What is OAuth 2.0, and how does it work

Modern apps rarely operate in isolation. Email clients connect to calendars, productivity tools link to cloud storage, and apps request access to existing accounts instead of creating new logins. These connections save time, but they also raise a critical question: what access is being granted, and who controls it?

When authorization is handled poorly, apps can keep access longer than intended, or access tokens can be leaked or misused, sometimes without a password ever being stolen.

Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0 is the industry-standard framework for delegated authorization, and understanding its roles and flows helps explain how these handoffs work and why common implementation mistakes keep repeating.

What is OAuth 2.0?

OAuth 2.0 is a standard way for an application to get limited, permission-based access to a service over HTTP without sharing the user’s password.

Instead of handing over credentials, OAuth 2.0 issues an access token. A token is a short-lived credential that represents the permissions the service approved (for example, “access calendar”). The application uses the token to call the service’s APIs, typically until the token expires, and in some implementations, until access is revoked.

Depending on the scenario, delegated access can be user-approved (an app acts on behalf of a user after consent) or service-to-service access (an app acts on its own behalf).

Why OAuth 2.0 matters for online security

OAuth 2.0 matters because it reduces the need to share long-term credentials with third-party applications. Instead of giving another app a password, access can be limited to what is needed for a specific integration, often granted through an approval/consent step for user-delegated access.

It also makes access easier to control over time. Tokens can be issued with limited lifetimes, and many implementations can revoke them without requiring a password change for the entire account. These controls are a part of why OAuth became a widely adopted pattern for modern API access.

How OAuth 2.0 works

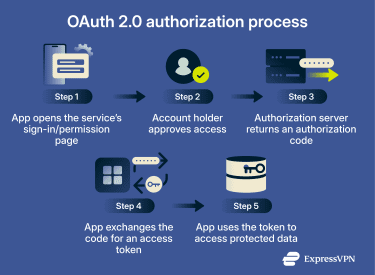

In most deployments, OAuth 2.0 follows a three-part pattern:

- An access decision is made, often through a user consent/approval step.

- A token is issued to represent that decision.

- The service’s API later accepts that token when protected resources are requested.

This standard flow helps keep integrations consistent across services and reduces the need for every third-party connection to invent its own access mechanism.

When things go wrong, it’s often due to implementation details, such as handling redirects safely, validating "state," storing tokens, or enforcing token checks, rather than in the overall design.

Core OAuth 2.0 roles

OAuth 2.0 defines four roles to clearly separate responsibilities. Most OAuth deployments involve these roles, and some may be fulfilled by the same system.

- Resource owner: The party that controls the protected data. This is often the account holder whose information or resources are being accessed.

- Client: The application requesting access. This can be a browser-based app, a mobile app, a backend service, or a command-line tool.

- Authorization server: The system responsible for verifying identity and approval, then issuing tokens when access is granted.

- Resource server: The API that hosts the protected resources and checks incoming tokens before responding.

Not every client can keep secrets. A confidential client is designed to protect its credentials because it runs in a controlled environment, such as a backend server. A public client runs on an end-user device or in a browser, where embedded values can be inspected or extracted, so it can’t reliably keep a client secret. This distinction affects how the client can authenticate and which OAuth 2.0 flow and safeguards are appropriate

OAuth 2.0 tokens and scopes

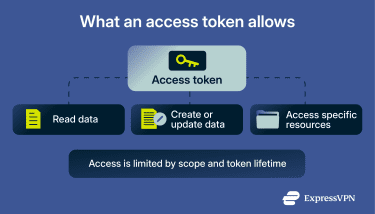

Tokens are the mechanism OAuth 2.0 uses to represent granted access. What a token allows and how long it remains valid depend on how it is issued and constrained.

Scopes work alongside tokens to define what an application is allowed to do. In practice, tokens and scopes are the main control layer for limiting third-party access. Many OAuth-related security problems often stem from weak token handling or overly broad scope choices.

Access tokens vs. refresh tokens

An access token is what a client presents to a resource server when requesting protected data. If the token is valid and includes the required permissions, the request is allowed. In most implementations, access tokens are short-lived to reduce the impact of exposure.

OAuth 2.0 does not require a specific access token format. Some systems use opaque tokens (random-looking strings) that the resource server typically validates by checking with the authorization server. Others use JSON Web Tokens (JWTs), a structured token format that includes claims (such as issuer, audience, and expiry) and can be validated locally by the resource server using cryptographic signatures. In both cases, the token functions like a credential: typically, whoever has it can use it.

A refresh token serves a different purpose. It allows a client to request a new access token when the current one expires, without having to repeat the full approval process. Refresh tokens are usually longer-lived and are only issued in certain flows and environments. Because refresh tokens are typically reusable until revoked or rotated, they can carry a higher risk if compromised. For that reason, many implementations restrict their use, rotate them after each exchange, or avoid issuing them to applications that can’t store them safely.

OAuth 2.0 scopes and permissions

Scopes are often how OAuth 2.0 limits access in practice. When an application requests authorization, it asks for one or more scopes that describe what it wants to do. The authorization server can approve all of them, some of them, or none at all, and the resulting token reflects that decision.

What matters is that scopes are enforced by the resource server, not just declared by the client. If a request attempts an action outside the approved scope, it should be rejected, even if the token itself is otherwise valid.

In real systems, scope design is a trade-off. Broad scopes are easier to manage but increase impact if a token is misused. Narrow scopes reduce exposure but can make integrations harder to maintain. Mature implementations aim for scopes that are specific enough to limit damage while remaining understandable and stable over time.

OAuth 2.0 grant types explained

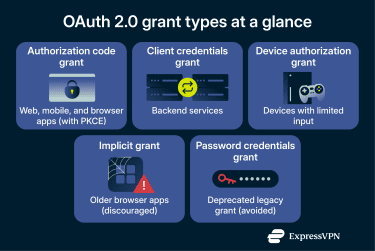

OAuth 2.0 supports multiple grant types (flows) because applications operate in different environments. Each grant defines how a client obtains tokens and what trust assumptions are made about the client and its runtime.

Choosing an inappropriate grant type can lead to OAuth security problems, especially when a flow is used in an environment for which it was not designed. Some grants target interactive sign-in and consent, others target service-to-service access or constrained devices. A few exist mainly for legacy compatibility and are generally not recommended for new implementations.

1. Authorization code grant

The authorization code grant is a common choice for many modern OAuth 2.0 applications. It separates approval from token issuance by returning a short-lived authorization code that the client exchanges for an access token via a direct request to the authorization server's token endpoint.

This design keeps access tokens out of redirects and browser history. Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE) adds a one-time verification step: the client generates a secret code verifier and sends a derived code challenge at the start, then proves it has the verifier when exchanging the authorization code for tokens.

This helps prevent an intercepted authorization code from being redeemed by someone else. This pattern is common in web and mobile integrations that redirect to a provider sign-in and consent screen.

2. Client credentials grant

The client credentials grant is used when a client application needs to access a resource on its own behalf rather than acting on behalf of an individual account. There is typically no user approval step because the token is issued outside the context of a resource owner.

This flow is common in service-to-service communication, such as internal APIs calling other services. The client authenticates directly with the authorization server using its own credentials and receives an access token scoped to the actions that the service is allowed to perform.

3. Device authorization grant

The device authorization grant is designed for devices that can’t easily complete a browser-based sign-in, either because they lack a browser or because input is too limited to type credentials comfortably.

Instead of signing in on the device itself, approval happens on a separate device with a browser. Meanwhile, the device polls the authorization server's token endpoint until approval is completed and an access token is issued.

This approach avoids embedding credentials in constrained environments while still using standard OAuth tokens. It’s common on smart TVs, game consoles, set-top boxes, and command-line tools.

4. Implicit grant

The implicit grant was introduced to support browser-based applications running as public clients, where a back-channel token exchange wasn’t practical. In this flow, the access token is returned directly in the redirect response.

This design exposes tokens to the browser and to front-channel transport, increasing the risk of leakage. For that reason, current guidance discourages the implicit grant in favor of the authorization code grant with PKCE.

The implicit grant remains part of OAuth 2.0 and still appears in older single-page applications, but it's generally avoided in new builds.

5. Resource owner password credentials grant

The resource owner password credentials grant allows a client to collect a username and password and exchange them directly for an access token. It assumes a high level of trust between the client and the resource owner.

This grant bypasses several OAuth protections and conflicts with modern security patterns such as multi-factor authentication (MFA) and external identity providers.

As a result, it’s generally not recommended and should be avoided in new systems. It’s mostly found in legacy integrations.

OAuth 2.1 direction

OAuth 2.1 is an in-progress effort to consolidate OAuth 2.0 and widely adopted security practices into a streamlined baseline. It reflects modern best practices by removing legacy flows, such as implicit and password grants, and by requiring protections, such as PKCE with the authorization code flow.

In practice, OAuth 2.1 narrows the set of recommended choices rather than introducing a new authorization model. The intent is to reduce configuration errors by standardizing on what is already considered the safer baseline.

OAuth 2.0 security risks and limitations

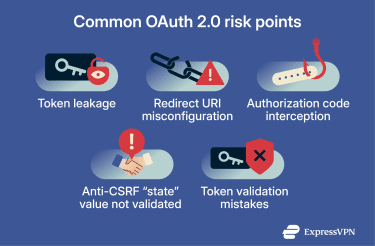

OAuth 2.0 is a flexible authorization framework, but its security depends heavily on implementation details. Many real-world OAuth incidents come from weak configuration, unsafe integration patterns, or incorrect assumptions about what tokens represent, rather than from a break in the core specification.

Because OAuth relies on tokens to represent access, small mistakes in how tokens are issued, handled, or checked can turn an otherwise sound design into an access leak.

Common OAuth 2.0 security risks

A common risk is token leakage. If an access token is exposed through logs, browser storage, referrer headers, or other unsafe handling, it can typically be reused by whoever obtains it. Since many OAuth deployments use bearer tokens, possession is often sufficient to exercise the token’s privileges.

Another frequent issue is the interception of authorization codes, often caused by weak redirect handling or missing protections for public clients. Redirect uniform resource identifiers (URIs) are the callback addresses that the authorization server sends the browser to after approval. They are a common failure point: safer implementations require redirect URIs to be pre-registered and matched exactly, rather than allowing broad patterns or user-controlled redirect values.

OAuth exchanges can also be vulnerable to cross-site request forgery (CSRF)-style attacks when the client can’t reliably tell whether an incoming authorization response belongs to the request it started.

The “state” value is a client-generated, hard-to-guess value sent with the initial authorization request and returned unchanged in the response. If the “state” is missing or not validated, an attacker can trick the client into accepting an authorization response it didn’t initiate, leading to the wrong account being linked or access being granted under the wrong context.

Token misuse and misconfiguration risks

Token-related failures are often caused by choices that “work” functionally but quietly increase exposure. Examples include issuing tokens with overly broad scopes, long lifetimes, or unclear constraints on where they can be accepted.

Refresh tokens can extend access beyond the lifetime of a single access token. If refresh token handling is weak (for example, weak storage controls or lax issuance rules), the impact of a compromise can be larger than that of an access token leak.

Why OAuth 2.0 must be implemented carefully

OAuth 2.0’s flexibility means insecure implementations can still be “spec-compliant.” Risk often accumulates through small decisions at the edges: relaxed redirect rules, legacy flows kept for compatibility, tokens accepted more broadly than intended, or incomplete validation of authorization responses.

More secure implementations align with current guidance and treat every step of the exchange as security-critical: strict redirect URI handling, request/response binding, appropriate flow selection for the client type, and consistent token validation and storage controls.

OAuth 2.0 vs. authentication standards

OAuth 2.0 is often mentioned alongside other standards for identity and access. That can be confusing because these systems solve related but different problems. Understanding the difference helps avoid designs that work in basic tests but fail under real security requirements.

OAuth 2.0 vs. OpenID Connect (OIDC)

OAuth 2.0 delegates access to protected resources (often via APIs). It defines how an application obtains and uses tokens to perform allowed actions, but it does not define a standardized way to deliver a verified user identity to the client.

OpenID Connect (OIDC) is an identity layer on top of OAuth 2.0. It adds a standardized sign-in flow and an ID token that carries identity claims and defined validation rules. In practice, OIDC is used for “sign in with” and single sign-on (SSO) experiences, while OAuth 2.0 is used to authorize API access. They are commonly used together but aren’t interchangeable.

OAuth 2.0 vs. SAML

Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) is an older, widely used standard for authentication in enterprise SSO. It lets one system (an organization’s identity provider) send a signed assertion to another system to confirm that an account has signed in. This is most commonly done through a browser-based redirect during login.

Compared with OAuth 2.0 and OIDC, SAML typically uses Extensible Markup Language (XML) documents to carry these signed assertions. This works well for established enterprise SSO and many internal applications, but it is less commonly used for modern API access patterns that rely on lightweight tokens.

OAuth 2.0 and SAML are sometimes used together. For example, SAML can handle the initial sign-in to a central enterprise portal (SSO), while OAuth 2.0 tokens are used to authorize access to specific downstream APIs and services after sign-in.

| Standard | Primary purpose | What it handles | Typical use cases |

| OAuth 2.0 | Authorization | Delegated access to APIs using tokens | Third-party integrations, API access delegation, scoped access without sharing passwords |

| OIDC | Authentication | Verified user identity on top of OAuth 2.0 | SSO, “sign in with” login flows for web and mobile apps |

| SAML | Authentication (enterprise SSO) | Federated identity assertions between trusted systems | Enterprise SSO, internal applications, legacy identity integrations |

Learn more: Find out how ExpressVPN authenticates its apps.

FAQ: Common questions about OAuth 2.0

What does OAuth stand for?

OAuth stands for “Open Authorization.” The name reflects its purpose: providing an open, standardized way to delegate access without sharing long-term credentials directly with another application.

Is OAuth 2.0 authentication or authorization?

Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0 is designed for authorization, not authentication. It determines whether an application is allowed to access certain resources, not who someone is. When identity verification is required, OAuth 2.0 is typically combined with OpenID Connect (OIDC), which adds a standardized authentication layer on top.

What is an example of Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0 in use?

A common example is a budgeting app connecting to a bank account to import transactions. The app doesn’t collect the bank password. Instead, the bank (or its authorization service) shows a sign-in and approval screen, and after approval, the app receives an access token. The app then uses that token to retrieve only the data it was granted access to, such as read-only transaction history.

How does OAuth 2.0 work with REST APIs?

Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0 is often used to protect Representational State Transfer (REST) APIs, a common style of web API where clients access resources using standard HTTP methods such as GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE. With OAuth 2.0, the client includes an access token with each API request. The API checks that the token is valid and that it authorizes the requested action (for example, based on scope) before returning data.

This can support a stateless design because each request contains the authorization information the server needs, rather than relying on a user session cookie that must be stored and retrieved between requests.

How do refresh tokens work in Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0?

Refresh tokens allow a client to obtain new access tokens after the original token expires, without repeating the full approval flow. They are often issued only when they can be stored securely and handled more carefully than access tokens, since they can be reused. Many modern implementations rotate OAuth 2.0 refresh tokens or restrict their use to limit the impact of compromise.

Is Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0 secure?

OAuth 2.0 is considered secure when implemented in accordance with current guidance. It reduces password sharing and supports limited, revocable access through tokens. Most security issues stem from misconfiguration, outdated flows, or unsafe token handling rather than flaws in the core framework.

Is Open Authorization (OAuth) 2.0 a protocol or a framework?

OAuth 2.0 is best described as an authorization framework. The specification defines roles, authorization flows, and how access tokens are issued and used, but it deliberately leaves many implementation details open. This flexibility allows OAuth 2.0 to work across different application types and environments, but it also means security outcomes depend heavily on implementation choices rather than on rigid protocol rules alone.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN