Apps for opioid addiction treatment and recovery

Data sharing and privacy risks

Our team at the ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab studied ten smartphone apps utilized for opioid addiction treatment and recovery, focusing on privacy and security issues.

Introduction

Opioid addiction and overdoses have had a devastating impact on communities in the United States during the 21st century. According to the CDC, nearly 500,000 people died from overdoses involving any opioid, prescription or illicit, between 1999 and 2019. In 2019 alone, preliminary overdose numbers suggest 90,000 people died from drug overdoses, a 29% increase from 2018. The opioid epidemic continues to disproportionately impact people of color and rural communities where access to evidence-based treatments remain limited.

The Covid-19 pandemic has arisen against the backdrop of the opioid crisis, completely altering the landscape of addiction treatment and recovery. Due to an interest in limiting Covid-19 transmission, healthcare and mental health apps became prominent over the past year. In February 2020, the CDC advised the usage of apps as part of their social distancing guidance, recommending that health care facilities and providers offer clinical services through virtual means such as telehealth. One report found that this resulted in a 154% increase in telehealth visits during the last week of March 2020 alone.

The rise of telehealth treatment

Addiction is a brain disease that affects approximately 23 million Americans, but only one in ten receive the treatment they need. However, addiction treatment is a $35 billion industry in the U.S. Websites and smartphone apps that deliver addiction treatment and support recovery are climbing in popularity. Both investor and government interest has turned to telehealth as a tool to combat the surging opioid crisis. All the while, traditional brick-and-mortar addiction treatment facilities have faced unprecedented budget crises and closures related to Covid-19.

App-based approaches to public health problems have faced increasing scrutiny for lack of appropriate privacy and security. The Covid-19 contact tracing framework developed by Google was found to have substantial privacy issues, with Bluetooth identifiers stored in Android system logs. This follows a suspension of Norway’s contact tracing app, ranked alongside Kuwait and Bahrain for its location data leakage. These country-wide approaches joined Switzerland’s “SwissCovid” in notoriety, a contact tracing app that was found to have numerous privacy flaws and linked to X-Mode, a location tracker we studied at Digital Security Lab in our Investigation Xoth.

Due to these issues with other health apps, our team wanted to understand if the kinds of privacy and security issues that plague these approaches to the Covid-19 pandemic could also affect telehealth solutions for addiction treatment and recovery. These services have been developed in an environment of unclear U.S. federal guidance in regard to the handling and disclosure of patient information, as well as a patchwork of laws at the state level. New legislation has been proposed in the U.S. to establish and expand telehealth access after the public health emergency posed by Covid-19 ends. However, little has been done to improve privacy protections for people using these approaches.

To better understand these issues, our team at the ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab studied ten smartphone apps utilized for opioid addiction treatment and recovery, focusing on privacy and security issues:

These apps have a vast reach with approximately 180,000 downloads from Google Play, coverage in all 50 states, and more than $300 million in funding from investment groups and the federal government. All of these apps have corresponding iOS versions. However, as with our January 2021 investigation into smartphone apps, we limited analysis to the Android operating system. This scope is aligned with recent cross-sectional studies of telehealth apps, which also focus on Android and Google Play. We note that Android is the world’s most popular mobile operating system and the leader in the U.S., with more than 130 million users. Historically, privacy issues that persist in Android versions of apps also affect iOS users, though updates to iOS settings are altering the reach of user tracking on the platform.

In addition, app marketplace downloads do not fully capture the reach or scope of these apps, which sometimes represent growing and influential social networks. Loosid alone claims over 100,000 users and 1.4 million “dating interactions,” and it claims to be “the world’s most popular sobriety and recovery app.” Sober Grid is branded “the world's most popular mobile sober community” and, though the total number of users is not known, its significance was noted in a 2020 study.

Addiction impacts millions worldwide, and the audience of the apps in this report is not limited to the U.S. Some of these services are not restricted to the U.S. and healthcare and addiction treatment are regulated differently in each country.

Collaboration on this report

For this report, we partnered with the Opioid Policy Institute (OPI) and the Defensive Lab Agency (DLA). Additionally, we engaged researchers from Yale University and lawyers from the Legal Action Center (LAC) for their feedback and input. All of the contributors agree that the findings include troubling and conspicuous signs of privacy and, potentially, security issues.

That said, we wish to emphasize the central role that addiction recovery apps may play in the lives of individuals with substance use disorders. It is paramount that criticism of telehealth apps not be misconstrued as calls for their removal from distribution or bans on their usage. Instead, we wish to place emphasis on the importance of patient and end-user privacy, shining a light on growing and prescient concerns within the domain of telehealth treatment.

This report serves the ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab’s mission by advancing public understanding of the digital landscape. Often, the developers of these apps receive public funding via U.S. Department of Health & Human Services agencies such as the National Institutes of Health or other agencies such as the National Science Foundation.

Analysis

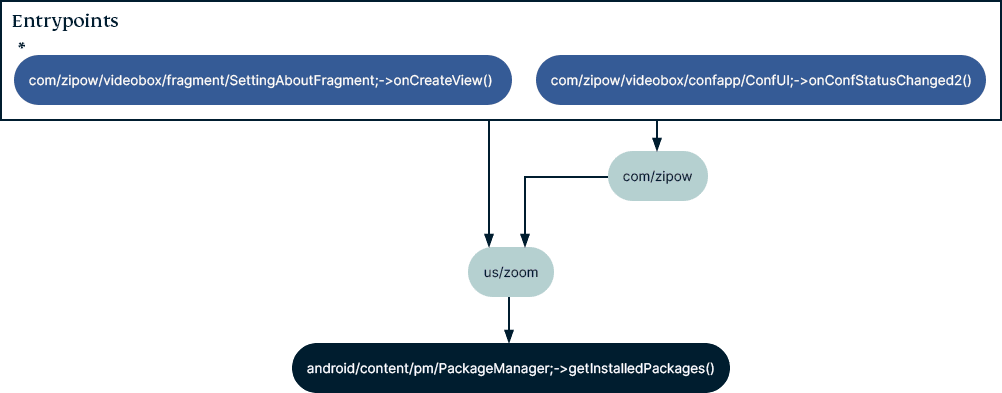

We focus on data access and permissions, visualizing app activity via source code analysis. This report relies upon insights gleaned from static analysis, using a process similar to the one we outlined in Investigation Xoth. Building upon the techniques we used previously to analyze app source code, we generate “call graphs” that illustrate how information flows through each app. The software that was developed to generate these call graphs, as well as source code snippets corresponding to these visualizations, has now been released by Defensive Lab Agency under a free and open-source license.

Call graphs represent relationships between subroutines in a computer program and give a view into the data that components of an app can access and modify. In this example, software developed by Zoom that is present in a telehealth app accesses the list of installed packages on a smartphone:

Such information could, for example, be used to build a fingerprint on a specific smartphone and its owner, statistically inferring their identity.

Though, in many cases, we can correlate this information with network endpoints connected to a specific app, we don’t assume that vendors like Zoom are doing something nefarious with this information. However, such evidence is a strong indicator of data sharing between an app and a third party. In the context of addiction treatment and recovery, there are strong regulatory controls over such sharing in the U.S. when it occurs in a traditional brick-and-mortar healthcare setting. In the emerging frontier of telehealth, however, there is still much ambiguity.

Identifying users as individuals

Smartphone users are the subject of intense surveillance by private and public actors. For advertisers and data brokers, a key function of smartphones is the capability to identify the individual carrying the device. Since smartphones are moving targets, so to speak, the location and history of movement for a person can also be deduced. Correlated with data from other smartphones and IoT hardware such as beacon devices, smart speakers, and even the sidewalks in smart cities, data profiles can be compiled on an individual person.

This impact of identifiers on consumer privacy has been acknowledged by both Google and Apple in recent policy changes. In May 2021, Apple implemented changes to iOS, with policies aimed at limiting the usage of the Identifier For Advertisers (IDFA) and prompting users to consent when it is collected. Google followed by announcing a change to its developer policy and will begin limiting access to the Android advertising ID (AAID) and has promised to roll out an alternative and less intrusive identifier, starting in July 2021.

Perhaps the most alarming revelation from our study of ten opioid addiction treatment and recovery apps is the consistent access of unique identifiers, given the sensitivity of privacy around health and substance use issues. These range from software-defined IDs to those that are tied strongly to the smartphone’s hardware and the consumer’s account with a cell provider.

-

7 out of 10 apps access the advertising ID (Bicycle Health, Boulder Care, Confidant Health, DynamiCare Health, Kaden Health, Sober Grid, Workit Health).

-

5 apps access the phone number (Bicycle Health, Loosid, Kaden Health, Pear Reset-O, Workit Health).

-

8 apps access other telephony information such as the carrier name (Bicycle Health, Boulder Care, Confidant Health, Kaden Health, Loosid, Pear Reset-O, Sober Grid, Workit Health).

-

3 apps access the IMEI and IMSI from the cell provider (Confidant Health, Kaden Health, Sober Grid).

-

1 app accesses the serial number from the cell SIM card (Kaden Health).

-

3 apps access the network information/IP address (Confidant Health, Kaden Health, Loosid).

-

1 app access the hardware address/MAC address (Sober Grid).

This information is certainly sensitive in the case of addiction treatment and recovery. It is not clear why this information is made available to third parties, as our analysis of the apps reveals.

Additionally, sensitive information which may improve the capability to surveil individuals is also accessed by many of these apps. These include logs of device activity and the list of other apps installed on the device, as well as location data.

-

2 apps access the list of installed apps (Bicycle Health, Kaden Health).

-

1 app can read the device logs (Sober Grid).

Smartphone data types made available to developers and third-parties in 10 opioid addiction treatment and recovery apps

| Bicycle Health | Boulder Care | Confidant Health | DynamiCare Health | Kaden Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of installed apps | Zoom | Stripe | |||

| Device logs | |||||

| Location | Amplitude | Facebook, OneSignal | DynamiCare Health | Facebook, Stripe | |

| Advertising ID | OneSignal | ||||

| IP address | Branch | Stripe | |||

| MAC address | |||||

| IMEI and/or IMSI | Segment | Stripe | |||

| SIM serial | Stripe | ||||

| Phone number | Learnium, Zoom | Learnium, Stripe | |||

| Carrier name | Branch, Learnium, Zoom | Amplitude | Branch, OneSignal, Segment | Learnium, Stripe |

| Loosid | Pear Reset-O | PursueCare | Sober Grid | Workit Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of installed apps | |||||

| Device logs | Localytics | ||||

| Location | AppsFlyer, OneSignal | Facebook, Google, Localytics, OneSignal, Sober Grid | AppsFlyer, Facebook | ||

| Advertising ID | Google, Localytics, OneSignal | AppsFlyer, Google | |||

| IP Address | AppsFlyer, Mixpanel | ||||

| MAC Address | Sober Grid | ||||

| IMEI and/or IMSI | Localytics, Sober Grid | ||||

| SIM serial | |||||

| Phone number | Learnium | Learnium | Learnium | ||

| Carrier name | AppsFlyer, Facebook, Learnium, Microsoft, Mixpanel | Learnium, Microsoft | Google, Localytics, OneSignal | AppsFlyer, Facebook, Learnium |

Sensor overload

Smartphone sensors are a battleground for personal privacy, offering a vast array of information for exploitation by malicious hackers and data brokers alike. Conversations about smartphone privacy include a steadily increasing array of sensors such as accelerometers, ambient light sensors, and LiDAR. Where privacy and security are concerned, however, five attack vectors stand out: GPS, Bluetooth, cell radio, camera, and microphone.

GPS, Bluetooth, and cell radio are commonly used for location tracking and Bluetooth, in particular, is on the rise as a channel for exfiltration of private user data. As products such as Apple’s AirTags are introduced, the physical world around our smartphones is becoming filled with Bluetooth sensors, including “beacons” which can determine movement and proximity of users to a finer degree than more coarse location methods such as cell radio triangulation.

Many of the apps we studied gather location information in some form, relying upon a mix of GPS, mobile network/cell radio, and Bluetooth technology. This location information, especially when correlated with unique identifiers, strengthens the capability for tracking an individual person who is carrying the smartphone, their daily habits and behaviors, and even pinpointing their friends and family.

-

7 out of 10 apps request permission to make Bluetooth connections (Bicycle Health, Boulder Care, Confidant Health, DynamiCare Health, Kaden Health, Loosid, PursueCare).

-

7 out of 10 apps access location data, if available (Boulder Care, Confidant Health, DynamiCare Health, Kaden Health, Loosid, Sober Grid, Workit Health). Three apps request permission to determine coarse and fine location based upon GPS and/or mobile network information (DynamiCare Health, Loosid, Sober Grid).

Data permissions requested by 10 opioid addiction treatment and recovery apps

| Bicycle Health | Boulder Care | Confidant Health | DynamiCare Health | Kaden Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read device logs | |||||

| Create Bluetooth connections | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Access coarse and fine location | Yes | ||||

| Determine phone call info | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Make phone calls | Yes | ||||

| Read and/or write contacts | |||||

| Read and/or write calendar | Yes | ||||

| Record audio and/or video | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Loosid | Pear Reset-O | PursueCare | Sober Grid | Workit Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read device logs | Yes | ||||

| Create Bluetooth connections | Yes | Yes | |||

| Access coarse and fine location | Yes | Yes | |||

| Determine phone call info | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Make phone calls | Yes | ||||

| Read and/or write contacts | Yes | Yes | |||

| Read and/or write calendar | Yes | ||||

| Record audio and/or video | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

-

6 out of 10 apps request permission to determine calling information including whether a call is active, the number that call is connected to (Bicycle Health, Boulder Care, Confidant Health, Loosid, PursueCare, Sober Grid).

-

2 apps request permission to initiate phone calls (Bicycle Health, Sober Grid).

-

2 apps request permission to read and/or modify contacts in the address book (Loosid, Sober Grid).

-

3 apps request permission to read and/or modify calendar items (Confidant Health, Kaden Health, Loosid).

Though we have not observed unwanted or unauthorized access via this functionality, consumers would do well to limit permissions in these apps that relate to camera and microphone, calls, calendar, and address book unless they are actively using features that require them.

Third-party sharing

The modern-day app economy relies upon extraction of detailed user information to boost revenue and perceived value. Developers who utilize tracker Software Development Kits (SDKs) often have a stake in data collection from smartphone users. SDKs execute code and communicate over the internet in ways that may compromise user information.

In Investigation Xoth, ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab revealed the relationships between a cluster of tracker SDKs that relied specifically upon location data. In our current study, we have also discovered a high prevalence of tracker SDKs, though their approaches to data collection and processing vary.

In some cases, SDKs are designed specifically to collect and aggregate data about the behavior, location, or identities of smartphone users. In other cases, such surveillance is a valuable byproduct of the SDK’s core functionality — an app that provides navigation to a recovery center, for example, may also be tracking a user’s movements throughout the day and sending that data back to the app’s developers and third parties.

App developers have decided to include tracker SDKs in apps for a variety of reasons, and we do not categorize all usage of trackers as malicious or condemn the app authors. Additionally, given the complexity and pace of software development, some developers may not be aware that trackers are in their app or may not know the full implications of bundling such code before publishing.

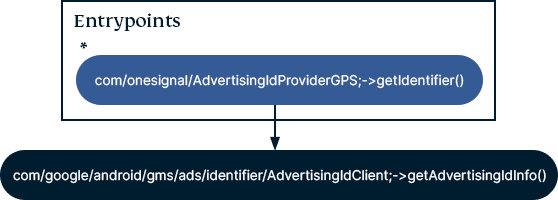

The existence of tracker SDKs can reveal potential data-sharing activity. For example, this call graph generated by studying the Confidant Health app reveals that OneSignal SDK has access to the Android Advertising ID (AAID):

Whether or not OneSignal builds data profiles on Confidant Health users cannot be proven with this information alone. However, this is a strong indicator that OneSignal collects and processes the AAID.Though the details of data-sharing relationships between tracker SDKs and the apps we studied are not known, their presence in seven out of ten apps is a cause for concern in relation to user and patient privacy. These include:

We also list reports from the crowdsourced database Exodus Privacy in the Github repository for this study, which note the presence of additional SDKs that were not revealed via our analysis. Of the ten apps, Exodus Privacy reports that only PursueCare contains zero tracker SDKs.

SDK trackers in 10 opioid addition treatment and recovery apps

| Bicycle Health | Boulder Care | Confidant Health | DynamiCare Health | Kaden Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | Yes | ||||

| AppsFlyer | |||||

| Branch | Yes | Yes | |||

| Facebook Analytics | Yes | Yes | |||

| Google AdMob | Yes | Yes | |||

| Localytics | |||||

| Mixpanel | |||||

| OneSignal | Yes | ||||

| Segment | Yes | ||||

| Other SDKs listed by Exodus Privacy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Loosid | Pear Reset-O | Pursue Care | Sober Grid | Workit Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | |||||

| AppsFlyer | Yes | Yes | |||

| Branch | |||||

| Facebook Analytics | Yes | ||||

| Google AdMob | Yes | ||||

| Localytics | Yes | ||||

| Mixpanel | Yes | ||||

| OneSignal | Yes | Yes | |||

| Segment | |||||

| Other SDKs listed by Exodus Privacy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Conclusion

Our findings indicate data-sharing trends in opioid addiction treatment and recovery apps. Though each app may differ in its implementation, the sheer amount of data available to the majority of the apps we studied raises questions about the privacy and security practices of telehealth apps. People who use these services have a reasonable expectation of privacy based on the notions of disclosure in regard to healthcare data. We have determined that a high degree of trust is required by these apps, including the use of camera and microphone, call data, location information, Bluetooth connections, and even access to a smartphone’s list of installed apps, contacts, and calendar.

Most troubling, however, is the access of unique identifiers by the majority of these telehealth apps and the capability for sharing these identifiers with third parties. This is not limited to the AAID and includes sensitive information tied to the smartphone network, hardware, and firmware. Professionals and healthcare providers in the U.S. are bound by laws, regulations, and ethical duties in this regard, including 42 CFR Part 2 and HIPAA which outline strong controls over consent and disclosure of patient information related to treatment for addiction.

That said, we wish to emphasize the central role that addiction treatment and recovery apps may play in the lives of people with an opioid addiction. We do not wish to see any of the apps we've identified in this report to be reflexively removed or banned from app stores such as Google Play, and instead recommend that privacy and security concerns be addressed by the developers and updated versions of apps be distributed to users. Patients should be aware that these services may violate expectations of privacy that someone would have with traditional addiction treatment and may not comply with the privacy and security protections for in-person treatment.

Providers should be aware that these services may not be handling patient privacy as a priority and creating risks for patients. Funders should be aware that these issues are a core component of the service and need thorough vetting before funding. Regulators should be aware that the vacuum of guidance for addiction treatment apps has been filled by a variety of telehealth services. These services may not protect patient privacy in accordance with 42 CFR Part 2 and HIPAA and are in need of additional guidance to protect patients and providers who use these services.

Through our work, we wish to place emphasis on the importance of patient and end-user privacy, shining a light on growing and prescient concerns within the domain of telehealth opioid addiction treatment and recovery. For more details on these apps including call graphs and more detailed tracker information, visit our repository of detailed findings.

For patients of these services

For patients of these services: If you or a family member used one of these services and find the disclosure of this data to be problematic, please contact the Office of Civil Rights through Health and Human Services to file a formal complaint or contact the Legal Action Center.

Recovery from addiction is possible

If you are in the U.S. and in need of help, please call the free and confidential treatment referral hotline (1-800-662-HELP) or visit findtreatment.gov

Covering this report?

If you are sharing the information in this report with your readers or viewers, please consult the guidance at reportingonaddiction.org