supported TLS features and extensions.

ECH doesn’t eliminate all profiling signals. Observers may still see the destination IP, timing, and some “outer” connection details that remain visible for compatibility. However, by encrypting more of the ClientHello, ECH reduces how much high-value metadata is exposed by default and narrows the amount of information available for passive profiling.

Practical implementation of ESNI and ECH

In real-world browsing, ECH either activates automatically when everything aligns or it doesn't. So “implementation” is less about flipping one switch and more about using a browser and DNS setup that can actually negotiate ECH when a site supports it.

How to enable ESNI or ECH on popular browsers

In most browsers, the goal is to ensure your browser can use ECH when a site supports it, which usually means two things. You need to keep the browser updated and enable encrypted DNS so the browser can fetch the site’s required DNS HTTPS record without leaking the same domain through plain DNS. Here’s how to do that in Chrome, Edge, and Firefox.

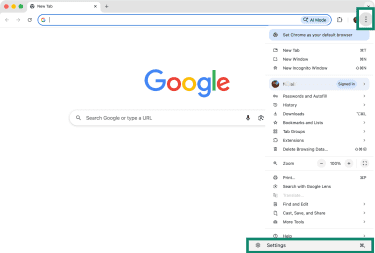

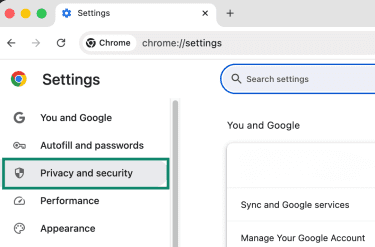

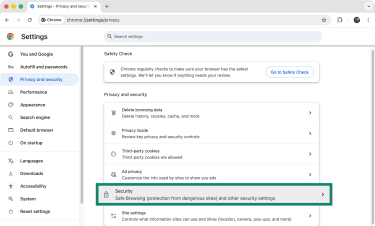

Google Chrome

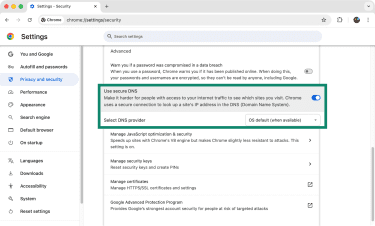

- Launch Chrome and click the three-dot button (top-right corner).

- Select Settings, and then click Privacy and security using the sidebar on the left.

- Select Security.

- Scroll down to Use secure DNS and enable that option if it’s disabled, then choose a provider from the dropdown list.

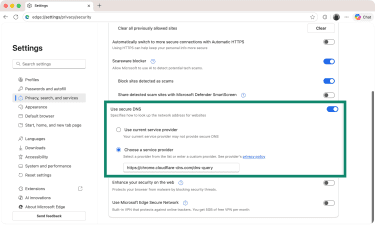

Microsoft Edge

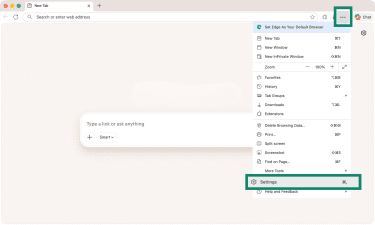

- Launch Edge and click the three-dot button (top-right corner).

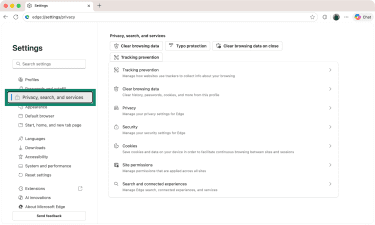

- Pick Settings, and select Privacy, search, and services on the left.

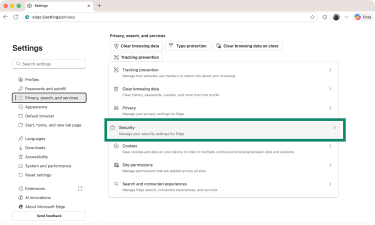

- Click Security.

- Scroll down to Use secure DNS and enable this option.

- Choose a service provider and pick your preferred DNS provider.

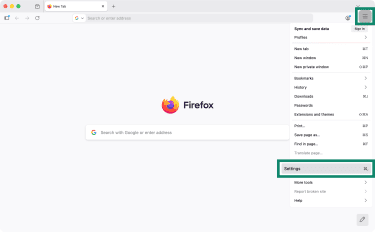

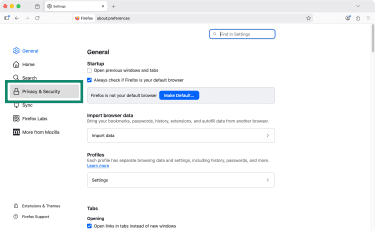

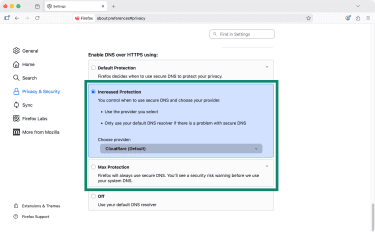

Mozilla Firefox

- Launch Firefox and click the three-line (hamburger) button (top-right corner) and select Settings.

- Click Privacy & Security.

- Scroll down to Enable DNS over HTTPS using: and choose between Increased Protection or Max Protection.

- Lastly, pick the DNS provider you wish to use from the dropdown menu.

Common issues and troubleshooting tips

If ECH isn’t active, it usually isn’t “broken.” It’s just not being used for that connection, so the browser quietly falls back to a normal TLS handshake. Here are the most common reasons, plus quick ways to narrow it down.

- You can’t “see” ECH in browser settings: ECH isn’t visible in the browser UI, so the practical way to confirm it is to use a purpose-built check page. You can use Cloudflare’s Browser Security Check, and there should be a check mark for Secure SNI.

- The website doesn’t support ECH yet: Even with an ECH-capable browser, many websites don’t yet support ECH, so it’s normal to see it off most of the time.

- Your DNS setup can stop ECH from even starting: ECH needs keys fetched via DNS using the newer HTTPS record. If DNS can’t deliver that HTTPS record reliably on your network, ECH won’t trigger. A quick check is to visit Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 help page and confirm that Using DNS over HTTPS (DoH) shows Yes.

- A work or school network may force ECH off: Firefox explicitly disables ECH when it detects trusted proxies or when parental controls are applied. That’s usually done to keep network controls working as expected.

How virtual private networks (VPNs) complement ESNI

A VPN complements ESNI and ECH by adding an encrypted tunnel between your device and the VPN server, which changes what your local network and ISP can see about your traffic overall.

Hiding browsing metadata beyond the SNI field

ECH mainly protects one potential leak: the website name (hostname) that can otherwise show up in the TLS handshake. This means that even with ECH enabled and working, anyone with network-level access can still learn a lot from the connection itself, like which IP address you’re using.

A VPN protects a bigger slice of metadata. It encrypts:

- The DNS requests your device sends, which normally reveal what domains you’re looking up.

- The destination IP addresses your device is trying to reach.

- The TLS connection setup messages, including the ClientHello/SNI/ECH traffic, as they travel across your local network and ISP.

- The actual application data, including web traffic, app traffic, and background connections.

Reducing network-level traffic visibility

Network operators can observe connection metadata, and some use deep packet inspection (DPI) to identify what kind of traffic it is; for example, whether you’re streaming video, making a voice/video call, gaming, downloading files, or using specific apps and services. A VPN limits the signals DPI relies on to classify your traffic by turning everything into one encrypted tunnel between you and the VPN server.

Protecting traffic on public and untrusted Wi-Fi networks

ESNI and ECH reduce domain exposure during HTTPS setup, but public Wi-Fi is risky for a different reason: the Wi-Fi owner controls the network you’re using. That includes the router or access point you connect to and often the DNS settings your device is told to use.

In that environment, the hotspot operator, or an attacker running a fake hotspot, can typically:

- See which devices are connected

- See your traffic metadata (destination IPs, timing, data volume)

- Control or manipulate DNS responses if DNS isn’t encrypted

- Redirect you to captive portals or block certain connections

- Attempt to interfere with non-TLS traffic or poorly secured apps

In this scenario, a VPN complements ESNI and ECH by encrypting traffic from your device to the VPN server before it crosses the Wi-Fi network. That prevents the hotspot from seeing your DNS lookups and the real destinations you connect to, and it makes DNS tampering and traffic manipulation much harder once the tunnel is established.

ESNI and ECH compared to other privacy technologies

ECH is narrow by design. Other tools protect different parts of the connection, so they’re often complementary rather than interchangeable.

- Encrypted DNS (DoH/DoT): DNS over HTTPS (DoH) and DNS over TLS (DoT) encrypt DNS lookups, which limits observers on the network from seeing which domains you’re trying to resolve. This matters because even if ECH hides the hostname in the TLS handshake, unencrypted DNS can still reveal the site you’re visiting.

- Apple iCloud Private Relay: Private Relay routes traffic through two separate relays so that no single party can see both your identity and your destination. It’s designed to reduce exposure of browsing metadata like DNS queries and IP address visibility, and it works more like a privacy-focused relay system than a TLS-only fix.

- The Onion Router (Tor): Tor is designed to hide which websites you visit from network observers by routing traffic through multiple encrypted hops. It provides much stronger anonymity than ECH, but it comes with different tradeoffs, including slower performance, compatibility limitations, and a different threat model overall.

FAQ: Common questions about encrypted SNI (ESNI)

What is encrypted SNI (ESNI)?

ESNI is a method for hiding the website name that your browser normally sends during the start of an HTTPS connection. It was designed to stop the “which site is this?” part of the Transport Layer Security (TLS) handshake from being visible to networks in between.

How does Server Name Indication (SNI) affect privacy and security?

SNI doesn’t weaken the encryption on HTTPS page content, but it can expose the domain name you’re trying to reach during the connection setup. That can make it easier for networks to log which sites you visit, apply domain-based filtering, or build a rough profile of your browsing, even when the content stays encrypted.

Is encrypted SNI (ESNI) still used, or has it been replaced by ECH?

ESNI was an earlier approach and has largely been superseded by Encrypted Client Hello (ECH), which protects more than just the SNI field. In most modern discussions and deployments, ECH is the focus.

Can I enable encrypted SNI (ESNI) or Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) on my browser?

Usually, you don’t “enable ECH” directly. If your browser supports it, it’s typically automatic and only activates on sites that support it. What you can do is keep your browser updated and enable encrypted DNS (like DNS over HTTPS) to improve the chances ECH can work when available.

Which websites support encrypted SNI (ESNI) or Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) today?

There’s no simple public list you can rely on because support depends on both the site’s HTTPS front end and the site’s DNS records. In practice, ECH support is still uneven. The most reliable way to check is to test your current connection on a diagnostic page that reports whether ECH is being used.

How does encrypted SNI (ESNI) compare to traditional SNI?

Traditional Server Name Indication (SNI) sends the hostname in the clear during the Transport Layer Security (TLS) handshake. Encrypted SNI hides that hostname by encrypting it, so observers on the network path can’t read it in the same way. The tradeoff is that it requires extra support from both the browser and the website’s infrastructure, so it isn’t universal yet.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN