Understanding domain fronting: A comprehensive guide

When you surf the internet, you trust that your web traffic is going where you think it is. Domain fronting challenges this assumption by masking the true destination of your traffic.

This technique can improve digital privacy, but it can also be misused. In this article, we’ll break down how domain fronting works, why it’s used, and the risks it introduces for network security.

What is domain fronting?

Domain fronting is a networking technique that hides the true destination of a connection to outside observers, such as internet providers and firewalls, by making it appear as though it’s being made to a different domain.

Technical mechanisms

Domain fronting exploits two foundational internet technologies: the shared infrastructure of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) and the way HTTPS connections communicate domain information.

CDNs are distributed networks of edge servers that cache and deliver content from locations closer to users. They host thousands of different websites on shared infrastructure using the same IP addresses. This creates a problem: when you connect to a shared IP address, how does the server know which of the thousands of websites you want?

HTTPS solves this by communicating which website you want in two places: once in plaintext before encryption starts, which can be seen by anyone monitoring the network, and once after encryption is active, which includes the request for the exact website and can only be seen by the CDN server itself.

Normally, both contain the same domain name. Domain fronting leverages this setup by putting different domains in these two places. The first, plaintext field contains the decoy domain, while the encrypted field contains the actual target domain.

Why it matters in network security

When misused, domain fronting allows attackers to hide blocked traffic behind legitimate CDN connections. This makes it difficult to block that traffic at the domain level without also disrupting unrelated websites and services hosted on the same infrastructure.

In practice, this creates a few specific problems for defenders because:

- Malicious traffic appears legitimate: Attackers can move malware or exfiltrate data, while logs and cybersecurity monitoring tools only show connections to a well-known CDN or cloud hostname.

- Investigation and response become difficult: During incident response, defenders may not be able to tell where the traffic actually went from standard network records alone, because the visible destination is the “front” hostname.

- Traditional defenses lose precision: Controls that rely on destination domains and reputation, such as blocklists, allowlists, and hostname-based filtering, may be bypassed when the visible hostname matches a legitimate, widely used service.

How domain fronting works

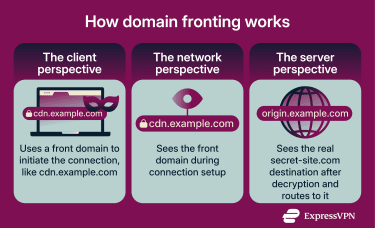

Understanding how domain fronting works requires examining the client, front domain, and hidden destination, as well as the step-by-step request flow that makes this technique possible.

The structure of domain fronting

A successful domain fronting setup involves three main parties:

- The client: The device or software initiating the connection.

- The front domain: The hostname shown during HTTPS setup and perceived as “safe” by any network that can only see early connection metadata.

- The hidden destination: The hostname the client actually wants to reach, carried inside the encrypted web request.

For domain fronting to work, the front domain and the hidden destination must both be hosted behind the same CDN. That shared intermediary makes it possible for the connection to start as a “front domain” and then be routed to the hidden destination after the encrypted request is visible to the edge.

TLS handshake and SNI

When a user visits a website hosted by a CDN, their browser or app connects to the CDN's IP address and starts a Transport Layer Security (TLS) handshake.

The TLS handshake is the short “setup conversation” that happens before any HTTPS data is exchanged. During this step, the client shares the domain it wants to reach in the Server Name Indication (SNI) field. The SNI tells the CDN server which of the thousands of websites sharing that IP address the client is trying to reach, so the server knows which TLS certificate to present. The certificate proves the server's identity and enables the browser to establish the encrypted connection.

Since this happens before encryption, the SNI is sent in plaintext, meaning anyone watching the network can see which domain is in the SNI field. That visibility is what domain fronting relies on. In setups that use domain fronting, the decoy domain is placed in the SNI field instead of the real destination. Network monitors see this approved domain and allow the connection through.

Host header explanation

Once the encrypted connection is established, the browser sends an HTTP request, which is the message that asks the server for a specific webpage or resource. This request travels through the encrypted tunnel and includes the Host header, which specifies which website the request is for.

The Host header serves a different purpose than SNI. While SNI tells the server which certificate to present during the initial handshake, the Host header tells the receiving web server which site configuration or backend service the request is intended for once encryption is already active.

In domain fronting, the Host header contains the intended destination. Because this header is sent inside the encrypted connection, it is not visible to observers who can only see connection metadata. The CDN server can read it because it terminates the TLS connection and decrypts the request.

Domain fronting today and the rise of ECH

Most major CDNs now require the SNI and the Host header to match, which prevents traditional domain fronting from working on their platforms. Nowadays, hostname concealment in TLS connections is primarily achieved through Encrypted Client Hello (ECH).

ECH is a TLS extension that encrypts part of the initial TLS handshake message, called ClientHello, that includes the SNI.

To do this, it creates two versions:

- An outer ClientHello: Contains a public-facing name and enough information to route the connection to the correct server infrastructure.

- An inner ClientHello: Contains the actual SNI and full handshake details.

The client encrypts the inner ClientHello using a public key published by the server (typically via the Domain Name System (DNS)) and attaches it to the outer ClientHello as an encrypted extension. When the server receives the connection, it uses its private key to decrypt the inner message and recover the real hostname before continuing the handshake normally.

Because the server ultimately presents a certificate for the actual destination hostname contained in the decrypted inner ClientHello, there’s no mismatch between the requested domain and the certificate identity, like in traditional domain fronting.

At the same time, the true hostname remains encrypted within the handshake. Network observers can see that a TLS connection is being established and can see the outer name, but it’s much more difficult to determine the actual destination hostname contained in the encrypted inner ClientHello.

Use cases of domain fronting

Domain fronting has been used in various contexts: some to improve privacy and access, others to test or evade security controls. Here are the most notable use cases:

- Secure communication: Users in sensitive roles have used domain fronting to access encrypted messaging services without revealing their true destination.

- Protection from network surveillance: Because domain fronting hides the real destination inside an encrypted connection, it makes it harder for network observers to detect what a user is accessing.

- Red team operations: Security professionals use domain fronting in authorized simulations to test how well organizations detect stealthy command-and-control traffic.

- Virtual private network (VPN) obfuscation: Some VPN services use domain fronting to obscure the fact that a VPN is in use. In networks where VPNs are blocked or flagged, domain fronting can make VPN traffic appear to originate from a regular site.

Security implications of domain fronting

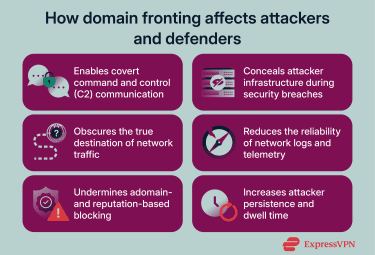

Domain fronting can create blind spots in modern security stacks because it undermines several assumptions commonly used in network security monitoring, enforcement, and investigation.

Risks and threat vectors

Any technique that weakens the link between what a defender observes and what is actually happening on the network introduces new risk. In the case of misusing domain fronting, that risk primarily comes from how attackers can leverage it to circumvent certain domain-based controls that rely on domain identity and traffic reputation.

One example of how domain fronting can be misused is the support of command and control (C2) operations. In a malicious context, C2 infrastructure could be used to issue instructions to compromised systems, exfiltrate stolen data, deploy additional payloads, or maintain unauthorized access to a target network.

In incident response, domain fronting behavior can distort what defenders see in network telemetry. DNS logs, TLS handshake logs, and allowlist-based controls may only show the front domain and the CDN IP, which can make the connection appear routine at the domain level.

Defensive challenges

The nature of domain fronting creates two key challenges when trying to defend against it. Firstly, there is reduced visibility in logs. Front domains typically don’t reveal the intended hostname and because the traffic is encrypted, it’s more difficult to see the indicators.

The second challenge is that it’s harder to block traffic based on domains because the domain appears to go to an allowlisted site. Additionally, blocking the front domain could disrupt other use of the domain.

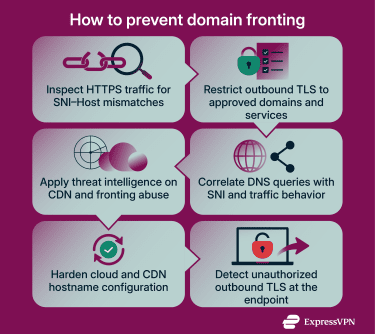

Best practices: Mitigating the effects of domain fronting

Organizations that rely heavily on domain-based controls can reduce exposure by combining multiple layers of visibility and enforcement.

TLS inspection and hostname verification

Consider deploying a gateway or transparent proxy that intercepts HTTPS traffic and compares the SNI field to the HTTP Host header inside the encrypted request. This requires the proxy to decrypt the TLS connection, inspect the contents, and re-encrypt it before forwarding.

The challenge here is that TLS inspection requires your organization to act as an authorized intermediary for all HTTPS traffic, which introduces complexity around certificate management and user privacy.

Use strict domain allowlists (zero trust)

Instead of trying to block all malicious domains, consider creating an allowlist for outbound TLS connections to known and necessary domains. This zero-trust approach limits an attacker's options for domain fronting.

This strategy is most practical in enterprise environments where cloud and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) dependencies are well-defined. Maintaining an accurate inventory of required services is essential, and allowlists should be reviewed regularly as business needs evolve.

Monitor DNS and SNI logs

Domain fronting sometimes creates detectable patterns. For example, you might see DNS lookups for front domains (like major CDN providers), but the actual traffic patterns may not match typical usage of those services.

Look for anomalies like brief DNS spikes followed by no corresponding traffic, or high volumes of DNS queries to CDN providers that your organization doesn't normally use heavily.

Automated analysis tools can baseline normal DNS and SNI patterns for your network and alert on deviations. While this won't catch every case, it can provide valuable signals when combined with other detection methods.

Leverage threat intelligence

Security vendors and research organizations publish indicators of compromise (IOCs) related to malicious infrastructure, including domains and network patterns that may use concealment techniques such as domain fronting. Integrating relevant threat intelligence feeds into monitoring systems can provide additional context beyond hostname visibility alone and help identify known malicious activity.

Because domain-based controls have limitations, threat intelligence can serve as a complementary signal rather than a standalone solution.

Harden your cloud and CDN configuration

Most major cloud and CDN providers no longer support traditional domain fronting by default. However, misconfigurations can still create opportunities for abuse. To reduce risk:

- Avoid wildcard hostnames (such as *.example.com) unless there’s a clear operational need.

- Use explicit, enumerated hostnames instead of catch-all routing rules.

- Ensure certificates only cover domains you explicitly control.

- Regularly audit CDN and reverse proxy routing rules.

Endpoint monitoring

Endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools that monitor TLS connection behavior directly on devices are worth considering because some domain fronting techniques rely on methods that generate abnormal process activity or network patterns.

EDR solutions can help correlate application behavior, outbound network calls, and process execution patterns to identify suspicious activity even when network-level inspection is limited by encryption or ECH. Endpoint monitoring is especially valuable for remote workers or devices outside your corporate network perimeter.

FAQ: Common questions about domain fronting

Is domain fronting illegal?

Domain fronting isn’t explicitly prohibited in many jurisdictions, but many cloud providers ban it. Services such as Google Cloud and AWS have blocked it on their infrastructure, and using it may violate their terms of service.

What is the impact of domain fronting on security?

Domain fronting makes it hard to see where traffic is going. That gives attackers an avenue to hide malware and avoid detection, especially when they blend into traffic from trusted cloud services. It weakens visibility for defenders and makes it harder to apply domain-based security rules.

How do major companies handle domain fronting?

Most major cloud providers now block domain fronting. They’ve adjusted their routing systems to reject traffic with mismatched domain names between the TLS handshake and HTTP request. This stops abuse but also limits the technique’s availability for legitimate uses.

What defenses are effective against domain fronting attacks?

Traditional defenses can miss domain fronting because the true destination is hidden. Some security tools compare the SNI and Host headers for mismatches, but this usually requires decryption. Blocking risky CDNs or analyzing traffic patterns can help, though these methods also risk breaking legitimate services.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN