What is shimming in cybersecurity, and how can you protect against it?

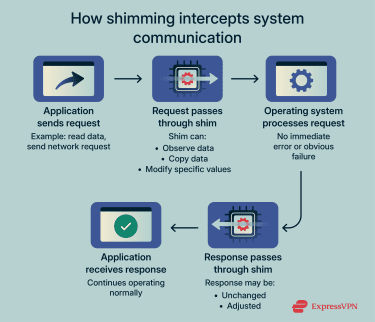

When you use a device or an app, it doesn’t handle every task by itself. To work properly, it relies on other parts of the same system to do specific jobs. A payment terminal relies on software to process card data. An app relies on the operating system to manage internet access, files, and display information.

Because much of this work happens in the background, changes inside a system aren’t always obvious from the outside. Shimming is a technique that takes advantage of this by interfering with how systems handle information behind the scenes, while everything on the outside appears to work as normal.

This guide explains what shimming actually means, how it shows up in real systems, and how to protect against the risks it can introduce.

What is shimming?

Shimming is the use of an intermediary component (called a shim) to intercept or monitor how information moves between parts of a system. The system itself continues to work normally, without it being obvious to the user that anything has changed.

How shimming attacks work

A shim can be software-based or hardware-based, depending on where the interception occurs. In software, it’s usually a small piece of code placed within the normal flow of communication between system components, so information passes through it during regular operation. In hardware, a shim can be a physical electronic component placed inside a device to intercept signals between connected parts.

A shim can be software-based or hardware-based, depending on where the interception occurs. In software, it’s usually a small piece of code placed within the normal flow of communication between system components, so information passes through it during regular operation. In hardware, a shim can be a physical electronic component placed inside a device to intercept signals between connected parts.

As data moves through the system, the shim can observe it, copy it, or adjust specific values before the data reaches its destination. Because the surrounding components still receive valid-looking inputs and outputs, they continue operating normally and don’t raise errors. From their perspective, nothing unusual has happened.

This is what makes shimming effective as an attack technique. The system keeps running, but the shim can read or influence information that trusted components rely on. That can lead to sensitive data being captured, responses being adjusted, or decisions being made based on altered inputs.

That said, shimming itself isn’t inherently malicious. Operating systems legitimately use shims for purposes like compatibility, allowing older applications to function on newer machines. It becomes a security issue when a shim is introduced without authorization. This allows a third party to observe, copy, redirect, or influence data undetected.

Types of shimming attacks

Shimming attacks are usually grouped by where the interference happens. That location determines what kind of information is exposed and how wide the impact can be.

ATM shimming

ATM shimming targets transactions at cash machines and other card readers. Attackers hide thin electronic inserts inside the card slot to capture card data as it’s read. From the outside, the machine continues to accept cards and complete transactions normally, which allows the attack to affect multiple users before it’s detected.

Because the interference is inside the reader itself, shimming is usually discovered later through signs like unusual withdrawal patterns or reports of credit card fraud, rather than through visible damage or malfunction.

Software-based shimming

Software-based shimming targets applications by interfering with the system services they rely on.

Rather than affecting the entire device, this type of shimming is usually tied to specific programs. The impact depends on what the application does and what data it handles. For example, interference around a browser, authentication process, or internal business tool can expose credentials, session data, or sensitive records tied to that software’s role.

Because it’s application-specific, malicious software-based shimming is more often associated with targeted attacks rather than mass campaigns. An attacker may focus on one program that gives them access to something valuable instead of trying to disrupt the whole system.

Driver-level shimming (kernel shimming)

Driver-level manipulation involves interfering with the software drivers an operating system uses to communicate with hardware. Drivers are trusted by the system and run with elevated permissions, which means they can see and handle data before applications do.

If a driver is abused or modified as part of a shimming attack, it can monitor or influence things like network traffic, input, or storage activity without applications being aware. These techniques are commonly described as “driver manipulation” or “driver hooking.” They’re often used by rootkits (malware designed to hide deep inside a system) because they allow extensive access while remaining difficult to detect.

Mobile app shimming

Mobile platforms work differently from desktop operating systems. They place tighter limits on how apps interact with the system and with each other, which makes it harder to insert extra layers into core processes in the same way.

Still, shimming can happen on mobile platforms when many apps rely on the same shared frameworks or libraries. It’s common for apps to depend on shared components for tasks like authentication, analytics, payments, or network communication. If one of these shared components is compromised as part of a shimming technique, it can affect how data is handled across every app that relies on it.

This kind of interference is rare on platforms that strictly control which apps can be installed and what they’re allowed to access. On devices where apps can be installed from unknown sources or system protections are loosened, there are more opportunities for shared components to be affected.

How to detect a shimming attack

Warning signs and red flags for individuals

In everyday life, shimming-related risks are most visible in payment and physical device scenarios. Software-based shimming is much less likely to affect consumers directly, unless they’re using devices with modified system software or installing apps from untrusted sources.

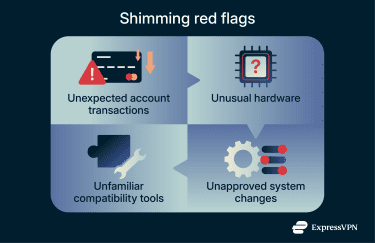

Some of the warning signs include:

- Unusual account activity or transaction alerts: This includes charges you don’t recognize, small “test” payments, or unexplained withdrawals. Real-time alerts for purchases you’re not making are also a sign to review recent card activity and act quickly.

- Card readers that look or behave unusually: A loose or bulky card slot, difficulty inserting a card, visible tampering, or a keypad that feels different from nearby terminals. In these cases, avoid using the device and switch to another payment method or location.

How organizations can monitor for threats

For organizations, shimming usually isn’t caught by a single alert. Instead, it often comes to light during routine work such as troubleshooting, audits, or security reviews. These reviews may uncover changes that don’t match how the system is expected to be built or maintained.

Unexplained system or configuration changes

Systems normally change because of patches, upgrades, or planned configuration updates. Look for settings, drivers, or supporting components that change even though no update was scheduled or approved. These can be an early sign that something is influencing system behavior behind the scenes.

Unexpected use of compatibility features

On Windows systems, compatibility features are designed to solve specific problems, such as keeping older software running. Some of these features are implemented using shims, and they’re usually enabled deliberately for a documented reason.

If compatibility components appear without a support ticket, documented requirement, or known software issue, it may indicate a shim influencing application behavior.

Apps behaving differently without a version change

Track whether applications begin behaving differently in how they handle requests or data, even though their version number, update history, and deployment records haven’t changed. When behavior changes without a software update, it’s a signal to examine what sits underneath the application and how requests are being handled.

How to prevent and protect against shimming

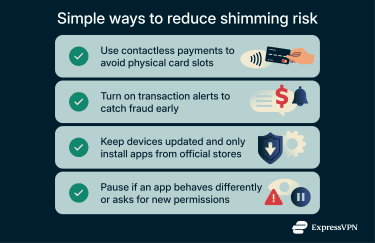

As an individual, you can reduce risk by limiting exposure and responding quickly to warning signs. Organizations prevent shimming by controlling what runs in their environments and planning for containment if controls fail.

Practical steps for individuals

- Use lower-risk payment methods when available: Contactless payments and digital wallets like Apple Pay and PayPal reduce reliance on physical card slots. This doesn’t eliminate fraud risks, but it removes one common point of attack.

- Enable transaction alerts on financial accounts: Real-time alerts won’t prevent shimming, but they can shorten the time between a compromise and a response. Faster detection makes it easier to stop fraud before losses grow.

- Keep devices updated and apps sourced correctly: Software-based shimming typically requires some level of access to the system. Installing updates and sticking to official app stores reduces the chances that unauthorized components can be introduced.

- Pause when behavior doesn’t match expectations: If an app suddenly asks for new permissions or fails in unusual ways, slow down. Confirm that it was installed from an official app store or the developer’s website. Also, check the app’s store listing to make sure the publisher matches what you expect before continuing, especially when sensitive data is involved.

Protective measures for organizations

- Limit what can run and load on systems: Restrict which programs, extensions, and system components are permitted to start on your systems. When only approved software can run, it becomes significantly harder for unauthorized code to infiltrate normal system operations.

- Keep systems up to date: Regular patching reduces the number of vulnerabilities attackers can exploit.

- Protect high-risk hardware environments: Devices like ATMs, kiosks, and card readers need both technical and physical checks. Regular inspections, clear service records, and simple tamper-evident seals make it easier to spot changes that shouldn’t be there.

- Plan for impact, not just detection: Don’t stop at spotting a problem. Have a clear plan for what happens next, including how to handle service disruption, data exposure, investigation, and recovery. This should also account for cases where attackers later attempt cyber extortion. Preparing for these scenarios in advance helps reduce downtime, limit losses, and lower the true cost of cyberattacks.

Shimming vs. other cybersecurity threats

The threats below are sometimes confused with shimming, but they describe very different changes to how software behaves.

Shimming vs. spoofing

Spoofing is the act of impersonating a trusted source to mislead a user or a system. It’s commonly used to enable further actions such as obtaining sensitive information, redirecting traffic, spreading malware, or gaining unauthorized access.

For example, a spoofed website may look identical to a legitimate login page, so a user enters their username and password. A spoofed email sender may appear to come from a known contact, so the recipient clicks a link or opens an attachment.

Shimming doesn’t rely on imitation or tricking users into believing something is real. The real application, service, or device is still involved. The influence happens inside the system’s own communication paths, not by convincing someone to trust fake information.

Shimming vs. DLL injection

Dynamic-link library (DLL) injection is a technique where an attacker makes a legitimate program load extra code it wasn’t meant to run. That added code then runs inside the program, with the same access and permissions as the program itself.

This can let an attacker read data the program handles, manipulate its behavior, or control how it interacts with the system. For example, injecting code into a browser could allow access to session data or credentials handled by that browser.

Not all DLL injection is shimming. However, it can be a method of shimming if the goal of the inserted code is to intercept, observe, or modify a program’s functions without replacing the program itself.

Shimming vs. code injection

Code injection happens when an application fails to keep user input separate from the instructions it uses to operate.

Applications often accept input through things like form fields, search boxes, or web addresses. That input is supposed to be treated as data, like text to display or values to store. When an application doesn’t handle input safely, parts of it may instead be interpreted as commands.

If that happens, attackers can cause the system to carry out actions it was never designed to allow. This can include revealing restricted data, changing stored information, or running code automatically when a page loads.

Shimming works differently. It doesn’t depend on tricking the application with specially crafted input. The application can receive normal, expected input and still behave incorrectly because the way data is handled around it has been altered.

Shimming vs. process hollowing

Process hollowing is a takeover technique. A legitimate program is started, so it appears trusted by the system. Once running, its original code is removed from memory and replaced with malicious code.

From the system’s perspective, the process name, path, and identity look normal. Internally, the program is no longer doing what it was designed to do. It has effectively been replaced while keeping its outward appearance.

Shimming doesn’t remove or replace a program’s code. The original program continues to run as intended. The influence happens alongside it rather than by turning the program into something else.

Shimming vs. image hijacking

Image hijacking works by interfering with how a system chooses which program to run. When a command or application is launched, the operating system looks in certain locations to find the executable file. If a malicious executable is placed in a location that gets checked first, the system may run that file instead of the one it was meant to use.

In that case, the wrong program runs even though everything looks normal on the surface. The system believes it launched the intended application, but it’s actually executing something else, which can lead to data exposure or unwanted actions.

Shimming doesn’t cause a different program to run. The correct application still launches and operates as expected. The change happens in how specific actions or requests are handled while it runs.

FAQ: Common questions about shimming in cybersecurity

Can antivirus software detect shimming?

Sometimes, but only in specific cases. Antivirus software may detect shimming when it involves known malicious files, unauthorized driver changes, or obvious system tampering. However, many shimming techniques rely on legitimate system components and don’t introduce a clearly malicious file. That means standard antivirus scans often don’t catch them.

Is shimming still a threat today?

Yes, but it’s less common than more visible attacks. Shimming is still used in targeted attacks and payment fraud because it can access data without causing obvious problems like crashes or alerts. Stronger platform protections have reduced the risk, but the technique hasn’t disappeared.

How is shimming different from skimming?

Skimming captures data at the point of entry, such as when a card is swiped or details are typed into a form. Shimming operates inside the system, intercepting data as it moves between internal components after the input has already been accepted. In card fraud, skimmers sit on the outside of readers, while shims are placed deeper inside the device’s internal data path.

What industries are most at risk?

Industries that rely on trusted system interactions or shared infrastructure face higher risks of shimming attacks. This includes financial services, retail payments, healthcare, and enterprise IT environments. Any setup with terminals, legacy systems, or shared components can be a target.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN